Hyperion Plant Hoping to Revamp Its Image Through Tours for Public

- Share via

As she was being escorted down the back streets of the Hyperion Sewage Treatment Plant one day last week, eighth-grader Bella Heerasingh blurted out the question that seemed to be on the minds of many of her classmates.

“If you stay here too long, can you get sick from the smell?” the 13-year-old asked tour guide MaryAnne Pierson.

Pierson did not have an answer, but she promised Heerasingh and the other Culver City Middle School students that before their tour of the sprawling plant was over, they would learn a lot of things about the complex world of sewage treatment.

The tour was a trial run of sorts for Pierson, who was recently hired to put together a program that will offer regularly scheduled public tours of the facility, the largest of the four waste-water treatment plants operated by the city of Los Angeles.

‘Shrouded in Mystery’

In January, Pierson, 35, said, she will hire six part-time guides to conduct tours as part of an effort aimed at making the plant’s inner workings more understandable to the people and communities it serves.

“Hyperion is not going to move or disappear, and we would like our neighbors to know what’s going on around here,” Pierson said. “Hyperion has always been shrouded in mystery.”

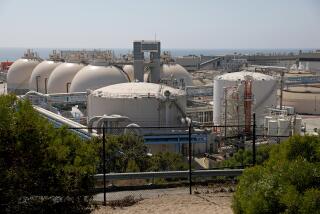

Harry Sizemore, Hyperion’s manager, said that in the past, volunteers or employees such as himself gave public tours of the plant, which on an average day treats more than 400 million gallons of waste water.

But those tours were halted in 1982 because there were not enough people available to conduct them, Sizemore said. Since that time, occasional tours have been arranged for small groups and individuals.

Unlike the tours given before 1982, those that will begin next year will be geared more toward the general public rather than professionals or environmentalist groups that have a special interest in what is going on at the plant, Pierson said.

The tour guides will be given at least six weeks of training, and the plant will advertise to ensure that people know about the tours, she said. So far, 35 people--ranging from retired teachers to students--have applied for the six part-time jobs that will pay about $6 an hour.

Anna Sklar, spokeswoman for the city’s Bureau of Sanitation, which runs Hyperion, conceded that the plant lacks “glitzy exhibits”--unless you count the 6-inch mantis shrimp that was plucked from the Santa Monica Bay some time ago by staff biologists. Some Hyperion workers consider the crustacean, which has a vicious nature, to be the plant’s unofficial pet.

Pierson acknowledges that some people do not think very highly of the plant, which employs about 900 people. “I would say there is a certain image in the public’s mind that any pollution in the ocean is Hyperion’s,” she said.

Nevertheless, Pierson predicted that the tour guides will be kept busy. People are continually telephoning her to ask if the plant conducts tours. “I have people calling me every day, every week,” she said.

That was how the Culver City students wound up at the plant. Science teacher Larry Falk said he inquired about taking the students on a tour of the plant as a way to conclude a 3-week lesson on pollution.

Not that a field trip to Hyperion was greeted by wild applause from the students. “Their first reaction was ‘Oh, that stuff stinks,’ ” Falk said.

On Wednesday, Pierson first gave the students a brief lecture about the plant before giving them hard hats and marching them over to the plant’s old main power building, which is slated to be torn down in three years.

From the top of the building, students were given an overview of the plant and the various construction projects now under way to upgrade and expand it. At least six separate projects are in varying stages of completion.

The students were then taken by van to the plant’s control room. There, operator Harry Khachadrian, an amiable man, attempted to explain various plant operations to the students. Behind him on the wall was a flow chart with phrases such as “closed loop cooling water system” and “sludge digestion and co-generation system” printed on it.

After the control room, the students visited the plant’s laboratory, where scientists talked about how they gather water and marine life samples, bring them back to the lab and examine them so pollution levels can be monitored.

“It’s good that they are thinking about the water,” Carlos Herrera said as he walked out of the laboratory.

Several other students echoed Herrera’s view. But Phillip Carter said that he was not sure what he learned from the field trip. He did, however, offer an opinion about the plant’s overall operation.

“I just think it is too extravagant to have this big, big facility,” said the 13-year-old, who had a Bush-Quayle campaign button pinned to his jacket.

Kevin de Toledo, 14, came away from the field trip scratching his head. “I couldn’t understand what they were talking about,” he said, referring to his visit to the plant’s control room.

Pierson acknowledged that some of the tour was probably a bit too technical for many to understand. But the tour was practice for those that will follow, which the new tour guides will conduct. Pierson said she hopes they will help people understand what Hyperion does.

After all, Pierson noted, “as long as there are human beings, we’re going to have waste water.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.