Celebrate George Washington, Not for the Cherry Tree Tale But as a Man of Character

- Share via

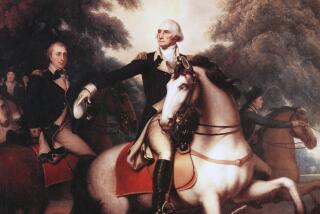

This week marks the 257th anniversary of George Washington’s birth, this year the bicentennial of his inauguration as President.

If the thousands of volumes written about Washington were laid end to end, even that legendary hurler probably could not throw a silver dollar across them. Yet we do not know the man. We have relegated him to tales of hatchets and cherry trees, to antiquarian shrines and February sale ads. He is little more than a purse-lipped visage on our money. By trivializing him, we miss the lessons he could teach us.

We imagine Washington to have been aloof and stiff. In fact, he was a man of personal charm and physical grace. These attributes contributed to the majestic presence that his contemporaries found so impressive. “His person,” said Thomas Jefferson, “was fine, his stature exactly what one would wish, his deportment easy, erect and noble. . . .”

The Revolutionary War generation feared charismatic figures who could play upon the passions of the people in order to make themselves dictators. Washington’s dignified and reserved demeanor helped to assure them that they could trust him with power.

The impression Washington made was no accident. He consciously cultivated a style that fit the ideals and fears of his contemporaries. He deliberately set out to persuade them of his trustworthiness. In doing so, he displayed his genius as a political actor. He was not a hypocritical manipulator or a mere image created by media handlers. He and his contemporaries believed that a leader’s exterior manner should reflect his interior character.

Ten days after his appointment as commander of the Continental Army, Washington demonstrated the linkage between his skill at political symbolism and his trustworthiness. Many Americans feared abuses of military power. History was filled with examples of popular military leaders who had become tyrants. New York’s revolutionary legislature praised the general’s ability and virtue, but then registered its concern “that whenever this important Contest shall be decided . . . You will chearfully resign the important Deposit committed into Your Hands, and reassume the Character of our worthiest Citizen.”

Washington tailored his reply to allay the fear of military despotism. On behalf of his fellow generals, he wrote: “When we assumed the Soldier, we did not lay aside the Citizen, & we shall most sincerely rejoice with you in that happy Hour, when the establishment of American Liberty . . . shall enable us to return to our private Stations. . . .”

This statement was not just shrewd public relations. It set the tone for all of Washington’s future public service. “His was the singular destiny and merit,” said Jefferson, “of scrupulously obeying the laws through the whole of his career, civil and military, of which the history of the world furnishes no other example.” Washington’s consistent submission to civilian authority and the laws helped establish an American tradition of civilian control of the military and constitutional restraints on the use of power. Thus have we been spared the tragic betrayal of our revolution, so often suffered by other nations.

George Washington deserves our gratitude for his sense of civic duty, but the achievement was not his alone. His fellow citizens made it unmistakably clear what they required of him. Obedience to legal limits and subordination to elected leaders would win him lasting fame. Abuse of the powers granted him would bring down everlasting execrations.

Some of us today naively excuse lawless abuses by soldiers and presidential advisers and Presidents because they were promoting policies that we favor. Others cynically dismiss such misconduct because “they all do it.”

Washington and the revolutionary generation would have found our attitudes antithetical to the kind of government and public morality they demanded of one another and labored to hand down to us. They would never have considered Richard M. Nixon an elder statesman or Oliver L. North a national hero. When we laud such men or allow them to profit by their violation of the public trust, when we fail to hold our leaders to the standard of George Washington and his generation, we betray our civic inheritance. Worse, we betray ourselves.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.