Keeping Employees Happy : Sportswear Firm Beefs Up Benefits to Boost Worker Contentment

- Share via

VENTURA — Being nice is just good business at sportswear maker Patagonia, where keeping workers happy is so important that an occasional “surf break” can replace the traditional coffee break.

The brainchild of business rebel Yvon Chouinard, Patagonia broke ground in the 1970s by thumbing its nose at fashion standards with an emphasis on function over style, as well as by nurturing employee contentment.

Patagonia is part of a national trend that finds many companies beefing up benefits to recruit and retain employees.

Patagonia’s status as an industry rebel changed as its sturdy, brightly colored clothing became trendy and its corporate generosity helped turn the once-tiny venture into a multimillion-dollar international enterprise.

Its most prominent customer is President George Bush, who recently appeared on the cover of People magazine and was pictured in a two-page spread in Sports Illustrated wearing a Patagonia jacket.

The company’s customers range from Himalayan climbers and white-water kayakers to weekend campers and patrician horseshoe players like Bush.

Another prominent customer is the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, which outfits space shuttle astronauts in long underwear made of Patagonia’s trademarked Capilene material, company spokeswoman Karen Frishman said.

Business Beginnings

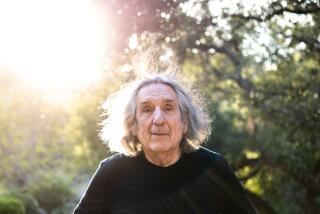

Chouinard, who entered business selling hand-forged mountain-climbing gear from the back of his pickup truck, has created such a nurturing and productive work environment that competitors routinely try to lure Patagonia workers away, he said.

“You get out of benefits what you put into them,” said Chouinard, 50, who founded the company on the Southern California coast to be close to its surfing beaches.

“We have more benefits than just about any company around, and it pays off in terms of production.”

Perks include an on-site day-care center and school for children ranging in age from 8 weeks to 14 years, generous parental and health benefits, employee recognition programs, subsidized wilderness adventures and employee prices on company clothing 10% below wholesale.

“The day-care center is a profit center in my mind,” Chouinard said. “It keeps five to 10 people a year from having to quit. That saves us a lot of money.”

Chouinard, who owns Patagonia’s parent company, Lost Arrow Corp., outright, said it costs him up to $50,000 to bring a new worker to peak efficiency. Pay ranges from about $6 an hour for entry-level warehouse workers to between $50,000 and $100,000 for middle managers, he said.

Paid Maternity Leave

Working mothers, who get two months paid maternity leave, rave about the day-care center.

“All three of my kids are here at some point in the day, so I am able to keep close tabs on them,” said accountant Pat Haycox, whose youngsters range in age from 3 to 9. “They’re much more relaxed being close by and I’m more relaxed too.”

“It’s great,” said new mother Dee-dee Locey, the company’s payroll administrator who brings her 6-month-old daughter to the infant-care center. “I’m still nursing my baby, so I can keep on nursing and I don’t have any anxieties about being away from her because she’s right here at work.”

Women represent 60% of Patagonia’s 450-member work force, a percentage that extends to upper management, making the state-licensed child-care facilities especially attractive benefits, administrative director Pam Murphy said.

Employees are free to leave their desks and visit the children, and youngsters can use telephones to call working parents for a kind word.

“They know that if they really need mom, she’s there,” said Anita Garaway, child-care coordinator. “Our kids consistently test higher than average when they leave for public school because what it all boils down to is that they feel good about themselves.”

The day-care center and after-school programs serve about 80 youngsters, 87% of whom are the children of company employees, Garaway said.

Director of human resources Susan Greene, sweaty and still wearing a leotard and T-shirt after lunch-hour exercise, said having the day-care center nearby can also be a comfort to childless workers like her.

“If you’re having a bad day you can go down and finger-paint in chocolate pudding with the kids,” Greene said.

Patagonia encourages lunch-time exercise and allows occasional surf breaks as part of the company’s focus on preventive measures to reduce major health claims, Frishman said.

Company headquarters feature a sand volleyball court, showers and an inexpensive cafeteria offering a variety of health food.

A morning aerobics exercise class runs on company premises and overweight workers can take part in an on-site Weight Watchers class.

Another benefit is “flex-time” scheduling, allowing workers like two avid mountain climbers to fill the same position during alternating three-month periods of the year.

Other Firms Taking Notice

Other companies are recognizing the value of cultivating worker happiness, said Laraine Engel, research manager for the Merchants and Manufacturers Assn.

“They know they have to do something to keep good people around,” Engel said, adding that medical benefits rose 33% nationwide in 1987 and 22% in 1988.

Representing Lost Arrow’s hiring priorities is chief executive officer Patrick O’Donnell, whose mountaineering resume, which includes a conquest of 23,400-foot Nun Kun in India, is matched by professional exploits that include founding the Kirkwood ski area near Lake Tahoe.

The company is a successful mix of retail, mail-order and wholesale ventures, serving hundreds of wholesale customers while operating eight retail stores, including one in Chamonix, France.

Its irreverent catalogue features tongue-in-cheek photos like one showing a man modeling a sports coat while covered head to toe in a blanket of dripping mud.

Lost Arrow’s worth is a poorly kept secret because although sales figures are not made public, it has a well-publicized program of donating 10% of its profits each year to organizations ranging from the United Way to the environmentally oriented Surfrider Foundation.

Donations to more than 200 groups amounted to more than $500,000 in 1988 and are expected to near $1 million in 1989, according to company literature.

Despite its success, Patagonia isn’t ready to stop trying to keep workers happy.

“We’re looking for new ways to move into the ‘90s,” Murphy said. “We’re seeing the worker pool diminishing, so we can’t be static. What exists today might not be enough five years from now.”