CHINA : Sichuan Province, largest in China offers vast valleys, raging rivers, huge mountains and a plateau that stretches to the Himalayas.

- Share via

HENGDU, China — I knelt down beside fried dough twists, jasmine tea and a bowl of candies. The Tibetans watched me closely. As instructed, I used my thumbnail to scoop yak butter from the oiled wood tub and drop the yellow, waxy gobs into my tea.

Yak butter tea is a staple for Tibetan nomads and an honor for distinguished guests.

I did not consider myself distinguished, just one of the first foreigners to visit the Tibetan Highlands area of China in almost 25 years.

Boojum Expeditions of San Diego had negotiated for two years to get permission from the People’s Republic of China to explore northwestern Sichuan Province on horseback. I was one of the 13 Americans who took part in the journey last summer.

Sichuan is the largest of China’s 18 provinces, 40% larger than California, with a population of almost 100 million. Only in the most remote areas are you free of the crowds.

The mid-China province is subdivided by vast valleys, monsoon-swollen rivers and mountains soaring to 22,000 feet.

The western third of Sichuan consists of the 12,000-foot-high Tibetan plateau, which stretches to the Himalayas, about 750 miles. The only way to get here is by a dusty and pulverizing two-day bus ride from the provincial capital of Chengdu.

The fact that our trip was detoured only once because of a landslide was remarkable. Landslides are commonplace. More than once we followed a bulldozer as it pushed boulders from the treacherous roads.

The beauty of the highlands alone is worth the trip. The grasslands look like a wildflower carpet of pink daisies, red poppies, buttercups and purple violets.

Eagles, hawks and ravens circle the hillsides. We saw several of the rare and elegant black-necked cranes, the official bird of China.

The lush pastures are dotted with grazing sheep and yaks. The latter are herded by the nomadic Tibetans and used for transportation, shelter and food.

The thin air at these high elevations is no problem for the yaks--or the Tibetans--but we foreigners felt every 15,000-foot pass squeeze the breath from our lungs and the blood from our heads.

Although the Sichuan highlands are primarily Tibetan in culture, they are governed by the Chinese. But the cultural tensions are not as apparent here as they are in the Tibetan autonomous region and its capital, Lhasa.

The grassland towns, where trade brings sidewalk merchants and shoppers together, bustle with a cacophony of sounds.

Beginning at 7 a.m., propaganda blares over the loudspeakers with local and Beijing news and popular military marching songs such as “The East Is Red.”

Worn pool tables are wheeled into town by people who charge a nominal fee for their use.

Eventually I got used to the Chinese drivers’ love of honking their horns. By comparison, Manhattan cab drivers seem patient.

We gathered curious crowds each time we bargained for ethnic art, Tibetan knives, riding boots and food.

As part of our 24-day trip we went on a 250-mile horseback expedition. For 12 days we rode spirited ponies supplied by our four Tibetan “wranglers.” We camped in pop-up tents and ate a variety of food from Chinese noodles to peanut butter and canned sausage.

During the trip the most courageous males bathed in the swift, mud-colored rivers, but everyone else went without a bath for two weeks.

While riding and camping with the wranglers we were able to get a glimpse of the 1,200-year-old Tibetan culture.

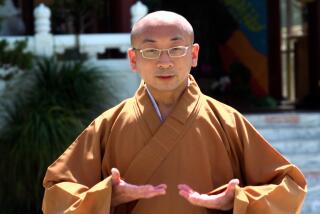

A respect for religion and spirituality was apparent wherever we rode. Majestic monasteries, temples smoldering with incense, moaning ceremonial trumpets and monks in flowing robes create a mystic aura around almost every village.

Prayer wheels, from hand-held to two-story models, continually generate invocations to Buddha. Gargoyles, swastikas and gold-skinned Buddhas reinforce the power of the Tibetans’ spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama.

Tibetans are famous for their skill on horseback. We saw them gallop past, sometimes with saddle and bridle, sometimes bareback. One hot and cloudless day we even saw a young man herding yaks across a muddy river with nothing on the horse . . . or on himself.

At sunset one evening the sound of a faint bell drew me away from our campsite. In the distance a weathered shack stood guard over a water channel. A small paddle-wheel churned beneath the floor. The faint sound I heard was a spinning prayer wheel inside the shack, striking a tiny bell. Each “ting” was a message to Buddha.

When a smiling Tibetan rode up on a white palomino and gently patted his horse’s rump, offering me a ride, I thanked Buddha for my luck. The rider wore wooden prayer beads around his neck and a broad smile glowing with gold-capped teeth. He had visited our encampment and wanted to take home a foreigner to dinner.

The Boojum Expeditions’ brochure cautions: “Traveling to remote areas in China is physically and psychologically demanding. Accommodations and facilities can be very rustic. In most cases you must carry your own luggage, and daily showers are the exception--not the rule. The most important thing to pack is a smile and the willingness to try everything.”

I kept these words in mind as the rider, whose name was Gharrang, led me past the “doorbell, burglar alarm and pet” of all Tibetan nomads: his family’s rabid-sounding mastiff guard dog.

Inside the small wood-and-sod home, Gharrang took me down a narrow hall that smelled of fresh-cut pine and smoke. On the walls in the cavernous back room were images of Buddha and the Dalai Lama.

The holy images were adorned with cloth scraps, trinkets and yak butter candles. In the middle of the room hung a tiny banner attached to a prayer wheel in the rafters. Anyone passing by could yank a quick prayer.

Gharrang told me that he had been a Lamaist monk for 15 years, but that his spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, had been in exile in India since 1959 when the Chinese government took control of Tibet. Gharrang showed me his faded and much-folded photocopy of a newspaper picture of the Dalai Lama.

During the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966-76), the Red Guards had destroyed the local monastery. Gharrang’s scriptures were burned, and he was sent home with orders to marry.

Lamaism is undergoing a revival. Burned and dismantled temples, desecrated stupas (prayer towers) and abandoned monasteries were being rebuilt in every town we rode through. Campaign buttons with the Dalai Lama’s picture are everywhere. Gharrang’s crimson-cheeked daughter is a 17-year-old Lamaist nun, complete with draping maroon-colored robes.

Where was the rest of Gharrang’s family? He said his wife, father and two sons were camped in yak-hide tents in the next mountain range, tending the family’s yak and sheep herds for the summer.

In Gharrang’s living room his molded-clay fireplace had cooking portals but no chimney. Baking near the tin teapot were delicate mud renditions of Buddha, reminiscent of Christmas cookies.

The other half of the room was raised about 18 inches to allow fireplace air to warm the floor during the bitter-cold winters.

The golden twilight heightened the fine wood carvings and the collection of pastel-colored Buddha posters adorning the walls. Gharrang considers this home his temple.

He set a worn wooden box at my feet. It contained three compartments: barley flour, crystallized yak cheese called churra, and dried and salted yak jerky. He put three big scoops of ground barley from the box into my bowl of tea, added two scoops of brown sugar and two more of rancid-smelling yak butter.

Then he kneaded the concoction into a lump that he called tsampa --a mainstay of the Tibetan diet. The consistency was somewhere between Silly Putty and cookie dough. It was sweet and rich, and very filling.

Next came maotai (sorghum or rice liquor). Raising his thimble-size glass, Gharrang dipped his forefinger into the syrupy-clear booze and ceremoniously flicked the droplets into the air above his head three times. “To the sky, the wind and the land,” he said.

The maotai drink tasted like concentrated rose-petal perfume. Later, when Gharrang was asked about the ritual, he dismissed the pagan blessing as “just a superstition.”

After thanking Gharrang for his hospitality, I presented my bandanna as a parting gift. He bowed repeatedly to me in appreciation and stowed the gift in the special cabinet where he kept his Dalai Lama clipping.

As we left, Gharrang gave me a blessed swatch of cheesecloth to offer Buddha at the next Lamaist temple I visited. In Tibetan custom, this gesture is an honor and ensures safe travel.

Pulsing Prayer Bell

It was nightfall by the time Gharrang and I rode back to the distant Boojum Expeditions campfire. We swayed on the back of his horse in the cool air. When we passed the prayer bell that I had explored earlier, we each sang a song into the wind.

Gharrang’s song was chanted, almost wailed, a free-form and poignant ballad. His voice echoed the beauty, mystery and sadness of this land and of the Tibetan people.

Adventure travel in China, by horseback or bicycle, is still the specialty of few tour companies. Trips are generally from 13 to 28 days, and prices about $150 U.S. a day. Most amenities are included, except air fare.

Boojum offers 23-day expeditions, $3,000 to $3,500 (not including air fare). Trips are by horseback or mountain bike, and are seasonal--from June to September.

The horse trip in the Tibetan Highlands is set for Aug. 1-23. Other horseback trips are to Inner Mongolia (July 8-30) and the Altai Mountains (Aug. 20 to Sept. 6) in China’s Xinjiang Province. A mountain-bike excursion is offered in the Highlands from June 28 to July 20.

Many airlines, including United, Northwest, Singapore and Canadian, offer daily service to Hong Kong. From there, entry to China is straightforward. Those airlines also fly into Beijing. Costs vary, but figure at least $1,000 round trip from Los Angeles to Hong Kong, $1,200 for Beijing.

Air fares within China are still reasonable on the country’s only airline, Air China, which until recently was known as the Civil Aviation Authority of China (CAAC). From Kong Hong to the capital of Sichuan Province, Chengdu, a direct nonstop flight is $180. From Hong Kong to Beijing the price is about $280.

China International Travel Service is the government’s company for single or group travel arrangements. It is knowledgeable and well-connected, but it will take you only where you have permission to travel. And its rates are high.

Individual travel in China is difficult to arrange without an interpreter or Chinese language skills. And only the most intrepid backpackers/bicyclists will appreciate the stunning sites and culture after the exhaustion and hassles of unescorted traveling.

For any trip to the Tibetan Highlands, be sure to pack lightweight gear for the rain, shorts for the humidity, and sunscreen and warm clothing for high altitudes.

The most important things to pack, however, are a smile and an open mind, as the expedition brochure says.

Adventure companies:

Boojum Expeditions: 2625 Garnet Ave., San Diego 92109, (619) 581-3301.

Odyssey Tours: 1821 Wilshire Blvd., Santa Monica 90403, (213) 453-1042.

China Passage: 168 State St., Teaneck, N.J. 07666, (201) 837-1400.

Sobek Adventures: Angels Camp, Calif. 95222, (209) 736-4524.

Wilderness Travel: 801 Allston Way, Berkeley 94701, (415) 548-0420.

China/Tibetan information:

China Exploration and Research Society: 4028 Chaney Trail, Altadena, Calif. 91001, (818) 791-5339.

China Books and Periodicals: 2929 24th St., San Francisco 94110, (415) 282-2994.

Snowlion Publications: P.O. Box 6483 Ithaca, N.Y. 14851, (607) 273-8506.

For more information on travel to China, contact the China National Tourist Office, 333 W. Broadway, Suite 201, Glendale 91204, (818) 545-7505.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.