The Legacy of Timur the Great : LACMA’s remarkable exhibition testifies to the urbane refinement of art under the conqueror Tamerlane

- Share via

Devout followers of art do a good bit of grumping these days about the ways their sacred objects are being used . Junk bond traders use art to gain cultural prestige. Corporations finance luster-lending exhibitions. Right-wing legislators threaten to sanitize the National Endowment for the Arts. Art, in short, is being transformed from a garden of cultural insight into a political plow.

A remarkable exhibition opening today at the County Museum of Art proves--if it is any comfort--that this is not the first time art has been put to work to tart up someone’s reputation.

The exhibition, on view to Nov. 15, is called “Timur and the Princely Vision” and concerns Persian art and culture in the 15th Century.

Exhibitions about the Middle East tend to get Westerners balled up on account of current hostility and ignorance, plus real historical complications, all compounded by changes in scholarly convention. The lands that used to be known as Persia are now roughly encompassed by Iran. The tyrant here called Timur might be more readily recognized by his old occidental handle: Tamerlane the Great, or sometimes Tamerlane the Lame.

Oh, him. Sure, I knew it all the time. He was the most awesome conqueror of the Middle East after his own hero Genghis Khan.

Timur--born in 1336--came roaring out of Transoxonia with his Turco-Mongolian hordes pillaging and plundering until he controlled an empire that gobbled up all of what is now Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq and chunks of India, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, China and the U.S.S.R.

Timur used terror systematically. One favorite trick was to mass the skulls of thousands of victims into huge columns outside the gates of cities he wished to impress.

Decidedly not a nice guy, but a charismatic leader capable of unifying factions and a shrewd politician who used the arts to impress the rubes, mollify the opposition and, naturally, glorify his glorious self.

This cultural manipulation is what the exhibition is all about, and it is a first. Put together by LACMA curator Thomas Lentz and Glenn D. Lowry, curator at the Freer and Sackler Galleries in Washington D.C., it is an understated triumph of organization.

Anyone expecting to be bowled over by gallons of gold and cornucopias of precious stones as they walk into the exhibition should be forewarned. In the first place, the most grandiose Timurid art is its architectural monuments such as the sanctuary dome of the masjid-i jami of Timur in Samarqand, which can be shown only in photographic murals. In the second place, this is one of those revelatory pieces of scholarship whose very fine catalogue is a virtual must for getting the best from the show.

The exhibition includes stunning objects such as Chinese-style jade cups and sections of architectural mosaics, but the largest number of works are drawings, calligraphic sheets and illustrated manuscripts that include some of the greatest known examples. Artistic pleasure here comes from such rarefied masterpieces as a bookbinding as delicate as lace where silhouettes of plants and animals have been cut from a single piece of leather. That’s just a trick, of course, as is the calligraphic page where microscopic arabesques are individually cut from paper. What makes them work is an exquisite sense of refinement that turns work after work into delicate visual poetry akin to patterns in a kaleidoscope.

Such attenuated elegance did not represent Timur’s personal taste, which tended to run to powerful candlesticks the size of cannon and Koran pages as big as pup tents. One hapless artist made Timur the Islamic version of the New Testament engraved on the head of a pin and he drummed the poor chap out of court. Who needs this little-bitty stuff? We need something huge to awe the plebes. The Trump Mosque.

There were buildings aplenty and luckily Timur’s vision was better than his taste. He needed the fealty of his Islamic subjects and so incorporated their literature, poetry and beliefs. He established Kitabkhana --royal libraries or workshops that became the centers of art, literature and learning. (Many a Timurid noble paid pious patronage and lip service to Islam while violating most of its codes in private.)

Timur introduced elaborate ritual codes into courtly ceremonies all designed to enhance his own awesomeness. Court etiquette was so complex that visitors had to be manhandled through the ceremonies to make sure they groveled correctly. This sense of convoluted correctness comes across in an art so intensely stylized it is a wonder it is often as fine as it is.

Timur died in 1405 at age 69. Without his leadership the empire came unglued, potential successors scrapping bloodily. When the dust settled the emergent leader was called Shahrukh. Until 1447 he ruled over an empire that was as fragmented within as it was opulent without.

Slowly the empire eroded into the kind of dalliance that is bad for politics and terrific for art. Manuscript illuminations and scalpel-sharp drawings tell the story in their style. They depict a world of disembodied pleasure where concubines loll in patterned rose gardens while the prince hunts, composes poetry, studies the Koran or consults his astrologer. (The stars were taken seriously. One prince drank himself to death after receiving a bad horoscope.)

The pictures may seem unreal but they are the precise metaphor of the reigning ideal of the princely world--separate, private and luxurious. As time wore on, cultural refinement held such sway that reputations were made and broken with literary quips and elaborate word games. During one of these literary jousts a noted social arbiter and wit became simultaneously annoyed at a door that was banging in the wind and another guest who was just as noisy. The wit asked someone to bolt the door. When the man rose to comply the wit said, “I meant to bolt it from the other side.”

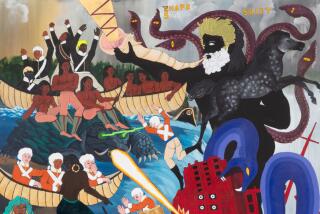

There is a kind of predictability to histories of crumbling empires. As the Timurids lost yet more power they had to cultivate the good will of religious men, and we see a series of paintings of bedizened nobles visiting hermit monks. As things got even more out of hand there was a Reagan-style revival of The Good Old Days where Timur is depicted as the great hero--the George Washington of his day, strong and wise. The paintings are as magnificent as their motive impulse is sentimental.

By the time the ferocious Uzbeks became belligerent in 1507, former Timurid boldness had given way to refinement. The empire was done for. Or was it? Timur’s manipulative and eclectic artistic program turned out to be his greatest legacy. It set a standard for urbane refinement that held sway through four Turkish dynasties from the Uzbeks to the Mughals. Timurid aesthetics were so widespread that they mark one of the world’s most fabled palaces. We think of the Taj Mahal as quintessentially Indian. As the show’s curators whisper enticingly: “Hey, folks, the Taj Mahal is a Timurid-style building.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.