Shattered Dream : Youngest Boy of Family From Nepal Shot to Death in Inglewood Robbery

- Share via

Matshyendra and Mathura Singh led a life of comfort and some position in their native Nepal. Surrounded by family and friends, the couple lived on the pension earned by Matshyendra after 28 years as an accountant for the U.S. Agency for International Development.

The Singhs said they never would have considered leaving their home in the capital city of Katmandu, in the shadow of the Himalayas, were it not for their son Majendra.

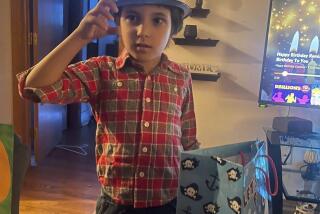

The teen-ager, the youngest of three children, was bright and outgoing. His parents wanted him to have an American college education so he could pursue his dream of becoming an architect or engineer. So, 21 months ago, the family moved halfway around the world to settle near relatives in Inglewood.

Matshyendra remembers that decision with sorrow.

“I thought, ‘I will see him established here, then I will go home,’ ” he said.

But last week the aspirations of a family and much of the tightknit Nepalese community in Los Angeles were shattered when Majendra Singh--son of Nepal and child of the American Dream--was shot to death in his new hometown.

Majendra, 19, was counting the night’s receipts at the Pizza Hut on Manchester Avenue when he was confronted by two men. They shot him and took the money.

Majendra will be cremated Saturday in the Hindu tradition, his father said, freeing the young man’s soul to ascend to heaven. The weight of the tragedy remains with the living.

Tuesday, in the middle of a 10-day mourning period, the father sat cross-legged on the floor of the family’s modest apartment, his voice barely audible above the roar of jets from nearby Los Angeles International Airport.

Matshyendra, 50, said he had planned to remain here until his children were established.

“Now my son is gone forever and I feel my purpose is completely lost.”

The grief is shared by Southern California’s Nepalese community. The 300-member American Nepal Society was to meet in two weeks to celebrate Dashin, the festival that is the holiest event on the Hindu calendar. Instead, the gathering will be used to remember and pray for Majendra, said Naren Suwal, a member of the society and relative of the Singh family.

The Singhs have rejected the help of grief counselors and victim assistance programs.

“We have a different way,” said Suwal, who calls Matshyendra a “brother-cousin”--their grandfathers were brothers.

A stream of friends and relatives came to the family’s home on Crenshaw Boulevard throughout the week, bringing food and prayers. And the American Nepal Society has established a memorial fund.

Majendra will be cremated Saturday at Forest Lawn Mortuary in Pomona, along with his jata , the astrological chart that is drawn at birth for Hindus.

On Majendra’s last birthday in Katmandu, his mother had gone to an astrologer with her son’s jata. “The woman said ‘The stars are not very cooperative,’ ” his father recalled, “but she said ‘There is nothing major to fear.’ ”

From the time the family arrived in Inglewood, however, their stars seemed to be crossed. They came to Inglewood to live near Suwal, who had a budding career in hotel management after immigrating several years earlier.

Matshyendra’s $200 monthly pension had supported the family in Nepal, one of the world’s poorest nations, but it was paltry by American standards. Half of the $3,500 he brought from his homeland had to be spent for a deposit on an apartment.

Matshyendra wanted to start working immediately, so he could send his son to college. But for months he could not find a job. Employers told him alternately that he did not know computers, or that he was overqualified.

Majendra and his sister Sunayana, now 21, were forced to find jobs to support the family. Their educations would have to wait.

Sunayana worked part time at McDonald’s.

Their mother, who speaks little English, cared for the children of other Nepalese families.

A few weeks after they arrived in January, 1988, Majendra was working at Pizza Hut about a mile north of his home. He earned minimum wage, but he could work long hours and he was promoted quickly from dishwasher to cook, to night crew chief. His pay went up to $5 an hour, and he often worked 60 hours a week.

“I used to ask him, ‘Are you tired, Majendra? Are you tired?’ “recalled Juana Flores, the youth’s co-worker and friend. “And he said, ‘No, you can’t get tired in this kind of job.’ ”

Friends explained that for Hindus, work is a form of worship.

His father waited up late every night until his son came home. He counseled Majendra to work fewer hours and to start classes at a community college. But Majendra demurred, saying that his family came before his education.

Majendra tried to talk his father out of taking a job as a stock clerk at a Torrance liquor store, saying it was too demeaning for a professional man. But Matshyendra took the job anyway and, because of the extra income, his son felt free this fall to enroll at El Camino College in Torrance.

There, he took two courses to get acclimated. Next semester, he hoped to enroll full time.

“He always wanted to become somebody,” Suwal said.

Majendra continued to work long hours. A recent pay stub showed that he logged 112 hours in two weeks. Often, he closed the pizza parlor and counted the receipts.

Suwal, 34, who had been robbed while managing a hotel in Covina, told Majendra that if bandits ever came, he should give up the money.

After another long Friday night, Majendra closed the restaurant at 1 a.m. last Saturday morning. It was just before 2 a.m. that two young robbers confronted him.

None of the three other employees who were cleaning up that night know how the thieves got into the restaurant, police said. Majendra did not resist them, but was shot dead, a woman who worked behind the counter told police.

Matshyendra Singh can almost understand the robbery, but not why his son had to die.

The father said he expects to return to Katmandu with his wife. He will let his daughter and eldest son--who arrived Thursday for the funeral--stay if they want to.

But there is no reason for him to remain, Matshyendra said.

“As a man, I did this for my children. I didn’t come here for any other purpose.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.