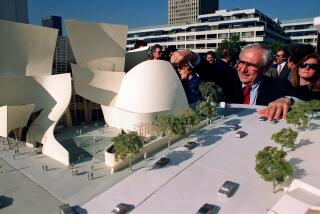

Conducting at a Prime Rate : Britain’s ex-leader Edward Heath shows his podium prowess

- Share via

NEW YORK — Edward Heath may no longer be Britain’s Prime Minister, yet he remains a singularly busy man. Not only is he the Member of Parliament for Old Bexley and Sidcup, he is active in charity work for the disabled, is heavily involved in fundraising for repairs to Salisbury Cathedral (Heath owns a home just inside the cathedral close), and is a champion deep-water sailor. He is also an inveterate world traveler, author, a founder of the European Community Youth Orchestra, and an internationally active conductor.

Yes, conductor. In fact, though he was on these shores recently for a 36-hour fund-raising trip on behalf of Salisbury Cathedral’s aging spire, this interview was in conjunction with the MCA Classics release of his new recording. Made with the Zingara Trio and the English Chamber Orchestra, the recording is of Beethoven’s Triple Concerto and Boccherini’s Cello Concerto in G.

He has long loved the Triple and believes it is underrated because of unbalanced performances. Most conductors, he explains, “look for three of the great and good, and bring them together, and say ‘now play the Beethoven Triple.’ You can’t get, in my view, a properly balanced, or perfect performance, by doing it that way. Karajan did it with Oistrakh, and Richter and Rostropovich, the great and the good, but they all do the phrasing in their own way. I sent Karajan (the late conductor was a close friend) a copy of mine, and got back a very complimentary letter saying this really does seem to have got Beethoven properly together.”

Though he had been conducting from the age of 15, and as an organ scholar at Balliol College, Oxford, was responsible for all the on-campus music--church and concert--Heath’s podium prowess did not become a matter of international public awareness until 1971, when he led the London Symphony Orchestra in a performance of Elgar’s “Cockaigne” Overture (later issued by British EMI) as part of a gala concert.

“If you’ve been used to speaking to thousands of people in political meetings, what an orchestra can do is really small in comparison, from the point of view of causing troubles. . . . If you know what you want, and how to get there, then they’ll respect you. It’s the people who don’t really know what they want who the orchestra can’t play with.”

Prime minister from 1970-1974, Heath was in charge of negotiations at the time Britain first applied to join the European Economic Community. During Heath’s tenure as prime minster, the United Kingdom became a member of the organization.

“Cockaigne” was part of another historic event in his musical career--the first gala benefit concert to be held in the Peoples Republic of China, in 1987, which raised $1.25 million for the disabled. For the program, played in the Great Hall of the People (another first, arranged by Deng Xiaoping) and telecast twice to a total viewership of about 400 million, he told them: “We’ll do ‘Cockaigne’ because I want something English; we’ll then do the Tchaikovsky ‘Rococo Variations’ because Tchaikovsky was one of the better Russians, and that brings in Europe. And then we’ll do Dvorak’s ‘New World’ because we were the new world, now we’re the old world, you’re the new world, and you’d better make a better job of it than we did!”

Later, Heath said two Chinese journalists asked him: “You have spent your life as a politician, but also as a musician. Now politics is reality and music is fantasy. Can you tell us how you’ve combined these two things throughout your life?” “I said: ‘Well, it’s a very interesting philosophical question. But you must get one thing right from the beginning. It’s music which is the reality and politics which is the fantasy, and never get mixed up about that.”

And yet, the tragic events of this past summer were all too terribly real to the man who had restored diplomatic realtions between his country and China in 1972. “Horrifying, really. We must try and get them back on the right lines again. I think at the beginning (Deng) didn’t really know what was going on with the students.”

Was all the media exposure an unfortunate application of salt on wounds? “I think that after all the events, it was. But if one is saying this was a repressive regime, then why on earth did they keep all the telephone lines open? And all the world’s television teams filming what was going on the whole time. . . . Well, why did they allow all that to happen? It points to the fact that really at the top they just didn’t know and reach any decision about it. And they were embarrassed by Gorbachev seeing all this going on.”

Returning to the West and to music, the matter of music education in the schools arose. Unlike the U.S., the British have kept classical music a high priority in the schools. “I think here we have been in the forefront in educational music. In our schools, basically everybody has classical music. In my political area, I’ve got 50,000 voters; there we’ve got three school symphony orchestras, full strength.”

Heath deplores the current government’s supermarket supply-and-demand philosophy that says the arts must pay for themselves. “The arts have always depended on support, sponsorship of some kind, and there is a limit to which business will engage in sponsorship. And (when) firms find their profits falling then this is one of the first things they’ll cut.”

Heath is also troubled by what he perceives to be the narrowness of the programming in the concert halls, which in his opinion focuses too much on the contemporary at the expense of the broad spectrum. The man who used to cycle 72 miles to London for a week of Promenade Concerts reminisces wistfully that “when I used to go to the Proms as a kid, we had Monday night which was Wagner night. Beecham called it “Bleeding Chunks of Wagner,” but at least one had the opportunity of hearing all the great episodes. Wednesday night was Haydn/Mozart, Tuesday night was modern, Friday night was always Beethoven, and Thursday was very largely British. Well, if you have six weeks on that basis, there’s very little in fact which you haven’t heard.

“Now, the great fashion is, you must mix everything up. . . . What happens in that process is that the present younger generation miss out on the basics of life, which is Bach, Beethoven, Handel, Haydn and the rest of them, which I think is a pity. . . . We’re given a diet of Mahler, spicings of Bruckner, Stravinsky, Shostakovich and so on. This I think is regrettable. But it’s also true that it’s much easier to conduct Mahler and get away with it--I’m not referring to any specific person --than to (conduct) a first-rate performance of Haydn.”

The concert halls are not his only worry:: “A mania seems to have seized the world of opera that you must be different. . . . It’s even happening at Glyndebourne, I’m afraid. I sometimes say to them--when they are polite enough to ask--’You know this is really ghastly.’

“This year they did ‘Figaro’ with ancient instruments. They said: ‘Isn’t this wonderful that we’re now doing this?’ I said: ‘I think it’s absolute nonsense. . . .’ A lot of people were excited to begin with and then shocked at the result. And they said: ‘Well of course it’s because they’re in an orchestra pit, and when these instruments were originally used they were on the floor on a level with the audience.’ So they then raised the pit a bit. And of course for the other performances, the orchestra complained that they were raised, and the audience complained that the noise was too great from the orchestra. So they got caught both ways.”

Clearly, Heath is no fan of the ancient instruments stars. “Music is a universal and ageless language.” To him, the ancient instruments movement puts music into a museum. “It’s interesting to go and look at pieces in museums, because they represent an earlier age with which one’s not acquainted. But one doesn’t say: “I’m going to take this out of the museum and use it in my ordinary life.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.