Tarkovsky’s ‘Solaris’ at Nuart: Philosophical Space Adventure

- Share via

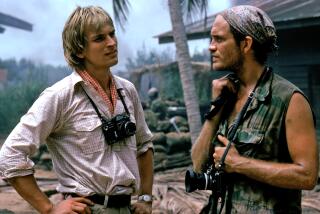

In August, 1976, the Nuart hosted two sold-out screenings of “Solaris,” the late Andrei Tarkovsky’s dazzling 1972 science-fiction film that, like Stanley Kubrick’s “2001,” served as an outer-space adventure and a meditation on the meaning of life. If you were among those turned away at the box office, you’re getting another chance: “Solaris” returns to the Nuart Wednesday to begin a full week’s run.

The film is the odyssey of a Soviet psychologist (Donatas Banionis) who travels to a space station hovering over a remote planet named Solaris. It seems that the Soviet government would actually like to abandon the station, regarding reports of some of its findings as too incredible to believe. What ensues allows Tarkovsky to contemplate basic philosophical issues through the interplay of science, philosophy and emotion in a quest to determine the relative importance of each.

“Solaris” is also an unabashedly romantic work in which the primacy of love is asserted--but as one of the film’s characters observes, “To preserve the truths we need mysteries.” (Note: On Friday there will be only one showing, at 7 p.m., of “Solaris.”)

Screening Tuesday at separate theaters are two outstanding documentaries on two very different artists. Robert L. Burrill’s “Illuminations: Ruth Bernhard, Photographer” will be at the Nuart along with Meg Partridge’s delightful “Portrait of Imogen,” a study of Bernhard’s late friend and colleague, Imogen Cunningham. Meanwhile, Ken Burns’ “Thomas Hart Benton” will be presented at 8 p.m. at UCLA’s Melnitz Theater as part of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ “Contemporary Documentary” series.

In temperament and personality, Bernhard and Benton couldn’t be more different, but both have been tenacious, dedicated and single-minded in the pursuit of their art. Benton died in 1975 while the San Francisco-based Bernhard continues to work into her 80s.

While acquainting us with the charming and vital Bernhard, Burrill surveys her six-decade career, beginning with her striking Art Deco abstractions to her later landscapes and sculptural nudes. Bernhard is a woman who in her own words has become one with nature, a woman who would rather be remembered for her love of life than for the work she did.

Burns’ documentary shows Benton conforming to the popular notion of what an artist and his life is like: He was a crusty, lusty man, a handsome, taciturn rebel who, as his sister remarks, “wanted people who read the funny papers to like his paintings.”

UCLA Film Archive’s wonderful “Dawn of Sound: A Tribute to Vitagraph” continues Saturday in Melnitz Theater at 7:30 p.m. with Alan Crosland’s “The Jazz Singer” (1927) and Brian Foy’s “Lights of New York.” Contrary to popular myth, “The Jazz Singer” was not Hollywood’s first talking picture; it was a silent film with a Vitagraph score and sound effects, plus Al Jolson’s famous ad-lib, “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet.”

“Lights of New York” was the first “100% All-Talking Picture.” “Lights” was a typical gangster melodrama in which two small-town innocents--lovely Helene Costello and her sappy beau (Cullen Landis)--become ensnared in Manhattan’s underworld. The immobility of the the early microphones takes its toll, but the seamy side of the Roaring ‘20s strikes an authentic note. Sunday’s 7:30 p.m. Vitagraph offering, Garbo’s “Divine Lady” (1929), lives up to its title, but the John Barrymore “Tempest” (1928) is another matter. For complete schedule: (213) 206-FILM, 206-8013.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.