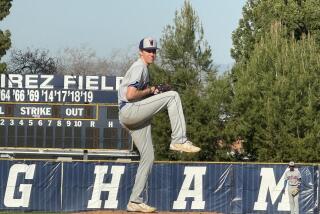

Feats OF Clayton : Northridge Standout Drives Opposition Batty With Ability to Hit and Pitch

- Share via

There have been three-hit games, memorable home runs and, as a pitcher, a couple of complete-game victories.

So why does a certain 0-for-a-USC game so quickly come to mind when Craig Clayton, pitching ace/outfielder/infielder reminisces about his 1 1/2 seasons as Cal State Northridge’s leading hitter?

“It was a feeling,” he said. Actually, two of them.

First came the sensation of butterflies--the rather large Monarch species--going full flutter in his stomach. What previously had been a mild case of the freshman jitters quickly became severe when CSUN visited USC’s Dedeaux Field in midseason last year.

“Before the game, I was real nervous,” Clayton recalled. “We got there and I saw the pictures of guys like Freddie Lynn and Mark McGwire on the wall and I was intimidated. I thought, ‘This is Division I. These are the guys you hear about all the time.’ ”

But nine innings, three fruitless at-bats and a couple of hours later, Clayton departed with a new outlook.

“After the game (a 4-2 CSUN win), I thought, ‘Those guys weren’t any different than me,’ ” Clayton said. “Even though I didn’t get a hit or do anything special, I knew then that I had the capability of playing at their level.

“After that game, my attitude changed a lot. I felt like I belonged.”

Indeed, Clayton has proven his mettle as a major-college performer during his short stint as a Matador.

As a freshman, Clayton led Northridge with 70 hits, 38 runs scored and a .314 batting average. This season he has defied the sophomore jinx and become a dominant force at both ends of the 60-feet 6-inch spectrum.

Clayton’s team-leading .403 batting average is third among California Collegiate Athletic Assn. hitters. He also leads CSUN with 56 hits, a .465 on-base percentage and seven pitching victories.

Oh, he belongs all right. But perhaps more so at the Division I level than Division II. Which is just what CSUN Coach Bill Kernen was hoping when he plucked the 6-foot, 170-pound right-hander from Cypress College’s clutches.

Clayton, an All-Orange County performer at Anaheim’s Loara High in 1988, was hours from attending his first class at Cypress when Kernen, the midnight caller, swooped in with a scholarship offer and stole him away.

“He came up here the next day instead of going to class,” Kernen said with more than a trace of relief. “We probably made that one by about an hour or so.”

Had Clayton attended a class at Cypress, he would have been unable to accept Northridge’s offer. Instead, he signed with the Matadors that afternoon.

But why a player of his caliber was bound for a junior college in the first place remains a mystery.

Clayton was one of Orange County’s top high school hitters with a .485 average, three home runs and 22 runs batted in. He also carried a 3.67 grade-point average, which was considerably higher than his earned-run average of 3.00, so the academic side was not a problem.

Kernen was not hired as CSUN’s coach until the summer of ‘88, so he had an excuse for recruiting tardiness. But he can only guess why other coaches skirted Clayton on their annual pilgrimage through one of the nation’s brick-dust hotbeds.

Clayton played mostly third base when he wasn’t pitching for Loara, leaving Kernen to surmise that no team needed a third baseman.

“People knew he was a good player,” Kernen said. “He was on all the all-star teams. I really couldn’t say why nobody picked him up. I’m just glad they didn’t.”

Before he landed the Northridge job, Kernen had seen Clayton play for Loara. But when it came time to recruit a third baseman, Kernen chose to sign Denny Vigo out of El Camino Real High.

Then, during the summer, Kernen saw Clayton play for various all-star and youth-league teams--only his position wasn’t always third base. He roamed the outfield, pitched and played shortstop too.

And, as always, Clayton hit.

“When I saw that he could play a lot of positions, I knew we could use him somewhere,” Kernen said.

Somewhere turned out to be just about everywhere.

As a freshman, Clayton played outfield, shortstop and second base in addition to pitching 6 2/3 innings. This season, Clayton is a regular in the outfield when he isn’t pitching.

Kernen would rather not use his starting pitchers as position players, but Clayton has forced him to make an exception. And it’s a good thing, because Clayton says that having to stop doing one or the other “would be like having to quit half of baseball.”

He pays a price for such versatility. After pitching into the ninth inning and earning a victory over Grand Canyon (Ariz.) last week, Clayton had ice applied to most of his upper torso.

As he chatted with reporters, a trainer wrapped ice bags around Clayton’s right elbow and both shoulders. The left shoulder was treated because a line drive had squarely struck him there.

But he was back in the lineup playing left field the next day.

More difficult than the physical soreness that follows each pitching start, Clayton said, is the mental fatigue.

“It’s a drain,” he said. “In high school, you basically throw and get people out. Here you have to hit your spots, stay down and battle more. It takes a lot of concentration.”

So too does the transformation from pitcher to hitter and back again during a game. Unlike his National League equivalents who bat ninth and are largely content to move baserunners along with a bunt or fly ball, Clayton generally hits from the No. 3 position and has the responsibility of extending an inning with a hit or walk.

This role is especially important for Northridge, which has Scott Sharts, the CCAA leader in home runs, batting cleanup.

“We he gets up there and we need a hit to keep an inning going, it’s gotten to where I just know he’s going to get it,” Sharts said. “It’s automatic. Seems like every time.”

Clayton’s success on the mound has not come with quite the same regularity, although his 7-3 record and 58 strikeouts in 67 innings are best among CCAA pitchers.

A curve, changeup and running fastball form Clayton’s pitching repertoire, but it is competitiveness, the same trait that most benefits him as a hitter, that is his best attribute, said Dave Weatherman, CSUN’s pitching coach.

“When a team strings a couple of hits together and gets something going, that’s when you have to bow your neck and reach in for that little extra you need to stop a long rally,” Weatherman said. “That’s what Clay has done real well the last couple (of) times out.”

Strangely, Clayton is more dangerous offensively--20 hits in 40 at-bats--during games in which he pitches. When he loses, Clayton is an even tougher out; he has nine hits in 13 at-bats. All of which could give a person the wrong impression.

Clayton, although his pride might be battered by each opponent’s hit, does not enter the batter’s box with anything but a poker face. No scowl. No bulging neck veins. No imprints left on the bat’s rubber grip.

“You can’t tell whether he’s pitching bad or good. He’s the same person every time up,” said Mike Sims, CSUN’s freshman catcher. “When he comes to the field, (whether it’s) in practice, in a game, (or) when he’s pitching, he’s always all business.”

How long baseball will remain Clayton’s business is questionable. With a fastball that is timed at only 80 m.p.h., the odds of him pitching professionally would seem long. Clayton’s speed afoot also is limited, hampering his prospects as a professional outfielder.

However, should he continue to hit . . . Well, there’s always room in the majors for a hitter somewhere.

Even if it’s everywhere.