Secretary-of-State-ism : The Past Four Have Been Exceptional--Especially Bush’s Baker

- Share via

A secretary of state can be the President’s Machiavelli, his Richelieu, or his foreign-policy alter ego--but he cannot be President. It is the power of the presidency that enfranchises him; major foreign-policy decisions are by definition presidential calls. All appreciations of America’s foreign ministers must be seen in this perspective.

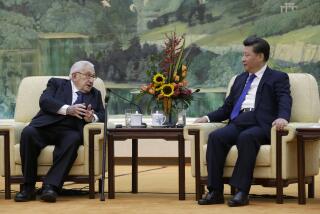

Nonetheless, recent U.S. secretaries of state have been exceptional. While not everyone admired his Realpolitik views and supernova-size ego, Henry A. Kissinger, the Harvard professor, was highly respected in international diplomatic circles and no doubt served both Gerald Ford and Richard Nixon well. The likable Cyrus Vance, the New York lawyer, was also respected, despite serving under a weak President, and was a particularly skilled negotiator. And fusty George Shultz, though no personality king, was solid and thoughtful and brought to the top table of U.S. diplomacy a useful knowledge of international economics that far exceeded that of any of his predecessors--and that of many foreign counterparts.

And it now looks as if President George Bush has a good one, too. Just in recent weeks, Secretary of State James A. Baker III has worked to turn U.S. policy toward Cambodia on its heels, cooperated skillfully with his Soviet counterpart Eduard Shevardnadze on the delicate question of Germany and the thorny problem of Afghanistan.

He has done all this while keeping U.S. diplomacy in balance as Eastern Europe divorced communism and Lithuania filed for separation from Moscow and China returned to the Dark Ages.

Secretary Baker’s nuanced stance toward the Boris Yeltsin phenomenon in Russia is typical of his unyielding pragmatism. Even while wishing Mikhail S. Gorbachev well as he labors to maneuver his country toward a new economic and political order, the United States has signaled that it is ready to open official contacts with the Soviet president’s major non-Communist opponents. Such a move would be welcome; staying in touch with a regime’s political opposition is always prudent and, usually, mutually helpful. But even here, Baker moves with typical caution. He says that, before acting, Washington wants to see if a true multi-party non-Communist opposition emerges out of the country’s current political turmoil. That’s wise: The United States would be hurting itself--along with the prospects of Soviet pluralism--if it seemed to be trying to anoint an opposition leadership.

Of course, there is an obvious flaw in the Bush Administration’s cheery but cautious pragmatism. It is less a foreign policy than a modality of diplomacy. There is no overarching strategic plan--everything is tactics, posture, thrust and counter-thrust. A famous British phrase is useful here: “muddling through.” The Bush-Baker approach is not intellectually or emotionally satisfying. There is a sense that the United States may only be one jump ahead of the next foreign-policy crisis.

But better to be one jump ahead than one jump--or more--behind. In this fast-moving world, there’s a virtue to pragmatism that is often unappreciated. For grand strategic plans can have their down sides.

Consider postwar Soviet foreign policy: Unswerving, ideological, fixed on certain goals. But now, as Moscow applauds a united Germany, accepts this new Germany in NATO and has to grudgingly swallow almost all that is going on in Eastern Europe, the Soviet grand plan has been thoroughly repudiated--consigned to the dustbin of history.

So if the pragmatism of James Baker will never seem Churchillian, it will never seem rigidly John Foster Dulles-like, either. In a very rapidly changing world, the advantage of conducting a foreign policy that is not set in cement but that reacts quickly and intelligently to new stimuli and unexpected developments is not to be underestimated.

Pragmatism in pursuit of a peaceful foreign policy is no vice.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.