Concert Etiquette Essay Elicits a Chorus of Responses

- Share via

I am pleased to have received so much response to my essay on etiquette at concerts--whether one may applaud between movements or only at the end of a composition.

I concluded that I was not against spontaneous applause at the wrong time because it encourages the musicians, gives people a chance to cough and gives everyone a moment of relaxation.

Rodney Oakes of San Pedro disagrees: “Multimovement works, such as a symphony or a concerto, are entities in their own right. The pause between movements simply allows for the establishment of a new tempo, tonal center, and a contrasting mood. The break does not indicate that the piece is completed, and applause at these spots destroys the aesthetic continuity of the piece, interrupts the performers’ concentration, and generally weakens the overall focus of the work. . . .”

OK. I’ll never do that again.

Barry T. Jensen has a suggestion that might help those who want to do the right thing. He says conductors and musicians ought to give consistent signals. “I suggest that conductors face their orchestras, arms outstretched, after each movement, and turn to the audience only and immediately at the end of the number. Soloists ought to lower their instruments (unless they are pianists) and smile or nod. . . .”

Karl Oldberg of Santa Monica says the rules of applause should not be changed, for reasons similar to those advanced by Oakes, but also condemns the local tendency to give standing ovations.

“I attended concerts for some 40 years in Chicago, where there was never , with one exception, a standing ovation, and that was not for the performance but because everyone in the hall knew that they had just heard, for the very last time, a performance by Rachmaninoff.

“On another occasion the audience remained seated while the orchestra gave Bruno Walter a ‘tusch.’ This is where the players toot their instruments, saw on the strings, beat the drums and make a great show of both acknowledgment of greatness and of affection for a great musician.

“By the way,” he adds, evidently referring to my presumption in writing about the subject, “sciolists should write only about what is a part of their expertise.”

(But a sciolist, which I certainly am, is one who pretends to more knowledge than he has; thus, he may write about any subject that he pretends to understand.)

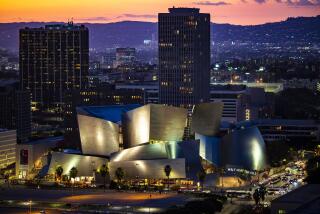

That the question of audience response is not simply academic is illustrated by an incident described by W. H. Henry of Downey. “My wife and I were seated in the balcony at Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. At the end of an aria most beautiful, a fellow two rows down emitted an ear-splitting, two-fingers-in-the-mouth whistle, waking up most of the balcony.

“A very large lady rose slowly from her seat, turned majestically toward the culprit and informed him, ‘One does not whistle at the opera!’ He unpleasantly replied, ‘I whistle when and where I damn please!’ The argument escalated until an usher separated the two by moving the man to an orchestra seat.”

“I am an opera lover,” writes Marjorie L. Schwartz, “and no one seems to find any objection to applauding after every aria in an opera. Why the big deal about applause after movements in a symphony?”

Nevertheless, after a concert in which the conductor showed his displeasure with inter-movement applause, she wrote this verse:

An American custom

in need of improvement

is allowing the audience

to applaud each movement

On the subject of shouting bravo to show one’s appreciation, I have some support for my argument that bravo is enough, and that one need not shout brava or bravi to suit gender and number.

“The dictionaries agree with you,” writes Irving R. Tannenbaum of West Los Angeles College. “Bravo need not be declined to become brava or bravi. Only Webster’s Third alludes to this by saying ‘sometimes restricted in use to a man.’ The OED does not even list brava or bravi. I agree with you that this is the kind of pedantry up with which we should not put.” (I must note that Webster’s also lists brava separately: “used interjectionally in applauding a woman.”)

A case in point: “At one of the recent Bolshoi ballet performances at the Shrine,” writes Harald Johnson, “I noticed a front-row aficionado (or was it an aficionada?) near me pointedly shouting bravo toward the male dancers, brava to the females, and bravi to the rest.

“I couldn’t help chuckling at the thought of an Angeleno hurling Italian phrases at Soviet ballet dancers.”

By the way, both D. Wayne Doolen and Ivan Kelley complain that my phrase “a large number of those in the crowd applauded between every movement” combined a grammatical monstrosity with a physical impossibility.

Doolen recalls reading of the death of a minor Hollywood celebrity who died “between visits to his physician,” observing that “the statement may have been grammatically correct, but the sequence would have been physically impossible.”

Kelley and Doolen are quite right. Bravi, gentlemen!

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.