Wrong Direction on Civil Rights : It doesn’t force quotas--Bush shouldn’t veto it

- Share via

If President George Bush makes good on his threat to veto the Civil Rights Act of 1990, it will not only be an act of unfeeling misgovernment, but also another sign of his party’s failure to resolve the contradiction between what it says it intends toward minority Americans and what it actually does for them.

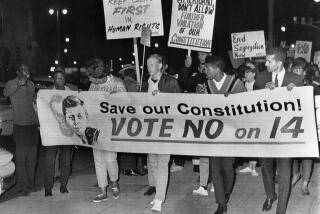

When former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke ran for the U.S. Senate as a Republican, Bush and other GOP leaders were sincerely horrified and rushed to repudiate him. They have been less quick to forswear their party’s historic antipathy toward civil rights legislation--an antipathy that made it easier for Duke to call himself a Republican, however uneasy it made GOP regulars feel to hear him say so.

President Bush and the other Republican leaders of his generation are the architects of a strategy designed to wean Southern white and Northern ethnic voters away from their traditional Democratic loyalties. The key element in that approach is the anxiety both groups share about the legal and economic gains women, African-Americans and other minorities have made as the result of the civil rights movement. The GOP’s strategy has been an electoral success, but it all too frequently has turned the the party of Lincoln and Emancipation into the party of white male privilege through obfuscation.

It is, of course, the habit of American political discourse to excuse inequality through euphemism: states’ rights, separate but equal, reverse discrimination. The circumlocution Bush employs to justify his hostility to the Civil Rights Act of 1990 is “quotas.” The President insists the bill will force quotas despite the fact it explicitly says, “Nothing in the amendments made by this act shall be construed to require or encourage an employer to adopt hiring or promotional quotas on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin.” But Bush recently wrote: “I am convinced that it will have the effect of forcing businesses to adopt quotas. . . It will also foster divisiveness and litigation. . . and do more to promote legal fees than civil rights.”

These observations are hard to reconcile with the bill’s explicit disclaimer and its actual provisions. The Civil Rights Act of 1990 aims to reverse six recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions that have weakened existing federal laws against employment discrimination. Among other things, it requires that employers once again bear the burden of legally justifying practices or policies whose objective effect is to create discriminatory patterns in hiring or promotion. It also allows victims of sexual, religious or ethnic discrimination to seek the same compensatory and punitive damages already available to those who have suffered racial discrimination. Fair-minded people will search such proposals in vain for the dire consequences over which Bush frets.

The President already has said he will allow a bill restricting advertising on children’s television to become law without his signature, even though he personally feels it abridges some First Amendment freedoms. Americans are entitled to wonder why he cannot do the same for the Civil Rights Act of 1990.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.