Mexico Archeological Dig Yields 1st-Ever Carving of Decorations on Child’s Teeth

- Share via

CIUDAD VICTORIA, Mexico — Archeologists say the tombs of a mysterious city have yielded the first example of the use on children of an ancient art: carving or engraving teeth as a sign of beauty.

Evidence of the engraving was discovered on the teeth of a boy’s skeleton found in the ruins of Montezuma’s Balcony, where civilization was far more advanced than any previously thought to exist in the region.

Montezuma’s Balcony is 310 miles north of Mexico City outside Ciudad Victoria, capital of northeastern Tamaulipas state. Its name is derived from that of Moctezuma, the Aztec king.

Tamaulipas, which spent more than $53,000 on the project, plans to open the site to the public this year.

Two canyons and a mountain surround the remote, 12-acre city. It is reached by a steep, rocky road that veers two miles off the main highway to 86 huge slabs of stone named the “grand stairway.”

Only from the top of the stairway can the remains of more than 100 circular structures be seen, each up to 50 feet in diameter, built from stacked and fitted rocks.

More than 100 skeletons were found in basements, along with ceramic fragments, food-grinding utensils, pipes, necklaces, arrowheads, knives and small figurines.

The remains of the boy, no older than 5, showed evidence of the carving, called dental mutilation, in his two upper incisors and one lower incisor.

“This is a very rare find,” said Jesus Narez, director of the Montezuma’s Balcony restoration project. “Until now, we have never detected dental mutilations in a person this young.”

In primitive cultures, dental mutilation was believed to be practiced only on adults. It still is done in some Brazilian, Indonesian and African communities.

“We think it hurts a lot, but . . . peyote, which was commonly used in those times, was probably used to put the child to sleep or dull the pain,” Narez said.

Several other things make Montezuma’s Balcony unique, said Narez, curator-investigator of the architectural and cultural collections of northern Mexico at the National Museum of Anthropology and History in Mexico City.

He said two groups of people lived there: the Grassiles, thin and fine featured, and the Robustus, big-boned and heavy. Archeologists chose the names.

“At least for now, we think they lived there together, but radiocarbon testing is being done to determine if they were there at the same time or if one group followed the other,” Narez said.

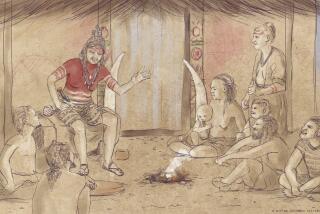

According to Narez, the city’s 3,000 people probably lived between the years 600 and 1400. The elite occupied the structures and were buried in their basements, and the others lived in wooden huts, he said.

References to Montezuma’s Balcony appeared in a researcher’s report in the mid-1800s, and there was another report in the 1940s. Work on the site began in 1988 and was completed in August.

Although their culture achieved more than others in the area, the Montezuma’s Balcony residents were not as advanced as the Teotihuacans, Zapotecs or Mayas of southern Mexico, who built pyramids and cities in the same period.

Northern tribes such as the Huastecas and the warrior-like Chichimecas led more primitive, simpler lives than the people of Montezuma’s Balcony, Narez said.

“We never thought we’d find these types of buildings so far north,” he said, adding that huge pieces of rock used to build the structures were moved with the aid of planks and rope.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.