Hammer Had Vision Others Lacked

- Share via

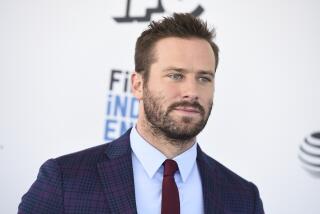

Armand Hammer, who died Monday night at age 92, was an entrepreneur on a grand scale, one of a rare breed who make a difference in worldwide business, in good ways and bad.

Hammer was admired for his unceasing energy and for his efforts on behalf of better relations between the Soviet Union and the United States. He also made enemies--among people in the oil industry who blamed him for making a separate deal with Libya in 1970 and opening the gate to higher energy prices, and others who criticized him for running Occidental Petroleum as a personal fiefdom.

The truth is that entrepreneurs such as Hammer are not necessarily model citizens. But through their quick wits and daring they often contribute to change in the world and set an example of how much business can really accomplish.

Hammer was part of a rare breed. Others like him in business today include Ted Turner, Rupert Murdoch and Akio Morita--prickly personalities but with a lot more dash and daring than typical corporate managers.

Business to Hammer was more than the pursuit of money. Hammer died rich, to be sure--his stock holdings in Occidental Petroleum are worth more than $30 million.

But after a business career spanning seven decades, Hammer was not rich enough to qualify for Forbes magazine’s list of the 400 richest Americans--partly because his personal wealth had been reduced by millions given in philanthropy.

Hammer, like all entrepreneurs, had an instinct for making a dollar. He made $1 million even before he graduated from medical school by buying and selling supplies of ginger--a key ingredient for a popular semi-alcoholic drink in Prohibition New York. He also sold real whiskey, which he later said he had purchased before the Prohibition law took effect.

It was in the Soviet Union, where Hammer went in 1921 with medicines from his family’s pharmacy in the Bronx, that he achieved his greatest success. He had an entree to the market because his family had emigrated from Odessa, and his father was a prominent Socialist who knew Lenin.

But Hammer didn’t simply sell medicines and come home. He saw that the country was starving, so he set up a deal to bring in U.S. grain in exchange for Russian furs.

He didn’t stop there. Seeing needs to fill in the Soviet Union, Hammer became an importing agent for Ford Motor, U.S. Rubber, Underwood typewriters, Parker Pen and dozens of other firms.

In order to get the right to import, he set up a network of fur-trapping stations in Siberia so that he could expand fur exports.

Today, U.S. business people have difficulty figuring out how to get paid in the Soviet Union. But entrepreneurs are seldom stalled by such difficulties. In Hammer’s case, the Soviet government, which was a partner in his trading company, could pay him only in unconvertible rubles. But Hammer saw art treasures in the Czar’s Hermitage Palace in Leningrad and asked for some of them in exchange for his work. He later sold the Russian art works in American department stores and through his own art gallery in New York.

In 1925, the Soviet government took Hammer’s trading company into state control. So he started a pencil factory--which was not an easy thing to do. The technology of pencils, according to a 1980 article in Forbes, was controlled at that time by A. W. Faber Co. of Nuremberg, Germany.

Hammer went to Nuremberg and paid higher wages to lure away Faber’s workers and their know-how. Within six months, Hammer had a new factory set up on the outskirts of Moscow, turning out $2.5 million in pencils per year.

Three decades later, Hammer was to use the same tactic to hire away exploration talent from major oil companies for Occidental Petroleum. And the tactic worked again. In Libya in the 1960s and in Colombia in the 1980s, Occidental teams discovered big oil fields on prospects that had been picked over and discarded by the giants Mobil and Exxon.

But other oil companies blamed him for giving the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries the upper hand in 1970 when Occidental buckled to the demands of Libyan ruler Muammar Kadafi, who wanted more money for Libya’s oil.

As a small company, Occidental was vulnerable, of course, but also entrepreneurs often see a little into the future. A year after Libya, the shah of Iran--with the tacit backing of the U.S. government--routed the oil companies and took control of the oil price for OPEC.

Hammer went on to build a good-sized company, with $20 billion in revenue last year--a long way from the couple of wells in which he had invested $50,000 in 1956. He built the company by wit and promotion, often using his art collection as a calling card with communities and countries in which he sought oil concessions. He promised the art collection to the Los Angeles County Museum, but later reneged and housed it in a monument to his own name.

He also hung on long past normal retirement and indulged in numerous projects that others saw as ego trips.

But one person’s ego trip is another’s grand gesture. After the nuclear power plant accident at Chernobyl in 1986, Hammer underwrote the mission of U.S. bone marrow specialists to treat the radiation victims. Hammer’s critics said he was bucking for the Nobel Peace Prize, but so what? The important thing is that the specialists got to the radiation victims.

What do we get from entrepreneurs such as Hammer? We get new ideas, said economist Joseph Schumpeter. Hammer’s new idea was to see beyond ideology to what business could accomplish--an idea embraced today in the Soviet Union. Take him, warts and all: Hammer made a difference.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.