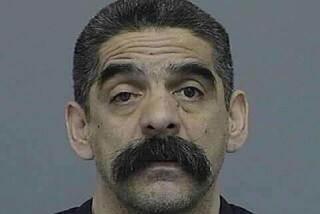

Contra Figure’s Slaying Was Seemingly Foretold : Nicaragua: Enrique Bermudez was the enemy both to the Sandinistas and rebel leaders. His political activity served to reopen war wounds.

- Share via

MANAGUA, Nicaragua — Death summoned Enrique Bermudez by telephone.

The call for the former top Contra commander came last Saturday to his sister’s house, his landing pad in the postwar Nicaragua he had known as a civilian for just four months.

He was going to stay home that evening, but the call changed his plans. As he left, Bermudez told the maid “a friend” had phoned to say that U.S. Ambassador Harry Shlaudemann wanted to meet him at the Intercontinental Hotel.

At 9:45 that night, Bermudez was found dead in the hotel parking lot. He had waited two hours in the bar--for an appointment the ambassador later claimed to know nothing about--and gone back, apparently alone, to his Cherokee Jeep. The killer had stalked him and put a bullet behind his left ear.

The phone call had set in motion what government investigators call a meticulous plot against one of the U.S.-backed Contra’s most notorious figures. A week later, the identities of the caller and the killer remain unknown.

That mystery is high political drama for President Violeta Barrios de Chamorro. The assassination has shaken Nicaragua like no other event since she ended the Sandinista revolution with an electoral upset a year ago this Monday and disarmed 18,000 anti-Sandinista rebels last June. Failure to solve it, her aides admit, could invite revenge killings and undermine Chamorro’s efforts to heal this bitterly divided country.

To many who knew Bermudez, the deeper mystery is why the wily, 58-year-old career soldier let his guard down. Why, they ask, did a man with so many enemies on both sides of an eight-year conflict that claimed 30,000 lives trust that voice on the phone? Wasn’t he suspicious of being summoned to a hotel where, he should know, the American ambassador doesn’t hold meetings? And why did he go alone, unprotected in the night?

The tragic homecoming of Enrique Bermudez, told by friends and family, is the story of a soldier who wanted to leave combat behind but plunged headlong into political activity that reopened war wounds. It is also the chronicle of a man too fatalistic, too proud or even too naive to protect himself against a death that, in retrospect, seemed foretold.

A postwar amnesty did little to erase Bermudez’ special status among Sandinistas as the devil personified--an image owing to his direct sponsorship by the war’s CIA planners, his access to then-President Ronald Reagan and his rank as colonel in the widely despised National Guard of pre-revolutionary dictator Anastasio Somoza.

“If 45 years later the German people haven’t pardoned their war criminals, why should Nicaraguans, after six months, pardon ours?” asked the Sandinista newspaper editorial that greeted Bermudez’ return to Nicaragua last Oct. 18. An angry war widow was more direct. “There may be peace and reconciliation and kisses from Dona Violeta,” she warned him over a radio call-in show, “but if I see you on the street I’ll kill you.”

Bermudez’ gruff, authoritarian manner, his alleged padding of CIA expense accounts and his comfortable life in Miami had also earned him enemies among young rebel field commanders who actually fought the war. “He’s a dictator, just like Noriega or Castro,” said former Contra operations chief Walter Calderon after one of several revolts against him.

Finally, last February, he was ousted as chief commander by Israel Galeano and Oscar Sovalbarro, men half his age and more eager for an armistice. Unemployed in Miami, he watched restlessly as the new government dangled $30 million in U.S. resettlement aid to disarm his fighters, as the promise of farms for all Contra veterans fell short and as Galeano and Sovalbarro feuded for control of the veterans’ fractious political movement.

Friends in Washington, Bermudez claimed, had once promised him $100 million for resettlement. If he returned to Nicaragua and regained control of the movement, he told a fellow Contra figure, he would lobby for that aid.

His wife and mother feared for his safety. Stay in Miami, they pleaded.

“I have a saint behind me who always protects me,” he assured them.

In Managua, he tried to interest a friend in starting a security agency to protect foreign embassies, but he didn’t move to protect himself. He shed his government car and driver after a month, borrowed the Cherokee from a friend and drove it himself, often unaccompanied, on missions chronicled by the Sandinista press as scandalous--to petition for the return of four personal properties seized during the 10-year revolution, to gain support from Contra veterans, to revive Somoza’s old Liberal party.

“He was trying to regroup 18,000 ex-combatants and their families, with financial backing from the Liberals,” said Roberto Ferrey, a former member of the Contras’ civilian directorate. “That was a political threat to the Sandinistas.”

Last November, Sandinista officers still controlling the police arrested former rebel leader Aristides Sanchez. They accused him and Bermudez, who was not detained, of plotting with disgruntled ex-Contras to topple the government. “Bermudez runs the risk of losing his life,” a police official warned Sanchez before he was expelled from Nicaragua.

Hearing this, Bermudez penned a letter to Cardinal Miguel Obando y Bravo, the Roman Catholic leader. “If something happens to me,” he wrote on Nov. 21, “I hold responsible all those who conspire with the Sandinistas.”

But he stayed in Nicaragua another month, returned on Feb. 1 and rarely mentioned the threat among friends.

“We would run into each other in the street, each of us alone and unarmed,” said Adolfo Calero, an old rival in the rebel movement who returned last May. “Enrique waited longer to come home, but once he did he became overconfident. He thought he had earned the right to live in peace and enjoy his country. He believed too much in the spirit of reconciliation.”

Searching for his fatal flaw, other Contras recalled how Bermudez billed the CIA for dozens of bodyguards at the base camp in Honduras but kept only a handful on the payroll. “I was scared to be around him then, he was so unprotected,” a former employee said.

“As a military man, don’t you carry a pistol?” Obando recalled asking Bermudez last year.

“No,” the cardinal quoted his reply. “Whoever wants to kill me will find the right moment, and a pistol won’t help me when I’m fixed in his sight.”

The week before he died, Bermudez spoke at two meetings of Contra veterans. Petitions circulated with hundreds of signatures asking him to press demands for land, housing and financial aid on the government. Some veterans said that Sovalbarro, the movement’s president, felt challenged and heatedly urged Bermudez to leave Nicaragua. Sandinista commentators took that story as possible evidence of intrigue within the rebel ranks.

“The suspects are many, because many were his enemies,” said El Nuevo Diario, a Sandinista newspaper. “He moved in a secret world of conspiracy and power rivalries among allies and antagonists alike.”

Rebel officials and foreign diplomats doubt the theory that his killer came from the ranks of his allies. Despite wartime CIA manuals counseling assassination, they argue, the rebels never formed urban hit squads. That was more the Sandinistas’ style.

In any case, investigators say, the murder was apparently carried out by a well-organized ring.

Moments before the victim walked out of the hotel, both remaining taxi drivers left the parking lot with clients. A van crashed into the rear of a waiting car there, distracting the chauffeur’s attention. By the time the van sped away, Bermudez lay in a pool of blood beside his Jeep. A 9-millimeter Walther PPK pistol, which may or may not have been his, lay on the front seat with his glasses and keys.

Despite the elaborate precautions, investigators said four witnesses gave a description of the killer: a dark, heavyset man, apparently a Nicaraguan in his mid-30s, who fired a silencer-equipped pistol from six to seven feet behind the victim.

“If the Sandinistas did this, it was a side of them Bermudez underestimated,” said Luis Mora, a former rebel collaborator. “He knew the Sandinistas on the field of battle, but he thought the war was over. He didn’t know them so well in the field of treachery.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.