COLUMN ONE : General Has Heart of a Romantic : Schwarzkopf, the soldiers’ champion, is gruff, engaging and often quick-tempered. His men follow him with a loyalty that borders on idolatry.

- Share via

RIYADH, Saudi Arabia — Eighteen months ago, before a dinner honoring him in Kuwait, the general’s hosts had suggested that appropriate dress would be the traditional dishdasha robe and he had thought to himself, “Holy smokes, Schwarzkopf is going to dress up like the Kuwaitis and all the Arabs are going to say, ‘Who the hell does this guy think he is?’ ”

The general, though, was easily persuaded, and before dinner he took possession of a splendid embroidered dishdasha delivered to his hotel room. He slipped it over his bear-like frame and studied his image in the mirror, first from one perspective, then the other.

“It’s wonderful,” he said. And suddenly Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf was waltzing with his reflection, doing the same little three-step that T. E. Lawrence, widely known as Lawrence of Arabia, had done in the desert when he shed his British uniform for Arab robes and went on to form an alliance of Arabian tribes.

If Schwarzkopf is not Norman of Arabia, he is at least a soldier with the heart of a romantic, a man intrigued by Arab history and culture and a man who has followed his famous father’s footsteps through the sands of the Middle East to lead a war that may shape the world into the 21st Century.

“The stakes,” he says, “are higher than any conflict since World War II.”

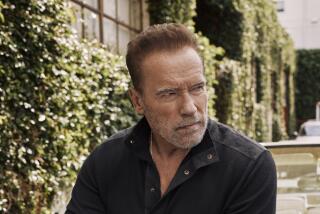

Gruff, engaging, sometimes hot-tempered, Schwarzkopf has a hearty laugh that can be heard down the corridor and a presence that fills the room. He is 6-foot-4, 240 pounds, with linebacker shoulders, upper arms as big as tree trunks--and a row of four stars on his collar. Sometimes he refers to himself in the third person. He seems to like privates as much as colonels and colonels more than politicians, and he makes his points with a furrowed brow and eyes that hold steady like a laser-guided bomb. No one ever left a meeting with him wondering who was in charge.

“What would I change about myself?” he asks. “I would probably”--he reaches for the words carefully--”want . . . a little more . . . patience. I wish I wasn’t so quick to anger. Any time I anger, I feel terrible about it afterwards, and if I ever think I have devastated a human being because of my temper, I always make it a point to go back to them and apologize.

“An awful lot has been written about my temper. But I would defy anyone to go back over the years and tell me anyone whose career I’ve ruined, anyone whom I’ve driven out of the service, anyone I’ve fired from a job. I don’t do that. I get angry at a principle, not a person. For instance, we keep having accidents here that kill people. Accidents that are caused by gross negligence. Why . . . should . . . one single life . . . be wasted?” His voice starts to rise.

Though his staff is sometimes intimidated, Schwarzkopf’s men follow him with a loyalty that borders on idolatry.

“You scared?” he asks, and the downcast soldier sitting on a duffel bag, headed for the front, turns around, startled to see whose hand is on his shoulder. Schwarzkopf hunkers to talk, elicits a smile and exchanges salutes.

“We’ll get you home as soon as we can, I promise you that,” says the general, who believes that there is no higher calling in life than that answered by the ground-pounding, muddied, dog-faced, rifle-bearing foot soldier.

Schwarzkopf felt that way, too, during the Vietnam War--his two Purple Hearts awarded there, he says, are tribute to the poor marksmanship of his enemy--but he came home from that war embittered.

Now, 20 years later and 3,000 miles away, he has shaped his leadership of Operation Desert Storm from the lessons of Vietnam: no body counts; no gradual build-ups; no border sanctuaries for enemy troops, and no unescorted journalists running helter-skelter around the battlefield.

In rallying a flag-waving American public to the support of half a million U.S. troops here, he has orchestrated the final reconciliation between the American people and the military.

“I guaran-damn-tee you,” he said before launching the first attacks Jan. 17 against the world’s fourth largest army, “that if we fight, we will win.”

H. Norman Schwarzkopf Jr.--the H. stands for nothing and he doesn’t use the junior--was born in Trenton, N.J., 56 years ago, the son of German immigrants. His mother, Ruth, was a nurse, his father, Norman Sr., a West Point graduate, Class of 1917. Young Schwarzkopf was raised color-blind and respectful of individual dignity.

Once, when he was 9 or 10 years old, he rose by instinct to give his seat to an elderly black woman on a public bus from Lawrenceville, N.J., to Princeton. The white people around him chuckled and kidded him. Schwarzkopf went home to his mother, confused and wondering if he was inherently privileged, if being white meant that you did not respond to those of another color.

“Remember this,” his mother replied. “You were born white. You were born Protestant. You were born an American. Therefore, you’re going to be spared prejudices other people will not be spared. But you should never forget one thing. You had absolutely nothing to do with the fact you were born that way. It was an accident of birth that spared you this prejudice.”

He recites his mother’s words today as if they had been spoken yesterday.

“I just grew up liking people,” he says. “I tend to judge people on what kind of human beings they are, and I like to be judged the same way. I like people to look at the net worth of Norman Schwarzkopf, and I hope they judge me on what kind of heart I have in me.”

Some of that heart, Schwarzkopf hopes, comes from his father, a man the son remembers as “a compassionate guy, a very tough commander loved by his troops.”

Norman Sr., the first superintendent of the New Jersey State Police, headed the investigation of the Lindbergh kidnaping in 1932 and hosted and narrated the popular shoot-’em-up radio show, “Gang Busters.”

Gen. George C. Marshall sent him to Iran in 1942 to organize Iran’s national police and train it to protect the supply route to the Soviet Union. Eleven years later, he played a pivotal role in a CIA operation that overthrew Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh and installed Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi of Iran. Western oil interests in Iran would remain in friendly hands for 25 years, until the cataclysmic arrival of the ayatollahs.

The senior Schwarzkopf, a major general at the time, wrote such voluminous letters about the people and culture of Iran to his family in New Jersey that one of his daughters, Sally, used to groan when they arrived, saying that reading them was like doing homework. But his son absorbed every detail, fascinated by the mysteries of a distant, exotic land, and when Schwarzkopf sent for Ruth and the three children to join him in Tehran in 1946, it was the most glorious adventure of 12-year-old Norman Jr.’s life. His fascination with the Middle East would never fade.

Young Schwarzkopf entered West Point in 1952, fulfilling an ambition he had held as a child. He had to endure an unusual amount of hazing as a plebe because of his famous father--upper classmen used to make him mimic the sounds of speeding cars and machine guns heard on “Gang Busters”--but he excelled, taking part in football, tennis and wrestling. He liked ballet but not baseball and heard the call of battle in Tchaikovsky’s “1812 Overture.” He sang tenor and led the cadet choir, and, with an IQ of 170, easily finished in the top 10% of his graduating class.

“I was immediately struck by his leadership ability and quick, alert mind,” recalls one of his teachers, Lt. Gen. Harold Moore, “and there aren’t too many I remember from the hundreds I taught there.”

In Schwarzkopf’s senior year, he led an underground rebellion against the artillery that traditionally attracted the academy’s top students, recruiting his best and brightest classmates for the Army’s least glamorous but most romantic branch, the infantry. The artillery that year was forced to include among its selections the Class Goat, the student ranked last academically among 485 senior cadets.

“Norm aimed for the top and expected to reach it,” says his West Point roommate, Gen. Leroy Suddath. “When he got his first star, he was already looking forward to his next promotion. He’s always looking for positions of greater responsibility.”

Schwarzkopf first went to Vietnam in 1965, believing deeply in the cause, and returned for a second tour in 1969. He performed bravely, once tiptoeing through a minefield to rescue a wounded comrade, and he was miserable when he was assigned as a staff officer to U.S. headquarters in the rear, where many officers seemed more interested in promoting their careers than winning the war.

“It was a cesspool,” he says.

After about six months, however, he was named commander of an infantry battalion in the 23rd (Americal) Infantry Division.

On one occasion, he refused to take his Vietnamese unit into battle because commanders had forgotten to order adequate air and artillery support. On another, his profanity could have melted the radio when he had helicopters overhead carrying VIPs but couldn’t get any of them to pick up a badly wounded soldier.

In 1970, the parents of a GI named Michael Mullen blamed Lt. Col. Schwarzkopf, the battalion commander, for their son’s death by U.S. artillery fire. The incident became the subject of C. D. B. Bryan’s book, “Friendly Fire,” which, in the end, exonerated Schwarzkopf and portrayed him as a courageous and honorable officer. But Schwarzkopf’s anger and frustration grew--with bungling politicians, with foggy military goals, with the lack of public support at home.

“My brother as a young man was carefree and witty and charming,” says his sister, Sally. “He went over to Vietnam as a heroic captain and came home very serious. He lost his youth in Vietnam.”

And now, a generation later, he’s in another war, so different in design and execution. Schwarzkopf, who commanded ground troops in the problem-plagued invasion of Grenada in 1983, runs America’s high-tech war from an underground basement in the Saudi Defense Ministry and lives in what looks like a pensioner’s boarding-house room.

There is a double-barreled shotgun in the corner. The Bible and an edition of World War II German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s “Infantry Attack” rest on a bedside table. Nearby is a photographic collage of his family--wife Brenda, a former TWA flight attendant he met 21 years ago at a West Point football game; children Cindy, 20, Christian, 13, and Jessica, 18, whom he had been scheduled to drive to her first semester of college the day he left for the Middle East; and a black Labrador named Bear.

“I don’t see the famous temper at all,” his wife says. “He must leave it at work. He loves relaxing at home and being with the children--tennis, hunting, fishing, just being together.”

Schwarzkopf also enjoys watching “Cheers,” “Jeopardy” and Charles Bronson movies, although his family admits that he is so competitive hardly anyone will play Trivial Pursuit with him any more.

His knowledge of the Middle East--and his belief that Americans need to dismiss stereotypes and learn something about the culture and history of the Arab people--has served him well. In November, 1988, he took over U.S. Central Command, a paper command with a staff of 700 based at MacDill Air Force Base near Tampa, Fla., and began discarding antiquated scenarios that dealt with the Soviet threat to the region.

“This stuff is bull----,” he said. The threat to U.S. interests and Gulf stability, he reasoned, was far more likely to come from Iraq, which, with the end of the eight-year-long Iran-Iraq War, could now resume its quest for power and influence in the Gulf.

Five days before Iraq invaded Kuwait last Aug. 2, Schwarzkopf called 350 members of his staff together at MacDill for a paper exercise. He told them to draft plans to protect the Gulf’s oil fields from Iraq and added, “Oh, by the way, as far as strategy is concerned, you have to be prepared to protect U.S. regional interests, too.”

“Internal Look ‘90,” as the exercise was called, was polished up and became the model for Operation Desert Storm.

The operation, said Defense Secretary Dick Cheney, “is basically Norm’s plan. It’s fundamentally Norm’s to execute.”

Schwarzkopf has spent hours reading about the military men he most admires: Alexander the Great, who conquered the known world by the age of 30, Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce Indians, Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, Gen. Creighton Abrams. He studied the battle of Cannae where, in 216 BC, the Carthaginians under Hannibal crushed the forces of Rome in the first real war of annihilation. And he examined the Iran-Iraq War in finest detail.

But the man he has had the most difficulty fathoming is Saddam Hussein, whom he dismisses with the ultimate insult one field commander can bestow on another: “He is a terrorist, not a military man.”

“I guess,” Schwarzkopf said in December before the war, “the $64,000 question right now is: Is this a case where he would sacrifice his nation rather than be perceived in the eyes of the world and the Arabs as having backed down? I think it’s a flip of the coin.”

The coin came up tails. On Jan. 16, having received a top-secret message from the Pentagon, Schwarzkopf wrote a message to his troops: “. . . I have seen in your eyes a fire of determination to get this job done quickly so that we all may return to the shores of our great nation. My confidence in you is total. Our cause is just! Now you must be the thunder and lightning of Desert Storm. May God be with you, your loved ones at home and our country.”

Close to midnight, as the first U.S. bombers were about to take off for Baghdad, Schwarzkopf met with his staff in the underground war room on Prince Abdulaziz Street and asked the chaplain, Col. David Peterson, to say a prayer.

“This is it,” the general said when Peterson had finished. “Remember, everything you do is going to affect the lives of our troops.”

Schwarzkopf knows full well that the American people expect him to win the war and win it decisively. He knows as well that he could be the first American general since World War II to lead the country to victory and emerge from the smoke of conflict as a military hero. And that, he says, is getting things all backward.

“You don’t have to be a hero to order people to go into battle and risk their lives,” he says. “But you have to be a hero to go into the battle. The generals aren’t the heroes. The troops are.”

Researcher Helaine Olen contributed to this article.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.