He Always Had the Right Chemistry : Caltech to honor living legend Thursday: Linus Pauling, twice a Nobel winner

- Share via

A working celebration at the California Institute of Technology this week suggests a need for a third theory of relativity.

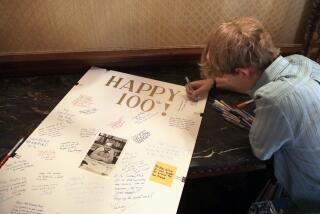

The event is the first of eight symposiums that Caltech has planned to mark its centennial year. But the Thursday event will be a double celebration, a daylong tribute to Linus Pauling on his birthday.

What suggests a need for a third theory is that Caltech is 100 and Pauling will only be 90 that day, but he somehow seems to be gaining on the school where he studied, taught and did breathtaking research for some 40 years.

His field is chemistry, but his scientific curiosity seems unbounded, sometimes even undisciplined. For example, he narrowly dodged real trouble with Washington after the first nuclear bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 by explaining publicly how the atomic bombs were made, a highly classified secret that he puzzled out by himself.

He is a Nobel laureate twice over. His award in chemistry came in 1954 for seminal work in “chemical bonding.” It seems so simple now, but until Pauling figured it out, science could not say exactly what makes O2 stick to C to produce carbon dioxide or H2 stick to O to create water.

In the 1940s, Pauling identified the alpha helix as the basic structure in protein. J.D. Watson and F.H.C. Crick took it further in 1953 to postulate the double helix as the building block of genes and chromosomes.

Pauling’s second Nobel Prize came in 1962 for his courageous campaigning against war and particularly against nuclear weapons testing.

At 90, he is still doing original investigations in his laboratory and publishing findings, work he manages to fit in among speeches, scientific meetings and dinners in his honor.

This is the same Linus Pauling who probably is better known among Americans for his advocacy of Vitamin C than for his other work that may well make him the most important chemist of this century.

He didn’t discover the vitamin, but he made it a household name--and staple--two decades ago when he said people should take a couple of grams a day (he takes 18) because it was good for them. Since then, he has decided that the vitamin might even reduce the risk of cancer.

The jury is still out on Vitamin C, but not on Pauling’s other contributions. Five other Nobel laureates will join the symposium in his honor at Caltech, where the emphasis will be on chemical bonding, not vitamins, and the verdict will be extraordinary words about an extraordinary man.