REVERSAL OF FORTUNE : Corey Pavin Ended a 2-Year Winless Streak on the PGA Tour After He Returned to His Longtime Camarillo Golf Guru

- Share via

The funny thing about golfers--well, one of the funny things about golfers--is their constant, unwavering belief that they are just a slightly bent elbow or minor repositioning of their feet away from the alligator pond.

Among the weekend types, the philosophy runs along the general line of, “OK, so I shot an 81 today. But tomorrow I’ll be lucky to break 100.”

And among the professionals, the finest golfers in the world, there is the conviction that a job selling purple golf slacks to old men in a pro shop is imminent, even during their great successes.

Meet Corey Pavin.

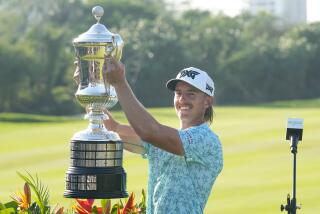

He currently is in the midst of shredding the PGA Tour, playing some of the finest golf of his life and standing second on the 1991 money earnings list on the tour after a brilliant victory in the Bob Hope Classic in February, a win that came just a week after he finished second in the Pebble Beach National Pro-Am.

Yet the former Oxnard High and UCLA standout is a nervous wreck.

You would think he was unable to hit anything off the tee except those screaming-weegie smother hooks, the ones that actually make a high-pitched whistling sound as they head for the condominiums. But his driving accuracy has never been better.

He would make you believe that from anywhere in the fairway, his chances of actually hitting the green with his shot were roughly the same as the PGA Rules Committee approving the use of bullhorns and the playing of tubas by the tournament galleries.

He won the Bob Hope by chipping in from 35 feet on the first playoff hole. But in his own mind, he is just thankful that the ball didn’t pop straight up out of the tall grass and hit him sharply in the eye.

And putting? Well, he figures a gopher could waddle onto the green and whack the ball with its tail and the ball would have as much chance of going into the hole as it does when he strikes it with his putter. Forget that he has made more tough putts already this year than the average golfer makes in a decade.

The reason for the pessimism, beyond the fact that he is a golfer and therefore instinctively fears the worst, is that Pavin went two years without winning a tournament. He had won seven tournaments in his first five years on the tour, and when the 24-month drought set in, Pavin came more than a little unglued.

“He was confused about himself and his golf swing,” said Bruce Hamilton, Pavin’s longtime teacher and confidante who is the pro at Las Posas Country Club in Camarillo. “He wasn’t happy at all with his performance on the tour. He had become very inconsistent, and his big thing was always the consistency. But he’d have a good round and then a bad round and play himself right out of every tournament.”

In 1989, Pavin’s best finish was a tie for 10th place in the Canadian Open. He played in 28 tournaments and not only failed to crack the top 10 but in five tournaments was asked to go home, given the PGA equivalent of a pink slip. He missed the 36-hole cut. And he tumbled to 82nd on the earnings list.

All of which was new ground for Pavin, who had enjoyed great success at the game since age 17, when he won the Junior World Championship in San Diego and later in 1977 the Los Angeles City Men’s Championship, the youngest player ever to win that title. At UCLA, he won 11 tournaments, including the 1982 Pacific 10 Conference championship. A year before that, Pavin’s brilliant play had earned him a berth on the U. S. Walker Cup team.

As a pro, he excelled again. As a rookie in 1984, he won the Houston Open and finished 18th on the money list. The next year he won the Colonial National and jumped to sixth on the money list. He won the Hawaiian Open in 1986 and the Hawaiian Open and Bob Hope Classic in 1987. He won again in 1988, at the Texas Open late in the year, but it was the only bright spot in a dreary year in which he tumbled on the money list from 15th the year before to 50th.

It was the beginning of Pavin’s long slide.

“The two years were horrible,” Pavin said. “At the low point, I’d go into tournaments feeling I had no chance to win. And for me, that was unbelievable. My whole career, if I couldn’t win it was never any fun for me. No fun at all. The competition is everything to me. And if I can’t compete, can’t be in the race to win every week, then there is no reason for me to be out here.

“I thought about quitting a few times and trying something else. But I honestly didn’t know what else I could do.”

What he did, finally, was call his friend Hamilton. And in one phone call, Pavin began to stem his slide toward PGA obscurity and perhaps even a slide into the world of purple pants and daily practice-range lessons for people who couldn’t break 85 on a miniature golf course.

Hamilton had worked with Pavin since the small 15-year-old kid sought him out in 1974. At the time, Pavin was a six-handicap golfer. Good, but in Southern California that put Pavin in a group of hundreds. But with the combination of Hamilton’s teaching skills and Pavin’s intense dedication to the game, the handicap began to fall. Within a year, Pavin was a scratch player, and colleges came calling.

While at UCLA, Pavin continued to work with Hamilton, and his game got even better. And when he qualified for the PGA Tour in 1983, the two stayed together, right through the tremendous rookie year and the seven tournament victories.

But then, toward the end of 1986, Pavin and his wife Shannon and son Ryan moved to Florida, 3,000 miles from the West Coast and, as it turned out, much too far from Hamilton.

“When he moved, we grew apart,” Hamilton said. “He found other teachers to work with him, but they didn’t think the same as I did and certainly didn’t know Corey like I do. He got confused. And then, about 15 months ago, he called. And now we’re back together. I don’t think it’s coincidence that his slump has ended. I’m not bragging about any of this, it’s just that I know Corey Pavin and his golf swing better than anyone else. Maybe even better than he does.”

Pavin, 32, still lives in Florida, but he and Hamilton have agreed to continue regular sessions. Pavin said he will return to the Camarillo area at least three times during the PGA season. And Hamilton will venture out onto the tour the same number of times to find his prized student.

“Corey got to the point where his confusion led to great doubts,” Hamilton said. “Golf is such a mental game, and when your confidence is gone, you are gone. He was asking himself, ‘Can I still compete? Can I ever win again?’ Everything played on his mind.

“We don’t want to have any more of those days.”

Toward that goal, Pavin has made more than just a slight commitment. A year ago, when it became painfully obvious that he needed Hamilton’s help on a regular basis to work out the tiny kinks that creep into every golfer’s swing, Pavin bought a large home just two blocks from Hamilton’s.

The real estate broker who sold him the house was Hamilton’s wife.

“I have to come here on a regular basis. I know that now,” Pavin said. “And when I do, I want my family to have a place to stay. I wanted to be near Bruce for the sake of convenience, and I still have my whole family living in the area, so we can turn the trips into nice visits.”

And if Hamilton’s help continues to breed the kind of success that 1991 has already brought, Pavin will be able to buy many more houses.

“Technically, it wasn’t any one thing that went wrong with my swing,” Pavin said. “It was a lot of little things, and they just snowballed. One thing leads to another and pretty soon you’re not hitting the ball well anymore and then you lose confidence and it gets ugly.

“When I was 15, all I could think about was the PGA Tour and how nice it would be, how simple it would be to play golf for a living. But as you get older, you start thinking more and it’s easier to get confused. Life becomes more complicated, the responsibilities you have increase so dramatically that you lose sight of the fact that golf is a game. I might never be able to make it just a game again, just a game the way it was when I was 15. But I’m going to try as hard as I can to get it back to that point.”

And, despite the stunning success of the first three months of 1991, the runner-up performance at Pebble Beach and the dramatic victory in the Bob Hope Classic and his 1991 earnings of $371,618, Pavin will not rest.

“People see what I’ve done this year and they figure I must be playing great,” Pavin said. “But that just is not true. There are lots of things I have to work on. I have lots of problems to work out on the course.

“I didn’t play all that well on the West Coast. Not at all. I played some bad rounds out here . . . some negative things happened.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.