BOOK MARK : Nixon Wasn’t Always a Cool Master of Foreign Affairs

- Share via

Even a partial list of developments during Richard M. Nixon’s presidency returns repeatedly to the “dark side” of the foreign policy over which he presided, and forces difficult questions about his supposedly effective conduct of the nation’s foreign relations.

He consistently supported, for example, the cruel colonels’ junta he found in power in Greece when he himself took office. He even managed, by conniving with the colonels to make their regime look better, to lift the arms embargo imposed on Greece by the Johnson Administration. Strong evidence suggests that Nixon was influenced more by Greek-American political contributions than by diplomatic or ideological concerns.

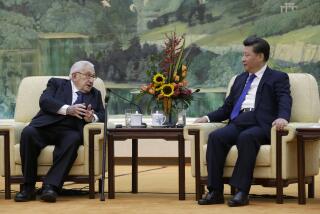

Nor was he always, in crises, the cool-headed analyst self-pictured in his books. In April, 1969, he wanted to bomb North Korea after one of its fighters inadvertently shot down a U.S. reconnaissance plane off the Korean coast. Henry A. Kissinger, then his national security adviser, egged him on, even talking of nuclear weapons--while simultaneously presenting himself to the press as a force for restraint. Cooler heads prevailed, as they might not have been able to do after Kissinger’s power escalated.

Similarly, in 1970, when Palestinian extremists hijacked several airliners and held more than 500 passengers as hostages, Nixon ordered a punitive air strike on guerrilla bases. It may be imagined what would have happened to the 500 hostages, many of them Americans, had not Defense Secretary Melvin R. Laird deflected the bombing order.

Nixon’s zealous pursuit of a flawed strategic arms limitation agreement ignored some important security considerations; and his overpraise of the result made future arms-control agreements less credible in Congress. His manipulation of intelligence estimates to serve his purposes undermined the Central Intelligence Agency and the role of reliable and measured intelligence. For only one example, he and Kissinger insisted that the Soviets were developing MIRVs faster than they actually were, to bolster their arguments for a ballistic missile defense.

Nixon’s lack of real interest allowed thousands of black Africans to starve in the cruel months just after the tragic Biafran war. His fetish for secrecy resulted in the damaging Nixon shokku --his shocker--to Japan caused by the opening to China, about which he had refused to consult the Tokyo authorities.

Nixon did not manage substantial improvement in prospects for an Arab-Israeli peace in the Middle East, although his and Kissinger’s diplomacy partially prepared the ground for the Camp David agreements reached between Israel and Egypt during the Carter Administration. The fall of Cambodia to the murderous Khmer Rouge was at least an indirect consequence of the illegal secret bombing and later invasion of that country.

Nixon’s high-handedness, sometimes exceeded by that of his national security adviser, led to unprecedented congressional restraints on presidential power. One example: the Case-Zablocki Act of 1972 providing for congressional review of executive agreements.

The War Powers Act of 1973, ostensibly preventing a President from waging undeclared war for more than 60 days, was another response to Nixon’s uses of power--particularly in Indochina. Brent Scowcroft, national security adviser to President Gerald R. Ford and later to President George Bush, called this legislation “almost certainly unconstitutional.” But he conceded it was an expression of frustration at presidents’ unwillingness to consult Congress on foreign affairs--an unwillingness exemplified by Nixon and Kissinger.

Congressional restraints and Nixon’s resignation--though his departure was specifically forced by domestic rather than foreign-policy acts--left the office of the presidency substantially weaker than Nixon found it. Inevitably, that meant that the chief executive’s ability to lead in foreign affairs was weakened, too.

Diminishing the office he inherits is the one sin against which every President swears eternal hostility. Even after losing his bid for the office in 1960, Nixon had too much respect for it to challenge the legitimacy of John F. Kennedy’s election. But when he finally attained the office himself, Nixon committed that cardinal sin--his actions weakened the presidency. And that fact alone deeply flaws the conventional belief that his was an unsurpassed mastery of foreign affairs.

1991 by Tom Wicker. Reprinted with permission of Random House.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.