Tiny Biotech Firms Need a Big Brother

- Share via

With the cost of bringing a new drug to market reaching stratospheric levels, small biotechnology companies are scrambling to form strategic partnerships with stronger, richer and bigger firms.

Genentech Inc., which flourished by licensing its own products to large pharmaceutical companies, is now on the other side of the equation, busy putting together research and development deals with small biotechnology firms.

“Biotechnology is probably the most difficult business to succeed in for a start-up company,” said Gary Lyons, vice president of business development for Genentech in South San Francisco. “The best relationship is where they have something we want and we have something they want.”

Establishing a working relationship with a larger, successful company in your field often means the difference between success and failure for a fledgling company. Cash is not the only benefit: The larger firm can provide you with expertise, access to customers and patented technologies.

These liaisons are especially critical for struggling biotechnology firms, which usually face an eight- to 10-year delay between discovery and distribution of a new drug.

“Now more than ever, small biotechnology companies need the market access of larger companies,” said Larraine Segil, founding partner of Lared Group in Century City. “Venture capitalists are not as free with their money as they were five to eight years ago, so for a company that requires four or five rounds of capital, it’s very difficult.”

Segil, whose firm has structured dozens of strategic alliances between big and small companies around the world, said a successful match has tremendous benefits for both partners.

“For a big company, the smaller entrepreneurial company is able to contribute its creativity and innovation,” she said. The smaller company benefits from an infusion of money and support that enables its research to continue.

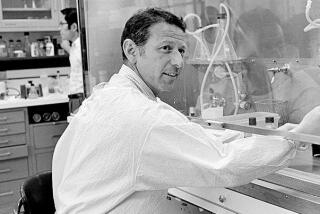

Stephen Sherwin, president and chief executive of Cell Genesys Inc., is well acquainted with the benefits of working with a big biotechnology company. Sherwin, former vice president of clinical research for Genentech, left to form his own company a few miles away.

“Our goal is to establish partnerships with larger biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies,” said Sherwin, whose Foster City, Calif., firm is pioneering ways to treat disease and genetic disorders.

Unlike many biotechnology start-ups, Cell Genesys has been lucky. So far, it has raised about $8.5 million from several venture capital funds and Stanford University.

Sherwin and his colleagues are exploring a new technique called homologous recombination. It enables scientists to replace, activate and deactivate selected genes within cells. The goal of homologous recombination is to permanently change cells, enabling them to serve as new ways to carry drugs or to combat disease themselves.

So far, one promising area for this technology is in the reversal or prevention of blindness associated with old age and certain diseases. Sherwin said his scientists are trying to engineer cells to replace deteriorated cells in the retina.

Although linking up with a big company may sound like the perfect solution to your money problems, there are dangers. Entrepreneurs who thrive on the excitement of running their own companies often chafe under the restrictions imposed by a strategic alliance.

Brian Atwood, vice president of operations at Glycomed Inc. in Alameda, has crafted three research and development deals with bigger firms, including a $15-million venture with Genentech. Together, Genentech and Glycomed hope to develop a line of anti-inflammatory drugs.

“The key to a successful relationship is to open up a broad front of communication,” Atwood said. “Each of us here talks to a different person in the organization we are working with.”

Segil agreed that communication is essential, especially since the initial excitement of a new working relationship often masks serious conflicts.

“A number of strategic partnerships we put together three or four years ago have experienced problems,” Segil said. “We find the commitment of energy and commitment to learn from each other changes with time.” The danger of a lopsided commitment, Segil said, is that “one side or the other feels taken advantage of.”

Often, the larger company’s policies and bureaucratic regulations begin to snuff out the creativity of the people at the smaller firm. Every management team also has its own view about taking risks, and sometimes this creates conflict.

“We tell clients it’s not a one-way street; there cannot be learning in one direction,” Segil said.