PERSPECTIVE ON THE BILL OF RIGHTS : Our Path Is Still Lit by Noble Ideas : In 1791, we amended our new Constitution to spell out the liberties claimed by independence; today, they are as vital as ever.

- Share via

Washington, D.C. , is a self-conscious city, laid out like a history lesson. Along the avenues of the Capitol Mall’s big cross are arrayed the gleaming temples of the Republic, the temples that celebrate the success of popular government and carry forward the work of that government in its third century. Thrust through the center of the cross is the austere height of the Washington Monument; to the north and south the cross is anchored by the White House and the Jefferson Monument, to the east and west by the Capitol and the Lincoln Memorial.

But if America has a true heart, it’s to be found a little distance from the mall and the monuments, in the rotunda of the National Archives on Pennsylvania Avenue. There--sealed in helium behind bulletproof glass, guarded day and night, shielded from light and fixed in a cage of steel and brass that rises on ponderous machinery from a basement vault--are the original copies of the three foundation documents of the United States: the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

It is fitting that words on parchment are our country’s crown jewels, for the impulse to get the fundamentals of government down in writing distinguished the political vision of the people living along the Atlantic Coast of North America long before they thought to call themselves Americans.

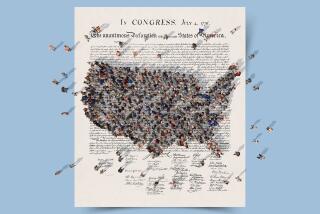

The United States of America was knowingly, deliberately created as a nation in a leap of faith unlike any other in history. What dwells at the core of American nationhood is not the memory of ancestral tribes or the names of dead kings and ancient battles, but certain noble words and a set of noble ideas about liberty and human nature that those words rest on.

From the outbreak of the long war against the British in 1775 to the beginnings of the first federal government in 1789, the American cause remained a revolution driven by words and ideals. Nowhere are the founders’ revolutionary, republican ideals so fully realized as in the words of the Bill of Rights, the first 10 amendments to the Constitution. Their adoption in 1791 was the consummation of a revolution that is still changing history.

The Declaration of Independence had proclaimed some of the “self-evident truths” that the Americans went on to win on the battlefields of the Revolution. Other “sacred rights” had been written into the Constitution itself. But the Bill of Rights remains the definitive catalogue of our individual liberties. The First Amendment alone guards the bedrock freedoms that citizens of many nations still do not possess: freedom of religion, with the complete separation of church and state; freedom of speech and of the press; freedom to assemble to protest or petition the government.

In the Second and Third amendments, the newly independent United States, wary of standing armies after the experience of British military occupation, sought protection in strengthening the state militias by confirming the people’s right to bear arms and by outlawing the quartering of troops in private homes.

The words of the Fourth Amendment, declaring “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures,” give each citizen a domain into which none of the instrumentalities of the state--not the police, nor the courts, nor any federal agency--may trespass without good and demonstrated cause.

Most of the rest of the Bill of Rights is devoted to safeguarding the rights of the accused in the criminal justice system, promising to all due process of the law, indictment by grand jury, a speedy and public jury trial in the locality of the offense, and counsel and witnesses for the defense. Explicitly denied to the courts are cruel and unusual punishments, excessive bail, self-incrimination by the accused and a second trial for the same offense. The framers wisely understood that we must jealously guard the rights of the accused, not to protect wrongdoers but to protect ourselves.

The last two amendments, Articles 9 and 10, quieted fears of a too-powerful federal government by claiming for the states or the people rights not specifically mentioned or granted by the Constitution to the national government.

Our Bill of Rights will always remain an unfinished document, just as the United States remains a changing and unfinished nation. Other amendments to the Constitution, like those that ended slavery and extended the vote to women, made overdue installments on that 200-year-old pledge, But the spare 450 words of the original 10 amendments endure, as noble and as powerful as any words ever written.

The United States has suffered its greatest agonies when it has failed to be lighted by the nobility of its founding words. But the act of creating America goes on, will go on as long as the people continue to hold up the immutable words of their charters to study them in the light of a new time, measuring the words’ promise against the actuality of the America they see around them. In the third century of our endeavor, the whole world is watching, too.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.