Man Behind ‘Big Bird’ Enjoys Anonymity

- Share via

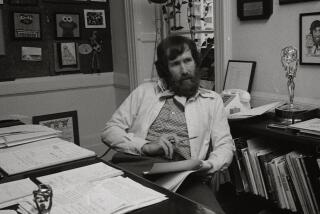

NEW YORK — Caroll Spinney for years has played one of television’s most popular characters, but most people have never seen or heard of him.

That doesn’t bother Spinney. “I love it,” he says convincingly.

Caroll who ? Try Big Bird, Spinney’s alter ego.

Spinney was handpicked by Jim Henson, the late creator of the Muppets, to portray “Sesame Street’s” lovable Big Bird and the irascible Oscar the Grouch. He decided early on that the bird, not the man, was going to be the star.

For years Spinney refused to be photographed at all. He still bans shots of him getting into or out of costume.

“It’s a delicate situation because the children think of him as a real bird,” he said. “That’s something we hadn’t planned on.”

Spinney, 57, early on turned down chances to do the talk show circuit with Oscar. Appearing as the puppeteer with the puppet would have brought him fame and padded his checkbook, “but I would have lost something too,” Spinney said.

Something such as the wonder in children’s faces when they look upon Bird, the love packed inside letters that come from around the world, the anonymity that allows him to pull off the occasional bodacious prank.

Once the unfeathered Spinney was in a department store and spotted a mother and daughter looking at talking Big Bird dolls. Overhearing the child’s name, Spinney crouched down and said, in Big Bird’s familiar falsetto:

“Hello, Elizabeth. Gee, that’s a pretty red dress! It’s snowing out, isn’t it?”

The mother was dumbfounded, wondering how the doll could know the name, the dress color and the weather, Spinney says. But the woman just took her daughter’s hand and they walked away.

“You mean, after all, that you’re not even going to buy the thing?” he called after her.

Spinney never did tell the woman who he was. And, looking at him, she never could have guessed.

Lean and wiry, with a thatch of white hair, cropped beard and trim mustache, Spinney, at 5 feet 10, is considerably shorter than Big Bird, who stands 8 feet 2. He bears a striking resemblance to Henson.

Spinney’s voice is pitched lower than Big Bird’s; his speech is infinitely more cultured than Oscar’s.

He and his wife, Debra, have a home on several wooded acres in northeast Connecticut. He would not say just where “only because I’ve actually had people drive into the yard, blow the horn and say: ‘Do the voice.’

“Yeah, get outta heeeeeere!” he says, slipping into Oscar the Grouch.

Spinney spends part of his free time making tapes for Big Bird toys and voice-overs for Bird’s appearances in Ice Capade-type road shows, which he refuses to attend. (“As a puppeteer, it goes against everything I do,” he explained. “The Big Bird in the show moves like Godzilla.”)

Not so with his own feathered garb, which is half costume and half puppet. Big Bird’s head--all 4 1/2 pounds of it--is controlled by Spinney’s right arm, held “as straight as possible” over his head. He monitors Bird’s movements on a 1 1/2-inch TV screen strapped to his chest.

Spinney was bitten by the puppeteering bug as a youngster. Along with his own mother he credits, of all people, F. Lee Bailey’s mom.

Bailey’s mother ran a day care school in their hometown of Acton, Mass. It was there that Spinney, a childhood playmate of the boy who became the noted trial lawyer, saw his first puppet show.

At age 8, Spinney made his debut in the family barn with a homemade monkey and snake, and earned the princely sum of 36 cents. He put himself through art school performing at birthday parties and lodge shows, all the while planning a career in drawing comic strips or illustrating books.

“I didn’t know that puppets would take over,” he said. In 1960, while still in school, he landed a job on the “Judy and Goggle” puppet show, a summer-replacement series at a local television station in Boston. His next stint was a 9-year run on the local “Bozo the Clown” show.

In 1969, Henson was scouting for someone to play Big Bird. He showed up at Spinney’s outdoor, animated light show, and a friendship was born.

Henson died just over a year ago, and “there’s a vacuum there that is just never going to be filled,” Spinney says.

Big Bird at first was “the village idiot on the show” because when Spinney asked Henson what kind of character he was, the Muppet maker described him as a Goofy-like sidekick.

Then one script gave him the real clue: Big Bird threw a tantrum because he wanted to go to day care with the rest of the kids. “From then on, I suggested we play him as a kid.”

As for the cantankerous Oscar, Spinney said, he was having trouble deciding what voice the trash-can troublemaker should have. Enter one cigar-chomping New York cabbie.

“I was going to meet Jim to do a run-through on Oscar for the first time. I was supposed to have a voice ready, and still couldn’t decide when I got into a cab and the driver said: ‘Where to, Mac?” It was the beginning of Oscar’s whiny, distinctly New Yawk speech.

“And (the driver) proceeded to talk about (former Mayor John) Lindsay, with a lot of f-words thrown in, and how he was ruining the city--and I just kept saying to myself, ‘Where to, Mac? Where to, Mac?,’ and I realized that sounded just right.”

Although Oscar is fun, Spinney confessed, “I like the Bird better.”

“I know and love the Bird. I like the little guy’s personality. I kind of think of him as, well, as a kid of mine.”

He said the realization came to him years ago, when the costume was vandalized during a campus performance.

“He was on a makeshift rack when I went to lunch, and all of a sudden I saw these ROTC boys and girls wearing their uniforms, and in their officer hats each of them had a yellow feather,” Spinney recalled.

He ran back to the dressing area and found Big Bird on the floor, an eyeball hanging limp and an 18-inch circle of feathers ripped away.

“I ran out of the building and, for about two minutes, fell on the grass in absolute hysteria. . . . It was like seeing your kid attacked. I never knew how I felt about him until I saw him lying there in the dirt. That really defined my feeling about him. He’s my kid.”

Even after two decades, Spinney said, he has no intention of moving on.

“I’ve been asked before are you tired of it? Do you want to go on and do other things? And I say, ‘Would you want to stop being Mickey Mouse?’ ”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.