Fast Math : Teachers Use Multiplication to Add Confidence

- Share via

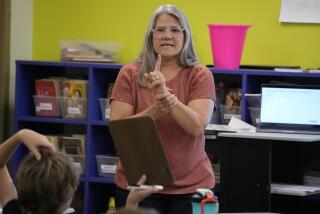

Diane Bonner’s students at Royal Oak School in Covina have become walking calculators by constant drilling in that bane of schoolchildren--the multiplication tables.

By early this month, students could shoot back answers to 9 times 7 and 12 times 11 faster than teachers could turn their flash cards. At a recent math tournament, the speediest student, 13-year-old Brian Cass, answered 64 questions correctly in 57 seconds.

That is especially surprising because Bonner teaches special education and all her students have behavioral or learning problems. But Bonner, who exudes an aura of firm but friendly authority, believes that any student can succeed if given the right motivation and respect.

“I was raised in Iowa with certain expectations and I sat in my class and thought, why should I expect any less of these kids?” said Bonner, 49. “Now, these kids have developed their skills to such acuity that long division and fractions are much easier for them.”

Math educators today generally place less emphasis on computational skills such as the times tables and more on critical thinking and problem-solving.

But some still embrace a back-to-basics approach and tout the multiplication tables for helping children develop speed and mental discipline that can be applied in higher math. The Kumon Educational Institute, for instance, has 380 learning centers in the United States that use a Japanese-inspired method of teaching math to increase speed and accuracy in calculation.

Bonner steers clear of the intellectual debate, saying that theories hatched in academic laboratories do not always pan out in a classroom filled with 30 noisy children.

Besides, Bonner says, she isn’t just teaching math skills. She is instilling self-confidence.

“When kids can blitz fractions because they can factor so fast in their heads, it turns them on and gives them good self-esteem,” Bonner says. “A lot of these kids are very aware that this class is different and the success they experience here makes them feel good about themselves.”

Consider 13-year-old Jeremy Smith. Last year, Bonner says Jeremy could not multiply with numbers higher than two. Today, he is comfortable with numbers and can multiply effortlessly into the table of 12.

“Other teachers tried for years to teach me math, but before Mrs. Bonner, I didn’t know anything,” says Jeremy, a tousled blond-haired boy with a wide smile.

“She has this really neat trick. You look at the numbers, you say them out loud three times, then you look away and say it three times, then you look back and repeat it.”

Ken Millett, director of the California Coalition of Mathematics, a nonprofit educational group that seeks to boost math aptitude, calls Bonner’s program an important first step.

“This is an opening for them to explore exciting things,” Millett says. “It’s really encouraging to see this enthusiasm and it demonstrates that the capacity for math achievement is greater than people believe.”

Allan Simmons, a special education administrator for the California Department of Education, says it is impossible to know how unusual Bonner’s program is.

“It sounds like she’s doing something exciting that we would encourage,” he said. “We’re always looking for new methods that work with kids.”

Bonner, who began teaching in 1974, honed her skills at Los Angeles County’s McLaren Hall School and at a county-run school for severely emotionally disturbed and abused children. She came to Royal Oak in the Charter Oak United School District three years ago.

“Before I ever discipline a child, I look at what’s motivating their bad behavior and what will motivate them to succeed,” Bonner says. “A lot of teachers put children down and don’t give them the full benefit of dignity and respect, but if you extend those courtesies to a child, they respond and try harder to please you.”

Bonner says the multiplication competition as a way to motivate students started out as a bet with teaching partner Scott Nagel. The teachers, both of whom work with special education students, pitted their classes against each other in rounds of competition.

Susan Rainey, superintendent of the Charter Oak District, was on hand to watch the sixth-, seventh- and eighth-graders whiz proudly through the math tournament.

Rainey calls Bonner “a great motivator.” Many of the students “have not thought of themselves as academically oriented, and now they are seeing themselves succeed, both among their own peer group and across campus,” Rainey says. Bonner somewhat sheepishly admits that her fastest students can beat her at the multiplication tables.

“I challenge any teacher anywhere to get their kids, get a clock and start cranking those cards. It isn’t as easy as it looks.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.