Former Soviet Nuclear Lab Seeks U.S. Aid

- Share via

CHELYABINSK, Russia — The chief scientist of the top-secret laboratory that once designed Soviet nuclear bombs appealed to Secretary of State James A. Baker III on Friday for money to keep his staff at home and at work on peaceful projects.

Yevgeny N. Avrorin said the scientists, some scraping for enough money to feed their families, did not want handouts or make-work jobs. But he predicted that all of them would stay in Russia if their lab remains open and finds the money to support challenging projects, such as using controlled explosions to produce industrial diamonds.

Baker said the United States and Germany are negotiating with the Russian government to create a scientific clearinghouse in Russia to sponsor peacetime projects. He said the idea is very close to the plan advocated by Avrorin and his colleagues.

Baker said Washington and Bonn want to provide work for former Soviet scientists so they would not sell their knowledge to Libya, Iran or other regimes seeking a back door to the nuclear club.

Earlier, some U.S. officials had considered employing some scientists in the United States or other Western countries. But Baker made no reference to that suggestion in his speech to about 100 of the former Soviet Union’s best scientists.

“We know that right now your options at home are limited and outlaw regimes and terrorists may try to exploit your situation and influence you to build new weapons of war,” Baker said. “It’s the highest priority of the United States and our allies . . . to help you overcome your hardships and avoid that terrible choice.”

But Vladislav L. Nikitin, the facility’s deputy director, said there has been no rush by the former Soviet scientists to sign up with the Libyans or any other radical regime. He said none have left the institute and, as far as he knows, none has received a job offer abroad. He suggested that Baker may only make the problem worse by talking about possible defections.

“The kind of people who are ready to leave the country--there are none here right now,” Nikitin said. “However, all the noise . . . about ‘brain drain’ that the secretary of state is talking about today, that is having an impact on our scientists and to a certain extent is initiating this.”

The institute, described as Moscow’s answer to the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, is set behind a triple barbed-wire fence in the midst of a birch forest on the Siberian side of the Ural Mountains. It is one of 10 secret military research-production facilities in the Chelyabinsk region, the heart of the Soviet military-industrial complex since World War II.

Although one of the other compounds in the area was visited by a U.S. Senate delegation late last year and by a few reporters since then, the lab that Baker toured on Friday had never before opened its doors to an American.

About 25 miles to the south of it is the site of a 1957 nuclear waste explosion that rivals the Chernobyl power plant disaster as the worst nuclear holocaust since the bombing of Nagasaki. Some of the surrounding area is still too radioactive to use for agriculture or most other purposes.

Nikitin, briefing reporters after the public opening of Baker’s meeting with the experts, said the average salary for scientists at the lab is 1,300 rubles a month, with the pay going up to a top of about 1,500 rubles monthly. At the current tourist exchange rate, the top pay is less than $15 monthly. Presumably, at that price, Washington and Bonn could afford to just pay the scientists’ salaries.

But Avrorin, the scientific director, rejected that idea. He said payments for doing nothing “are not acceptable. To a specialist, it is not only important to have money for living but also to have interesting and challenging work.”

The institute had no trouble projecting a certain threadbare quality. Baker addressed the scientists in a drab auditorium that looked more like an aging college classroom with a blackboard in front and blue-gray paint on the walls. Later, when Baker’s party toured the labs, they saw equipment that one official said appeared outdated.

There is an insular quality to the place, which may prove to be Washington’s best card in keeping the scientists from signing up with individuals such as Libya’s Moammar Kadafi. Families have worked here for generations; many people spend almost all of their lives in this remote site, a two-hour drive from the nearest metropolitan area, Ekaterinberg, the recently renamed Sverdlovsk.

Until 1987, lab employees were prohibited from traveling abroad. Avrorin said he now knows that such isolation is bad. He appealed for more contact with American mathematicians and scientists.

Avrorin and Viktor Mikhalov, deputy minister of atomic energy of the Russian Federation, said Baker plans to discuss details of his clearinghouse proposal with Russian President Boris N. Yeltsin in Moscow on Monday; for that reason, Baker did not provide details to the scientists.

Avrorin said that the production of tiny industrial diamonds by controlled non-nuclear explosions “can bring profits starting this year.” He said the lab could be making money on fiber optic communications in two years. He also suggested research on medical uses of radiation.

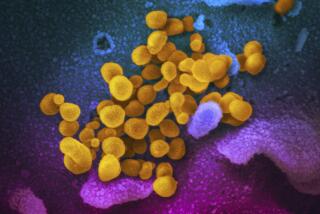

After the meeting, Baker donned a white smock, white hat, plastic shoe covers and radiation dosimeter for a tour of the facility. He peered at a tiny bit of plutonium through a microscope and looked at other equipment. No work was being done at the time.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.