MOVIE REVIEW : ‘Babe’ Gets to Base on Bunts

- Share via

George Herman (Babe) Ruth has always seemed too much of a subject for movies to handle: too big, bumptious and prodigiously skilled, too rude and gloriously unfettered. And “The Babe” (citywide) is only the latest in a line of failed attempts to tame or capture his spirit.

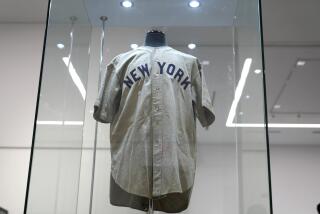

It’s a movie somewhat undone by its own hero worship. Intelligent, well-intentioned, highly professional in all areas, it still can’t capture its subject--the legendary New York Yankees home-run king--because it’s too bent on arguing his case. It tries to clean up the Sultan of Swat--not in the squeaky-clean, bowdlerized fashion of the pallid, pulpy 1948 “The Babe Ruth Story,” but in a more knowing, modern manner.

The film doesn’t shy away from the “dark” side of Ruth’s history: the Rabelaisian gastronomic and sexual orgies that accompanied his first blast of fame. But it sometimes seems to overapologize for those peccadilloes and squelch every belch. These filmmakers want us to “understand” the Babe. But how can you truly comprehend a force of nature? A staggeringly gifted athletic “natural”--probably the best pitcher in baseball before he turned hitter-outfielder and demolished the home-run records--Ruth doesn’t need alibis.

Watching “The Babe”--with its careful period decor, well-researched script, sumptuous Haskell Wexler lighting and sincere, well-crafted direction by Arthur Hiller--is like watching a highly professional but dull baseball game where the runners are being bunted from base to base. No one is going for the fences--though John Goodman, who’s playing Ruth, is more than capable of it.

In many ways, Goodman is perfect for this role. An athlete himself, he’s been made up to an uncanny likeness of Ruth; he’s worked hard at capturing the persona, the mannerisms, even the left-handed batting and pitching stances. Ruth was a natural clown, and so is Goodman: a graver, more cerebral clown, but someone who really understands the big man’s joys and demons, the massive roaring appetites driving him on.

Yet there’s a kicker. Goodman has a tendency to play against his size, rein himself in. His great movie performances to date have been in “Barton Fink” and “Raising Arizona,” where he’s kept volcanic passions mostly under control--and that reticence sometimes works against him here, because the movie itself is too controlled.

Beginning in the boys school, St. Mary’s, where Ruth’s Baltimore tavern-keeper dad incarcerated him, allegedly for truancy, “The Babe” tends to present his life as a pageant, a series of nostalgic tableaux. We see all the famous Ruth anecdotes--the “called shot” in the 1932 series, the “guaranteed” homer for bedridden Johnny Sylvester--and we meet colorful or famous figures, sometimes for only a second or two.

There’s teammate-cohort Jumpin’ Joe Dugan (Bruce Boxleitner), wives Helen (Trini Alvarado) and Claire (Kelly McGillis). Yet, for all the dramatic or emotional impact they make, they might as well be the famous gangsters, including Al Capone, who recite their names to Ruth in a speak-easy and then vanish. Ruth had trouble remembering names; he tended to call everyone “Keed,” “Kiddo,” “Sister” or “Mom”--and the movie is full of kiddos and sisters too. Producer-writer John Fusco has a tendency to write archetypal characters and scenes and that’s what most of “The Babe’s” supporting cast is: archetypal tough priests, shrimpy managers, stingy owners, gum-chewing newsboys or golden-hearted babes.

Fusco may be torn by conflicting impulses. He obviously wants to revive a spirit of heroism in American movies, here as well as in “Crossroads” or “Thunderheart.” But he’s also accommodating a post-feminist age that’s suspicious of heroes, especially super-masculine types like Ruth: probably the quintessential American unruly boy-male. And Hiller, a compassionate, sensitive director who’s usually at his best with brash or iconoclastic scriptwriters, like Paddy Chayefsky, may be too discreet here.

In general, films on American sports legends--even the supposedly classic ones, such as “Pride of the Yankees” (which co-starred Ruth, in a comic turn, as himself) or “Knute Rockne, All American”--suffer from a kind of waxy gentility, full of cleaned-up heroes and slick sentimentality. Sports movies are usually better, freer, when they don’t deal with heroes or champions, true or not; when, like “Bull Durham” or “White Men Can’t Jump,” they concentrate instead on the spontaneous joy and vernacular of athletics.

There is a dark or pathetic current to Ruth’s story: Money slipped through his generous fingers, the cash-hungry Yankee organization stiffed him. But the major thrust of his story lies in his character and his immense impact on his times, the way he came to symbolize the ‘20s. He was an outsize man in an outsize arena, an overgrown boy, or “babe,” with outsize appetites pulling him down. And, in this movie, everything instead seems smaller-scale, cuter, more manageable.

At the height of his fame, the real-life Ruth, the most remarkable sports figure in a time that worshiped sports heroes like no other, was so powerful and unabashed that he could face the President of the United States--corrupt, weak, mediocre Warren G. Harding--and ask, grinning: “Hot as hell, ain’t it, Prez?” That’s the core of Babe Ruth--an unbuttoned proletarian sports genius in a decade of unbuttoned plutocratic excess--and that’s what “The Babe” (rated PG) doesn’t seem comfortable with. It’s not a bad movie. But its sentiments are faster than its reflexes. By the time it tries to uncoil a home-run swing, the ball has already vanished.

‘The Babe’

John Goodman: Babe Ruth

Kelly McGillis: Claire Ruth

Trini Alvarado: Helen Ruth

Bruce Boxleitner: Jumpin’ Joe Dugan

A Universal Pictures presentation of a Waterhorse/Finnegan-Finchuk Production. Director Arthur Hiller. Producer/screenplay John Fusco. Executive producers Bill Finnegan, Walter Coblenz. Cinematographer Haskell Wexler. Editor Robert C. Jones. Costumes April Ferry. Music Elmer Bernstein. Production design James D. Vance. Art director Gary Baugh. Running time: 1 hour, 53 minutes.

MPAA-rated PG.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.