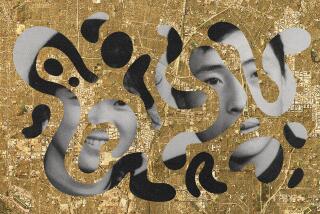

Reactions to the Riots

- Share via

The Los Angeles riots and their aftermath evoked strong emotions among Asian-Americans who spoke about their reactions to the upheaval and their relationships with other Asian-Americans. I’d be outraged (if my store was looted) but I don’t believe in using guns. By golly, I’d cuss the heck out of the looters. But I’d just forget about it. I don’t think Japanese believe in carrying a gun.

--Jimmy Jike, 81, Japanese-American, retired, reacting to Korean shopkeepers defending their property with guns during the riots.

Some folks thought, what will mainstream America think? But others were saying under their breath, “right on.” (The Koreans are) breaking the stereotype of passive Asians . . . (but) I think (Japanese-Americans) were concerned that a foreign government was in the U.S. asking for reparations for a community in the U.S. It could have made the Korean-American community seem not a part of mainstream America. I would never imagine the Japanese government coming here (to speak for the Japanese-American community). The Japanese-American response to them would be, you’re not welcome.

--Jimmy Tokeshi, 30, Japanese-American civil rights activist, reacting to Korean self-defense and Korean government officials’ visit to L.A.

Koreans are not like we are. Most are (immigrants) from Korea and want to keep among themselves. That will cause a problem.

--Roy Yokoyama, 70, Japanese-American senior citizens center administrator.

Vietnamese are kind of bystander victims, like in a drive-by shooting. (People) don’t know the difference between Koreans and Vietnamese. Some Vietnamese defendants in drug-related cases were attacked by blacks in jail because they were mistaken for Koreans. We don’t like Japanese. Japanese invaded Indochina and in 1944-45, 1 million Vietnamese died of hunger. . . . Cultures and economies are different. Japanese say (to Chinese): “Your ducks hanging in the restaurant are dirty, you should refrigerate it like my sushi.” It’s not a necessity to get together. I don’t think we need it. It is too soon to think of the Asian community as one. It’s too impossible. Maybe the young ones can.

--Hoang-Ha Thanh, 55, Vietnamese-born businessman .

After the riot a black man walked into my brother’s store. He asked the price of beef. Then he said: “You Koreans charge too much.” My brother said: “I’m not Korean, I’m Cambodian.” But he’s mad. He says: “You Koreans rip us off.”

When I saw something gone like (my store that was burned down)--I feel like unconscious. I never think it’s going crazy like this. It’s a very strong country. I still like the U.S. very much.

--Samath Yem, 41, Cambodian-born store owner.

We know the importance of networking and coalition-building (with other Asian-Americans). But most people in the community don’t care about that. To them the question is how to pay the bills. We (Cambodians) are not in good shape, we’re not a healthy community to start with in terms of mental well-being. During the riots a lot of people experienced flashbacks.

--Vora Kanthoul, 46, Cambodian-born community organizer .

A lot of the tensions that exist between (Asian) communities are historical. . . . There is anti-immigrant feeling. It is easy to finger-point in a time of crisis.

--Phyllis Chang, 33, Korean-American museum educator.

I saw two reactions (among Asian- Americans): Some people supported us and realized the only way to survive is to solidify; (but) there are some trying to make Korean-Americans separate from other Asian-American groups. Some say: “I don’t want to be mistaken for a Korean-American.” I was very sad. My parents’ generation has no contact (with other Asian-Americans). My father can’t speak English. He can’t get a job even though he graduated from college in Korea. His only option is to do business. Now, Koreans are used as sacrificial lambs for the problems of mainstream society. The problem was really between white and black people. We (Koreans) don’t have power, but we’re used as a group in the middle to pay for the problems of society.

--Hee Choi, 32, Korean-born son of a grocery store owner whose store was burned during the riots.

What my community has felt is that the focus has been on Koreans and blacks and a lot of assistance and attention has gone to their needs. We’ve felt out on our own. I don’t consider myself an Asia-Pacific Islander, though people have put us in that category.

We’ve been lumped within that category. For me, I’m a Filipino and that’s it. We have to be particular we’re not counted as Asian in affirmative action situations.

--Caroline Lorenzo, 42, Filipino-American computer systems manager.

Of course, I admire how Koreans came together. We (Filipinos) are too scattered. For us, it’s very easy to integrate. Maybe that’s why we can’t be solid. Sometimes I go to a store and since I’m not Korean I feel out of place. They’re not friendly to people who are not Korean. It happened to me, too; maybe blacks take it more personally.

--Vangie Tan, 35, Philippine-born shop owner and office worker whose store was burned down during the riots.

Chinese business people are afraid to rebuild. They don’t trust the police anymore. Rich people are too rich. Poor are too poor. It’s like a (time) bomb.

--Derek Ma, 39, Chinese-born owner of a construction business.

In South-Central and Long Beach, people don’t know if you’re Korean or Chinese. (But) Chinese are friendly to (local people). That is how overseas Chinese can get along everywhere. Overseas Chinese (who have been merchants around the world for many generations) have more experience in how to handle a bad situation (than Koreans).

--Jee Chin, 61, retired Hong Kong-born engineer.

The so-called Korean-black conflict has been so overexploited there’s almost a self-fulfilling prophecy. Problems are out of the control of either group to solve. We both don’t control the justice system. Both groups ask for help and don’t get it. . . . I was working on a civil rights case once in North Carolina. A white waitress asked: “Where are you from?” I told her my great-grandfather came to work the mines in New Mexico. My grandfather was a tailor in Oakland and my mother was born in Stockton. And the waitress interrupted and without any hesitation said: “So how do you like your new country?”

--Stewart Kwoh, 43, Chinese-American civil rights activist.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.