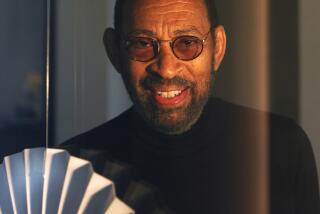

Saving the Last Dance : Friends Honor Legacy of Tap Master and Teacher Eddie Brown

- Share via

Old masters and young phenoms brought their tap shoes and memories to Los Angeles’ Ebony Showcase Theater on Wednesday to do “the Eddie Brown,” a dance chorus named for the generous genius who died of cancer last week at 74.

They remembered Brown, a master of rhythm tap improvisation, as an innovator who--unlike most accomplished dancers--was more than willing to teach them each new step as it came whirling from his imagination.

“He wanted to give you his best steps because he would forget it in five minutes anyway,” one student said. “The only way to preserve an Eddie Brown step was in somebody else’s memory.”

Some tap dancers could do eight bars, or maybe 16, but Brown “could do dance after dance after dance, and it just rolled out--this beautiful rhythm,” said Los Angeles dancer Fred Strickler.

Strickler once asked Brown if he ever got lost in the midst of all those complex rhythms he created.

“I get lost all the time,” Brown said. “Sometimes I didn’t know how I would get out. But I just trusted my feet.”

Brown began trusting his feet on the streets of Omaha where he was born and began dancing. At 16 he met “Mr. Bojangles” himself, Bill Robinson, and brashly demonstrated a pilfered Robinson routine. He later toured China with Robinson before launching a solo career in the 1930s.

After World War II, the demand for tap dancers virtually disappeared, so Brown taught himself piano and scraped by as a musician. But even leaner years were to come, and Brown waged twin battles against poverty and alcohol.

He had come from a generation of unappreciated geniuses, black performers who toiled for the sheer love of their craft and art because they were not offered the contracts that might have come their way had they been white.

“The steps you saw from Eddie Brown were not merely dance steps--they were the sounds of survival,” said Paul Kennedy, master of ceremonies at Wednesday’s memorial. “A lot of times he would do a step in hopes of getting a sandwich--or a job. Those moves were very, very serious.”

Kennedy, who teaches tap at his sister Arlene’s Universal Dance Designs studio in Los Angeles, said Brown and many other great black dancers “knew they were good. They got jobs, but they didn’t get what they should have for being as good as they were.”

Eventually, the attention came with the resurgence of tap, Kennedy said, and it came from many of the people in the theater on Washington Boulevard on Wednesday.

In the mid-1970s, Brown resurfaced as lead tap dancer in “Evolution of the Blues,” a San Francisco production that featured black entertainers.

He may have found fame elusive, but his genius was abiding. Soon the word was out about this man whose style was described as dancing “close to the floor” and who did things with his heels that other tap dancers found astonishing.

Tap historian Rusty E. Frank, who met Brown during those San Francisco years, said: “His complex rhythms were his greatest contribution to tap. He was willing to sit down with kids and pass on his material. A lot of old-time dancers didn’t want you to use their routines.”

Brown moved to Los Angeles in 1982, continuing to teach, perform and occasionally tour.

“He had a unique style,” said Arthur Duncan, a tap soloist on the Lawrence Welk Show for 20 years. “He was an exponent of close rhythm dancing--rhythmic patterns as opposed to leaps and jumps.”

Dance teacher Arlene Kennedy said Brown described everything he did as “scientific rhythm.”

“He said he found how he could cut the tempo of the music in half and double the rhythm of the steps,” she said.

Actor Nick Stewart, 81, a remarkably agile tap artist who runs the Ebony Showcase, described Brown as “just a master dancer. It was a thrill to watch him. Just makes chills go through you.”

His friends remembered his personal style as much as his dancing on Wednesday, fondly recalling his Stetson hat, his glasses falling down across his nose, his enthusiastic greetings and the accolade he extended when someone correctly performed a step: “Outta sight.”

As he battled the cancer that would take his life, Brown insisted on teaching his classes on Saturday mornings, and he depended on his students to keep the sessions organized and running.

“We just loved him,” Lillian Hill, one of his students, said Wednesday. “He was a terrific man. He had it to give and we took.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.