Breakthrough in Sickle Cell Treatment Reported : Medicine: Biomedical therapy shows dramatic results in initial tests. Disease affects 50,000 U.S. blacks.

- Share via

In a step toward a “biochemical cure” for sickle cell disease, two teams of researchers report that they have developed a simple and relatively safe treatment for the disorder, which affects about 50,000 blacks in the United States.

The technique also was successful with another disorder, beta-thalassemia, which like sickle cell disease involves defective hemoglobin in red blood cells. In addition, researchers say that if follow-up tests are successful, it could have potential implications for certain types of cancers.

Researchers reporting in today’s New England Journal of Medicine say they have devised chemicals that trigger the activity of a hemoglobin gene that normally functions only in fetuses, becoming dormant after birth. The healthy fetal hemoglobin replaces defective adult hemoglobin, and in the small number of patients in the study alleviated virtually all the symptoms of sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia.

“The results are very exciting and dramatic,” said Dr. Douglas V. Faller of Boston University Medical School, head of one of the teams. “In every case, the patients treated for even this short period of time achieved levels of fetal hemoglobin that would be predicted to completely alleviate their disease.”

The results in two patients have been so good, in fact, that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration gave the researchers a compassionate waiver to continue treating them even though the safety trial was scheduled to end after three weeks.

But the discoverer of one of the new drugs, Dr. Susan P. Perrine of the Oakland Children’s Hospital, cautioned: “These results look very promising, but they must be confirmed in larger trials with longer time courses to see what the full potential is.”

The treatment could have potential implications far beyond these two diseases, however. Using similar approaches, researchers might, for example, be able to activate tumor suppressor genes that would halt the growth of cancer.

“This may be the first example of a whole new type of therapy for genetic diseases in which drugs are designed to regulate gene expression,” Faller said.

The results represent “very encouraging news,” said Dr. Kwaku Ohene-Frempong of Philadelphia Children’s Hospital, president of the National Assn. for Sickle Cell Disease. “My real hope is that some larger studies can be organized as soon as possible.”

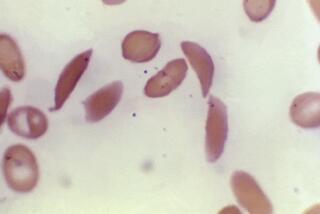

Sickle cell disease is caused by a simple defect in the gene that serves as the blueprint for beta-hemoglobin, the red cell component that actually carries oxygen throughout the body. In times of physical or emotional stress, the defective red cells assume a sickle shape and clump together, blocking the passage of blood through small capillaries and drastically diminishing the body’s supply of oxygen, causing tremendous pain and organ damage, which can eventually lead to incapacitation or death.

Beta-thalassemia, caused by a different defect in beta-hemoglobin, affects no more than 10,000 people in the United States, most of them of Mediterranean descent, but it strikes millions worldwide. Because of the defect, beta-hemoglobin is not produced and the victims become severely anemic.

Beta-thalassemia patients must receive constant infusions of blood, which leads to a toxic overload of iron that ultimately proves fatal.

For reasons that are still not clear to scientists, fetuses use a different form of hemoglobin. Researchers have long speculated that an ideal therapy for both sickle cell disease and thalassemia would be to stimulate production of this fetal hemoglobin in adults by “turning on” the gene that controls it.

For several years, physicians have been able to stimulate some production of fetal hemoglobin with an anti-cancer drug called hydroxyurea. But they have been reluctant to use it widely because it can cause cancer in continued high doses. Its use is limited in children, furthermore, because the necessary high doses suppress bone marrow development and may affect growth.

Dr. Griffin P. Rogers and his colleagues at the National Institutes of Health report today that they were able to increase production of fetal hemoglobin in four patients while reducing the dosage of hydroxyurea. They achieved this by combining it with iron supplements and erythropoietin, a naturally occurring hormone that stimulates red cell production.

Using this combination, they increased the percentage of fetal hemoglobin in blood from its normal 1% to 2% level to a high of 78%. The combination sharply reduced sickling and the associated pain suffered by the subjects, although Rogers cautioned that it is too early to determine whether it will reduce the damage to organs. NIH is sponsoring trials of the regimen at five centers around the country.

Another promising approach involves a drug called arginine butyrate, developed by Perrine. Arginine is one of the 20 amino acids from which all proteins in the body are produced, while butyrate is a fatty acid that is commonly found in dairy products.

Perrine discovered the drug after she observed that children born to diabetic mothers produced fetal hemoglobin several weeks longer than other children. Eventually she found that the continued production seemed to be the result of an above-normal level of butyrate in the infants’ blood.

Subsequent studies in sheep, chickens and primates showed that arginine butyrate could stimulate production of fetal hemoglobin, prompting Perrine and research partner Faller to test it in humans. They infused the drug into the blood of six hospitalized patients--four with sickle cell disease, two with beta-thalassemia--daily for three weeks in a test designed primarily to show only safety.

One of the patients had a “complete reversal” of her disease, Faller said. “Looking at her blood, you would not know that she had thalassemia.” The other five also showed significant improvement, with the production of fetal hemoglobin increasing by as much as 45%.

The team has already begun second-stage trials in Oakland and elsewhere to demonstrate the effectiveness of the infused drug. They have also begun safety trials of a new formulation developed by Perrine that can be taken orally. “We have 20 other medical centers who are waiting for FDA approval to begin trials of the drug,” she added.

Even so, the trials are proceeding slowly, Perrine said, because the team has received no backing from a drug company. “They want to make $100 million to $200 million profit a year, or they won’t make (a drug)” she said. As a consequence, all the arginine butyrate used in the trials is still made by a tedious process in her laboratory.