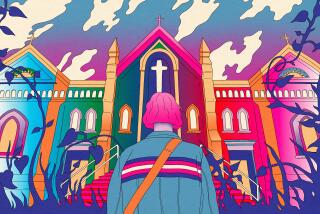

Children of Change : New names. New holidays. New rules. Youths accepting Islam face a lifestyle conversion.

- Share via

As the muezzin at the Islamic Council of Southern California begins the 1,400-year-old chant of the adhan, the slow, deep, long vowels of the Arabic call to prayer, the men of the Al-Haneef family already are kneeling at the front of the mosque.

Other worshipers remove their shoes and pad over the soft tan carpet. Men move to the front and women to the back, not disturbing the reverie of white-robed Bilal Ali Al-Haneef and his sons, Hassan, 13, and Jahmaal, 11, who are facing Mecca with their heads bowed.

The boys have no trouble remembering when during the prayers to stand, when to kneel and when to bow their heads to the floor in obeisance. But sometimes they struggle with their Arabic pronunciations because they have only been saying the prayers since November, when they joined their father in accepting Islam. Their mother followed within a month.

“When I did the prayer with my father over Thanksgiving, I felt a lot better about myself,”Hassan says of his decision to become a Muslim. “I thought it was the right thing to do. All the time Allah is on my mind now. Everything I do now has something to do with Islam.”

Although exact numbers are difficult to assess, most experts estimate that 4 million to 7 million Americans practice Islam, believed to be the fastest-growing religion in the country. And of the roughly 25,000 Americans who convert to Islam each year, says Fareed Nu’man, director of the department of research for the American Muslim Council in Washington, more than 90% are African-American.

African-American parents have been introducing their children to Islam since the early part of the century when Marcus Garvey called on them to forge ties with their African past. The trend continued with the Nation of Islam, founded by W.D. Fard in the 1930s and led for a time by Malcolm X, although the majority of conversions today are to orthodox Sunni Islam.

As more adults turn to Islam, they bring increasing numbers of children into the faith with them. At Masjid Bilal, a mosque in South-Central Los Angeles, the imam , or spiritual leader, says he has 50 or 60 adult converts annually, which can add 100 to 200 new children each year.

For the children of converts, a mid-childhood change to new names, new holidays, new rules, new friends and often a renewed family bond can mean a different path toward accepting--or not accepting--Islam for themselves.

“Islam does not create any more problems than Judaism or converting to Christianity,” says Maulana Karenga, chairman of the black studies department at Cal State Long Beach. “It depends upon how it’s introduced and how the parent makes the person feel--greater by it, more important by it, more achieved by it, or confined and constricted by it.”

*

The Al-Haneefs’ Watts-area home is immaculate; it is the boys’ responsibility to keep it tidy.

The chocolate-colored carpet still shows vacuum lines. Off-white floral-patterned couches are spotless. A stack of books, including Part 30 of the holy Koran, “The Prophets’ Stories for Children” and “Science: The Islamic Legacy,” is neatly piled on the coffee table.

At meals, after a brief word of thanks to Allah for the bounty, Bilal Ali Al-Haneef adds: “Thank you for making us Muslims.”

Bilal, who had been Earl R. Driver Jr. for 45 years, pledged his faith to Allah last October. He chose his new name carefully: Bilal was the first muezzin of Mohammed, the first man to call the believers for prayer. Ali means honorable, and Al-Haneef means one who forsook the path of many gods for the path of one God, he says.

A month after their father’s conversion, the boys, who were given Muslim first names at birth in spite of being baptized Roman Catholics, told their mother that they wanted to abandon her faith.

“All I could say was, ‘Are you sure this is what you wanted to do?’ ” Raashidah Al-Haneef recalls. “They said it felt good to them. All I could say was Allah knew best--at that time, it was God knew best.”

The day after Thanksgiving--Nov. 27, both boys recall--Hassan and Jahmaal took shahadah ; they affirmed their belief that there is no god but Allah and that Mohammed is his messenger.

“Once a family decides to convert to Islam, you’re really talking about a different way of life,” says Hakim Rashid, an associate professor of human development at Howard University’s School of Education. “The potential problems have a lot to do with the age of the children and how much the children have internalized and identify with the dominant culture.”

Rashid adds, “If a family converts to Islam and they have an adolescent son or daughter who has a boyfriend or girlfriend, they would be expected to give that relationship up, because the concept of dating does not exist in the Islamic lifestyle.”

Converts must also accept Islam’s dietary rules, which means no pork or alcohol; restrictions on explicit language, which can mean staying away from certain types of music, movies and television, and dictates about modest dress.

“Remembering the rules is the hard part,” Hassan explains. “It’s all the time they’re telling you something and you’re, like, ‘Oh, man, another rule? How many rules are there?’ ”

In fact, there are rules that govern just about every part of a Muslim’s life, Rashid says. And although Rashid warns about “ruling children to death,” Hassan and Jahmaal are eager to learn as much as they can about their new faith in spite of their occasional frustration. When he cannot answer a question himself, Hassan races to get one of the family’s many books on Islam. Jahmaal listens intently while his brother reads the text aloud.

“I’m happy that I’m Muslim because we pray and I like the Koran--it’s nice to read,” Jahmaal says. “I like the way they explain stuff to you.”

Walter Allen, a UCLA sociologist and an expert on African-American families and child development, holds that religious adherence to any faith is often beneficial for families, and therefore for the children.

“We recognize that with many religious conversions and religious commitments comes some very positive returns in terms of how families feel about themselves, how they interact and how individual members feel about themselves,” Allen says.

“The kinds of values that are emphasized (in Islam)--a personal discipline, a commitment to achievement, a positive self-esteem--can be part of rearing children who are productive, disciplined, honorable citizens guided by a strong moral code.”

To explain the changes in their children after Islam, Bilal gestures toward them. “The depictions of teen-agers today, it’s not this,” he says. The boys, neatly dressed with shirts tucked in, heads covered in the traditional knit skullcap, or kufi , sit straight and silent while their father speaks.

Raashidah adds that her boys are still boys, however. They still sometimes forget to clean their rooms. Jahmaal still needs to work harder in school. They still need reminders on certain household rules, she says. But their attitudes are different.

Both boys talk about the changes in their lives: Hassan no longer talks back in class because Islam teaches him to respect his teachers, he says proudly. Jahmaal, who was labeled “dysfunctional” by the Los Angeles Unified School District, his father says, has raised his grades from Ds and Fs to Bs and Cs.

“We usually just sat down and watched television before,” Jahmaal says. “Now we read more.”

If the transition to Islam has been easier for the Al-Haneefs than some others, it has not been effortless.

Because Raashidah and Bilal believe the boys’ Catholic school is the best local option, there are no plans to move Hassan and Jahmaal to Islamic schools farther away; the boys will continue to use their old last name there and jog around religious assignments that they can no longer fulfill. Both boys have been teased about their new faith by classmates.

Hassan says he misses his friends from church. And Jahmaal says he sometimes has trouble with his new schedule of praying five times a day, especially because the first prayer is about 4 a.m.

Jahmaal adds that in spite of the two Muslim Ids , or feasts, when he received gifts from his family, it was still hard during the Christmas season to watch other children play with new toys. Late-afternoon prayers can also be difficult, both boys agree.

“Sometimes, like when we have to go in and pray, it’s when all your best friends are coming out to play,” Hassan says. “And we still have to come in and pray.”

Rashid, who is also the author of “In Search of the Path: Socialization, Education and the African-American Muslim,” says the greatest obstacle for most Muslim children is relationships with their peers.

He says those children sent to non-Muslim schools face overwhelming pressure to behave “like the other kids.” Child converts to Islam may face additional difficulties because of their stronger ties to secular people and secular life, he notes.

Entia Lawal, now 23, converted to Islam with her family nearly two decades ago. She remembers growing up with a vague idea about a girl named Phyllis Durden. It wasn’t until years later, when she asked her grandmother, that she learned that Phyllis was her own name before she converted.

Her first years in Islam were fun, she says, and learning Arabic was like learning the language of a secret club. But attending public school in the Los Angeles area was particularly difficult.

“The kids were cruel to me because I was Muslim and dressed differently,” Lawal recalls. “I wanted to fit in. I thought I would fit in better if I wasn’t Muslim, so I told my father that I didn’t want to be Muslim.”

But after abandoning her faith in high school and searching for a new faith throughout college, Lawal returned to Islam and married a Muslim.

“(My father) seemed more hurt than angry,” Lawal recalls about telling her father that she was leaving Islam. “He said, ‘Now that you know what’s right, you really can’t get away from it.’

“He turned out to be right. I’m back.”

*

While they recognize that some parts of the conversion may be difficult for their children, Bilal Ali and Raashidah Al-Haneef feel that the bond created between them and their children is more than enough to compensate. The boys say they agree.

“We’re more attentive because the fabric of the family is a lot tighter,” Bilal says. “Prayer pulls us together at key points in the day. I see the unity in prayer as an intensification of our love.”

Just after sunset at the Al-Haneefs’ home, Bilal motions for his sons to unfurl their prayer rugs. The family forms a diamond shape facing the northeast, toward Mecca. Bilal stands in front, the two boys set up next to each other and behind their father, and Raashidah unrolls her rug behind the boys.

Bilal chants the call to prayer. His sons close their eyes, then stare straight ahead, deeply focused. They respond to their father’s chant with Allahu Akbar, God is most great. The boys’ faces show their concentration: eyes straight ahead, mouths expressionless. They do not flinch when, at 9 p.m., their digital watches break into the melodic rhythm of the Arabic prayer with short, electronic beeps. Jahmaal struggles to contain a yawn, then finally gives in.

At the end of the prayer, each member of the family touches the head, the heart and the mouth--to signify “in the mind, the heart and everything we speak about you”--and says, “May the peace and blessing of Allah be upon you.” Both boys smile.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.