Konitz Plays Tribute to Mentor : Jazz: The saxophonist, a leading figure of the ‘cool school,’ studied theory and improvisation under pianist Lennie Tristano, whose legacy is celebrated at the Hyatt Newporter tonight.

- Share via

Sometimes great things come of chance meetings. So it was when a young Lee Konitz, playing tenor sax for a dance band in his hometown of Chicago in the ‘40s, happened across the street to hear a Latin jazz orchestra. In that ensemble was a blind piano player named Lennie Tristano.

“I was very impressed with his playing,” Konitz recalled earlier this week by phone from his home in Manhattan. “I sat in and played with him, and we got together and talked afterward. I realized from talking to him that he could help me a lot with my music.”

And Konitz, with a touch of understatement in his voice, added, “I think he did.”

Konitz, who joins fellow saxophonist Gary Foster tonight at the Hyatt Newporter to honor the music and the spirit of Tristano’s legacy, went on to become the pianist-composer’s best-known disciple.

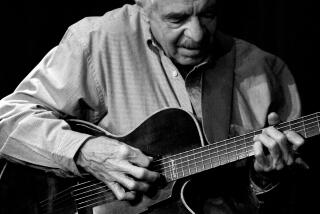

As a leading figure in the so-called “cool school” of jazz, a form that roughly developed concurrently with the hot, be-bop style, Konitz, playing alto, went on to become every bit as influential as his mentor Tristano, who died in 1978.

“Bill Evans once said it wasn’t Lennie Tristano that had the greatest influence on him--it was Lee Konitz,” Foster confirmed. “That’s a very powerful thing, for a saxophone player to influence someone who plays all the harmony (on piano). It’s usually the other way around.”

Born in 1927, Konitz in 1947 joined the legendary Claude Thornhill Orchestra, an ensemble that served as a spawning ground for many of the principle cool-school figures. It was there that the saxophonist met Miles Davis, leading to his participation in Davis’ landmark nonet recordings of 1948-1950 that came to be known as “The Birth of the Cool” sessions.

It was also around this time that Konitz, looking to expand his musical sensibilities, met Tristano.

“He was playing music like I’d never heard before,” said Konitz, “very substantial stuff, very strict, very disciplined kind of music. It was just what I needed for my educational makeup.”

The saxophonist joined an elite circle of musicians working with Tristano that included fellow saxophonist Warne Marsh and guitarist Billy Bauer.

What were their studies like?

“Generally, (Tristano) addressed basic theoretical information and philosophy and playing: the music, things in general on the planet, very elementary stuff. He was concerned that we knew the basic information that applied to the playing of a song. We were dealing with the standards and the possibilities for extending them and taking them wherever we wanted to take them.”

Tristano, who had received classical training early on, expanded the harmonic aspects of his proteges’ playing while widening their sense of improvisation.

Much of the clean, direct, technically astute style that has come to be associated with Konitz derives from this classical influence. But the all-inclusive improvisational style that is also associated with this music came from a hunger to explore their instruments’ frontiers.

“What makes that improvising so strong,” said Foster, “is that it’s spontaneous music, a lot of chances are taken. And Lee is one of the people who have continued that part of the art form and brought it forward. He was never afraid to take chances.”

Like the members of the be-bop movement, Tristano’s students were adept at taking the chord changes of well-known tunes and adapting them to serve their purposes.

“There’s a tradition of adapting standards,” explained Foster. “Charlie Parker wrote tunes, Dizzy Gillespie wrote tunes that fit the changes. (Konitz’s) famous tune ‘SubconsciousLee’ is based on Cole Porter’s ‘What Is This Thing Called Love?’ The beauty of the original composition is what has attracted people to it and that’s why it’s stayed alive over the years.”

While some critics have written that the cool school developed as antithesis to the bop movement, neither Konitz nor Foster sees it that way. But staying out of Parker’s shadow presented a problem.

“I was trying to dodge that bullet all along,” Konitz said. “I didn’t let myself listen to (Parker’s) music all that much at the time. He was the definitive saxophonist, but I didn’t want to be assuaged by his playing.

“What we were doing was adding new material to the bop cannon, doing it in a white-man’s way, whatever the differences that implies--culturally, environmentally, economically. That’s been an issue right along. A lot of whites apologize for playing the black people’s music, but it’s all--white and black--basically theme and variation on a theme. Still, whenever I play a blue note I feel guilty.”

To some, the idea that Konitz feared being overly influenced by Parker seems absurd.

“Lee was a completely original voice when Charlie Parker showed up and shook the world,” said Foster, “and he’s continued to be his own voice throughout the years. He continues to be a very youthful and vital guy.”

“I’m very active now,” confirmed Konitz, “more than ever and in good health. I enjoy playing a lot now that I have seniority rights.”

His recent itinerary confirms it: Earlier this month he was in Europe to play with drummer Paul Motian’s forward-looking ensemble, which includes tenor saxophonist Joe Lavano and kinky electric guitarist Bill Frisell.

Also this summer, he recorded what he calls “a very ambitious recording” that includes different pairings with Motian, pianist Paul Bley’s trio with clarinetist Jimmy Giuffre and bassist Gary Peacock, singers Helen Merrill and Judy Niemack and baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan.

“There’s even a free-form duet with (trumpeter) Clark Terry on which we both sing, something called ‘Mumbles and Jumbles,’ ” he said.

At 57, Foster, too, is very active. Concord has just released a live duo session with keyboardist Alan Broadbent (a late scratch from tonight’s Hyatt concert). Foster can also be heard on the soundtracks to “Coneheads” and “Another Stakeout” as well as the latest recordings by Natalie Cole and Barbra Streisand.

Though he did not study with Tristano, Foster said that he feels his influence through the powerful effect that Konitz has had on his playing. And Tristano’s influence continues to be felt by the latest generation of musicians.

“Someone just told me that a lot of the younger musicians are now discovering Tristano,” Konitz said. “It’s a classic story of the cyclical nature of things. People always come around eventually to something of value.”

* Lee Konitz and Gary Foster appear with pianist Cecilia Coleman, bassist Putter Smith and drummer Paul Kreibich tonight at 7:30 at the Hyatt Newporter, 1107 Jamboree Road, Newport Beach. $15. (714) 729-1234.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.