Stop the Presses: Papers Enter a Brave New World : Media: Electronic visions sharpen. Mergers, advances push publishers onto the ‘information superhighway.’

- Share via

NEW YORK — When Roger Fidler first laid out his ideas for an electronic newspaper back in 1981, he got “absolutely no response.” Seven years later he tried again, outlining his high-tech vision to newspaper executives at the American Press Institute.

But the presentation “fell flat,” he said. “They thought it was all Buck Rogers stuff.”

It wasn’t until last year that Fidler’s company, the Knight-Ridder newspaper chain, agreed to finance his research on the newspaper of the future. The Knight-Ridder Information Design Laboratory in Boulder, Colo., is a modest operation--just seven people--but it’s a start.

All across the newspaper industry, companies that long have resisted the information revolution are beginning to act. With phone companies, cable operators and computer firms spending billions of dollars in hopes of creating an “information superhighway,” newspaper executives fear that unless they do something soon, they’re going to be left behind.

The $33-billion merger of Bell Atlantic Corp. and cable powerhouse Tele-Communications Inc., announced a little more than two months ago, was a jolt for those who suspected that the information highway was so much hype. Newspaper companies, which never have invested much in research and development, now have to figure out where they fit in a world of 500-channel TV systems and ubiquitous personal computers.

“Up to this point, I could defend the decision not to spend money on these new technologies,” said David Easterly, president of Cox Newspapers Inc., which publishes the Atlanta Journal and Constitution and other papers. “But now is the time to establish some turf in (electronic services). Others will do it if you don’t.”

Newspaper publishers--including Cox, Knight-Ridder, Times Mirror Co. (parent of the Los Angeles Times), the Washington Post Co. and the Tribune Co.--are all pressing ahead with a variety of electronic information services, including versions of their newspapers for customers who own personal computers.

Yet much of the activity reflects the uncertain instincts of an industry that, in the words of veteran newspaper analyst John Morton, “has always reacted rather than innovated.” Few companies have committed significant resources to electronic news services. And even some of the more ambitious efforts appear to be based on a highly traditional view of what readers and advertisers want.

*

“There’s a lot of scrambling to look like you’re doing something,” says Gary Hoenig, editor of the industry publication News Inc. But he said he is not sure that newspapers have figured out yet how to deal with new technologies--or are prepared to spend serious money on them.

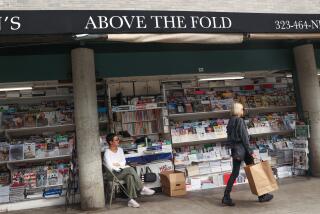

In some respects, the caution is understandable. Skeptics note that the traditional newspaper is cheap, light, portable and disposable. Products that require a personal computer or other electronic hardware do not share those characteristics.

The skeptics were proven right in the early 1980s, when Times Mirror, Knight-Ridder and their partners lost at least several million dollars on electronic information services known as Videotex.

The technology, based on a special terminal that plugged into television sets, was crude by today’s standards.

And some say not all that much has changed.

“At this point, you’d have to say there is no compelling demand for the information a newspaper provides to be transmitted in electronic form,” said Hunter George, vice president of Toronto-based Thomson Newspapers, which owns 112 small papers in the United States. “People prefer the printed word. They do not like to read off a TV.”

Yet advances in computer and communications technology have made it possible to create electronic information and entertainment services that are far richer, cheaper and easier to use than Videotex. These advances have spurred an unprecedented wave of mergers, strategic alliances and business start-ups in every corner of the media business, as companies position themselves for the Age of Interactive Multimedia.

*

Many newspaper companies also own cable television operations, and the cable businesses are in many cases the focus of their new technology investments. But the newspapers are also now getting attention.

Tony Ridder, president of Knight-Ridder, says it is only necessary to look at the sales figures to see that newspaper companies need to think in new ways. The industry has been mired in a severe advertising slump for several years, and Ridder said he suspects that it is not just a cyclical decline.

“1990 was flat, but in 1991 revenues fell--it was the worst year-to-year comparison ever,” he said. (The Miami-based company enjoyed a slight rebound in 1992.) “That really hit us square in the face. There was something going on out there, and we decided that instead of hunkering down, we would start working on new ways of delivering things.”

To see the underlying economic logic of electronic delivery, one need only look at a modern newspaper printing plant, such as The Times’ new facility in downtown Los Angeles.

The $230-million Olympic Boulevard press building, which covers nearly 1 million square feet, turns 430 tons of newsprint and 700 gallons of ink into 600,000 newspapers every day--newspapers that are then delivered across the Southland by hundreds of trucks.

It is enormous manufacturing and distribution operations like this--rather than the salaries of reporters or editors or advertising salespeople--that account for the majority of expenses at The Times and other major newspapers. The cost of duplicating such an infrastructure has kept many potential competitors out of the news business.

But this Industrial Age method of delivering information is expensive and inflexible. To print different papers for different parts of Southern California, for example, is very costly. To customize the paper for individuals is downright impossible, though so-called zoned editions are serving smaller and smaller geographic areas, and some papers are moving toward editions targeted to subscribers with specialized interests.

Electronic distribution, by contrast, is highly flexible. It makes it possible to offer a much richer variety of information--the full texts of political speeches, for example, or the complete roster of every high school football team--with individual customers selecting only what they want.

To the degree that electronic delivery allows newspapers to reduce the amount of paper they deliver, they can chop their costs. For the most part, though, experts say electronic services won’t be replacing newspapers so much as augmenting them. “The newspaper business is in transition from a single-product business to a multiple-product business,” Fidler said. “Newspapers will publish things in many different ways.”

Many papers already publish in more than one way. In Los Angeles and elsewhere, newspaper-sponsored telephone services provide weather reports, sports scores, stock quotes and much more. Cox’s Atlanta Journal and Constitution has set up a joint venture with Bell South, the local telephone company, to deliver classified ads over the phone.

Newspapers, including the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times, have started special fax editions that can deliver customized financial news or reach readers in far-off locations. Specialized electronic information services for businesses--such as those offered by Mead Data’s Lexis/Nexis or Dow Jones & Co., publisher of the Wall Street Journal--have been growing rapidly in recent years.

However, the big challenge isn’t these services but the launching of broad-based consumer services that use dial-up computer networks, wireless communications services and the upcoming interactive television networks.

At Knight-Ridder’s San Jose Mercury News, one such system began operating a few months ago in conjunction with America Online, a national personal computer network. Customers can dial in from their personal computers and read the daily paper, view articles from past issues and get additional information--including original documents--about the day’s news.

They can also send messages to reporters and editors, peruse the classified ads or look up where their favorite rock band is playing--all with a few clicks of the keyboard. The newspaper itself prints codes at the end of stories and other instructions to help people navigate the online service.

Bob Ingle, executive editor of the Mercury News, calls the project “an experiment that we hope will turn into a business.” He said it will be two years before it is possible to evaluate the results, but it has already become clear that there is demand for in-depth information relating to news stories: That’s been the most popular category on the service.

*

The Tribune Co., which owns a 10% stake in America Online, recently launched a similar service with the Chicago Tribune. The Tribune Co. is pursuing what analysts call a “buckshot” approach to new technology--trying many different ventures in the hope that a few of them will work. It paid $57 million for Compton’s New Media, a publisher of multimedia computer disks, and acquired a company in the Washington, D.C., area that has developed an electronic system for real estate advertising.

The Washington Post Co. last month launched a new subsidiary, dubbed Digital Ink, to develop electronic products, including a computer-linked version of the newspaper.

And Times Mirror announced in August that it will develop electronic versions of its newspapers--beginning with the Los Angeles Times and Newsday--in conjunction with Prodigy Services, an online service jointly owned by IBM and Sears Roebuck & Co. Cox also opted to go with Prodigy.

The deals raised some eyebrows, for Prodigy has lost prodigious sums of money since it was launched, and critics contend it uses cumbersome, outdated technology. America Online, a smaller and newer venture, had wooed Times Mirror heavily, sources say.

But Prodigy, unlike America Online, will allow Times Mirror papers to retain complete control of the service. Rather than being one option among many on an online service, The Times and Newsday services will be completely separate. They’ll use the Prodigy network, but customers will buy the service independently and dial up on a different phone line, with existing Prodigy customers likely receiving a modest discount.

*

The graphics capabilities of Prodigy will also make it possible to offer display advertising across the bottom of the computer screen. America Online is not designed for such advertising.

“We want the newspaper to have as close a connection as possible to the customer,” said Chip Perry, director of new business development at Times Mirror. “We thought it was important to have a fully branded service and control as much of our own destiny as possible.”

Yet not everyone is convinced that it is a good idea for newspapers to seek the same level of control in--and the same sources of revenue from--electronic services as they’ve enjoyed with print.

“That’s taking an old metaphor--which sold advertising by adjacency to news--and transferring it to a new medium. It won’t work,” said Ingle of the Mercury News, whose Mercury Center service now only runs text-only ads but eventually will offer interactive sales. “We’re moving toward a time when there will be less reliance on advertising, and it will be more informational and more targeted.”

Trying to predict how--and how quickly--electronic news services will evolve is, of course, extremely difficult.

For example, while Times Mirror and the Mercury News believe that PC-based online services will be a good business, others say electronic information services won’t have wide appeal until people can tap into them with a remote control and the television set. Prodigy, America Online and other services are all preparing to make themselves available over interactive television systems once the cable TV and telephone companies get such networks up and running, possibly later in the decade.

Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. bought Delphi Information Services earlier this year. However, the company’s priority is not an electronic version of its New York Post but a customized, worldwide electronic newspaper for executives on the go.

Dow Jones is also targeting the mobile executive with a news service called the Personal Journal, which will be available next year via hand-held “personal communicators.”

Even Fidler is a bit of a skeptic on personal computer-based services. He’s counting on the emergence of lightweight, inexpensive, high-resolution computer screens--he calls them “tablets”--to create an entirely new vehicle for news distribution.

*

This new kind of electronic tablet, Fidler said, will resemble paper more than a TV set. “We’ve been trying too hard to force document technology into video technology. Documents have evolved over a period of time, and they have certain standard characteristics. . . . You have to give people the ability to read them wherever you happen to be--in bed, on a train, in a coffee shop.”

With Fidler’s tablet, you’ll be able to tap a headline to get a story, a photo or even a video clip of the event in question. Touch the small advertising symbol and you’ll get a screen full of promotional information--and maybe be able to order the product on the spot.

But one need not dispute Fidler’s vision to question how important his notions about electronic news are for business today.

The New York Times Co., for one, remains convinced that the print newspaper will be its key business for many years to come. It recently made a big acquisition--the venerable Boston Globe.

“Right now, there is no consumer market for electronic services. . . . The consumer perception is that we’re still in the Videotex age,” says Gordon Medenica, vice president for operations and planning at the Times Co.

Medenica said the New York Times is one of the few papers that earns significant profits in online services, via its relationship with Mead Data Central. Nexis pays royalties in exchange for the rights to back issues of the newspaper.

*

But when the deal was signed 12 years ago, the Times gave Nexis the rights in perpetuity. Medenica concedes that he would feel better if the contract had an expiration date. Recently, though, the Times Co. signed an agreement with America Online to offer access to the same day’s newspaper.

Ultimately, the real challenge for newspapers will be to design a whole new model for the electronic world. Self-contained news stories will be augmented--or even replaced--by layers of stories, with levels of detail. Pictures and graphics will move. Display advertising will give way to electronic buying and selling.

Analysts say newspapers, with their extensive news gathering organizations, editing skills and recognized brand images, have a big leg up in building this new generation of information services.

But their expensive printing and distribution operations won’t be a defense in the electronic world. They’ll have to defend themselves with creativity instead.

“Quality newspapers . . . are well-equipped to succeed in the shifting media world,” Shelby Coffey III, editor of the Los Angeles Times, said at an investment conference in Scottsdale, Ariz., this fall. “They’ll succeed because of their attention to basic reader psychology and because they understand the key transformation of turning information into readily graspable knowledge.”

* RELATED STORY: A14

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.