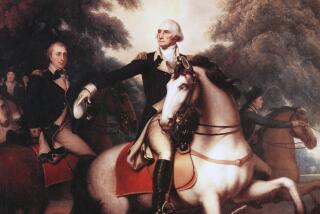

BOOK REVIEW / SCIENTIFIC HISTORY : Can Disease Explain Our Leaders’ Actions? : WAS GEORGE WASHINGTON <i> REALLY</i> THE FATHER OF OUR COUNTRY? A Clinical Geneticist Looks at World History, <i> by Robert Marion, M.D.</i> Addison-Wesley. $22.95, 206 pages

- Share via

In 1928, Alfred Kroeber, founder of the anthropology department at the University of California, Berkeley, proposed a fascinating theory of culture, which he called “the superorganic.”

Still hotly debated, his idea--in greatly oversimplified form--goes something like this: every act, every choice has, ultimately, some impetus from a previous experience. This process applies both to individuals and to large, interrelated societies.

We are all, in other words, the products of our personal and our collective histories, and if every scrap of data were fully known (which, of course, it never can be), there should emerge a rational explanation for what otherwise might be termed accident, whimsy or even free will.

Most scientists generally subscribe to this doctrine, inasmuch as their systematic search for answers is based upon the presumption of a logical order in the universe. Reason, more than fate, is regarded as the common denominator of modern existence.

Dr. Robert Marion operates very much in this tradition. In his intriguing new book, “Was George Washington Really the Father of Our Country?” he attempts to retroactively diagnose possible genetic maladies in six key historical figures and to suggest how these diseases might have impacted upon Western history.

Why, for instance, did England’s King George III suffer periodic bouts of seeming insanity, and how did this problem affect the outcome of the American Revolution? The monarch suffered from an inherited form of porphyria, Marion tells us, which caused episodes of unpredictable pain, irrationality and loss of function. But for these incapacities (which can be traced both in the king’s ancestors and royal descendants all over Europe), would the Colonies have succeeded in achieving independence?

And here’s a stunner: Napoleon, who late in life seems to have gained a lot of weight and developed what can only be described as breasts, may have indeed been motivated to conquer the world because of an inferiority complex--but not stemming from what most people think.

Perhaps he spent too much time alone as a child and maybe he was ashamed due to what one researcher euphemistically terms “organ inferiority.” But what do you know? He wasn’t short! It turns that an Austrian historian, not understanding that the French of that time used a different standard of measuring height, got confused about the not-so-little general’s size and the error has been glibly repeated to this day.

Marion writes in a clear, conversational style that draws us in, and before we know it, even we English-major types are, against all odds, comprehending erudite scientific terms and theories. He educates, as do most fine teachers, by telling us a story that allows us to painlessly digest multisyllabic arcana--in this case having to do with enzyme malfunction and genetic irregularity.

In the process, we not only learn impressive anecdotes with which to regale our friends at the next neighborhood barbecue, but we finish his book--don’t be put off by the unwieldy title--feeling a bit smarter about all those biochemical terms that have long intimidated us.

Yes, along the way Marion set us up for a few too many red herrings: After basically convincing us that Abraham Lincoln looked as physically disjointed as he did because he had a joint-connection problem, Marion informs us that this probably wasn’t the case. Lincoln was, apparently, simply gawky.

But even the speculations that don’t go anywhere definitive are interesting, because they illuminate the methodology and rationale of any attempted medical sleuthing, past or present.

“Having settled upon a diagnosis,” Marion writes, “the next question that must be asked is: What difference does any of this make? . . .

“What really must be determined is whether the presence of the features of a particular genetic disorder actually played any role in the formation of the character of the man who came out of the Illinois wilderness in early 1860 as a virtually unknown lawyer and, on a platform that supported his inherent belief that slavery was morally and ethically wrong, was elected President of the United States.”

This issue is particularly relevant in the book’s final section, which deals with John F. Kennedy. Marion persuasively argues that the very determination J.F.K. exhibited and honed early in his life in overcoming a serious physical ailment (he had a spinal problem known as Addison’s disease) “reinforced Jack Kennedy’s feeling that he was invincible, that he could accomplish any goal.”

In such accounts, Marion weds science and history into a compound that provokes thought even as it stimulates curiosity.