Clinton, Cabinet Open Drive Against Assault Weapons : Legislation: Effort seeks enough support to have the measure included in talks reconciling House, Senate versions of the crime bill.

- Share via

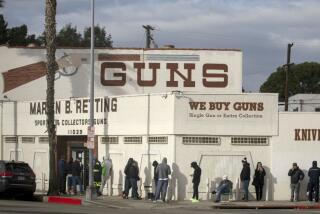

WASHINGTON — President Clinton and Cabinet officials inaugurated a campaign Monday to revive a proposed ban on assault weapons, an issue that has broad public support but a woeful legislative record because of opposition from the gun lobby.

Acknowledging the long odds against them, Clinton, Atty. Gen. Janet Reno and Treasury Secretary Lloyd Bentsen opened a series of public events by appearing with relatives of victims of mass slayings. Supporters of the ban say they must convert 15 to 20 members of the House of Representatives to win a floor vote and put the issue before the congressional conferees who will soon meet to iron out differences in the House and Senate versions of the crime bill.

“It’ll be an all-out, uphill battle to win this one,” Bentsen conceded in a Rose Garden ceremony. The Senate legislation includes a ban on the weapons.

Some polls show Americans favor the idea of a ban by margins of nearly three to one; and some surveys have suggested that even a majority of staunch conservatives want to prohibit such military-style weapons.

But congressional showdowns have proved humiliating for advocates, and even the 1991 mass slaying of 23 persons at a Killeen, Tex., cafeteria only narrowed the gap in the House by one vote, with a proposed ban failing by 70 votes.

Rep. Jack Brooks (D-Tex.), chairman of the House Judiciary Committee and an opponent of the ban, has agreed to put the issue to a floor vote again because he is confident it will fail, sources say. Brooks, who is joined by House Speaker Thomas S. Foley in his opposition, applied his influence to keep the ban out of the overall crime legislation in the House so that the issue could be voted on separately.

Helping fuel opposition to the ban is the fear some members of Congress have about casting a second vote against the National Rifle Assn. Over NRA objections, Congress voted earlier this year for the so-called Brady bill, which established a minimum five-day waiting period on handgun purchases. California already had a 15-day waiting period.

“A lot of members are saying, ‘We voted against the NRA once--we just can’t do it again,’ ” said one House aide.

Still, the bill’s advocates maintain that public sentiment for a ban should be strong enough to overcome gun lobby opposition, provided sufficient attention is focused to the issue. “There’s movement,” said Rep. Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.), a leading advocate.

The Rose Garden ceremony included remarks by Steven Sposato, whose wife, Jody, was among the eight killed when a gunman opened fire last year in a San Francisco law firm. Sposato, a Republican, described the devastating impact on his life.

“The sight of our 10-month-old daughter, Megan, putting dirt on her mother’s grave is a sight and a pain I hope no one, no one ever experiences,” he said.

Bentsen said such assault weapons made up only 1% of guns in circulation in the United States, but accounted for 8% of the guns traced by the authorities to crimes. “If you’re a criminal, if you’re a drug kingpin, if you get your kicks by drive-by shootings, wouldn’t you want the tool that could produce the most carnage?” he asked.

Bentsen said that two years ago, when he was in the Senate, his vote in favor of a ban brought thousands of letters opposing his decisions. But he said most of those came from “special interests that generated that mail.”

In his comments, Clinton told of meeting an immigrant hotel worker during the 1992 election who said that though his family had more money in America than in their former home, they were not free because their 10-year-old son was afraid to play in the New York City park across the street from his home. “Freedom is an empty word to people who are not even gifted with elemental safety,” Clinton said.

The proposal’s advocates say that if the floor vote in the House fails, the measure still has a chance to be considered by the conference committee, since it was included in the Senate bill. But they acknowledge that those chances would be much slimmer.

A survey by the Los Angeles Times poll last December showed that 71% of Americans favor banning the future manufacture, sale or possession of rapid-fire assault weapons. Of that group, 58% said they favored the idea “strongly.” Twenty-four percent said they would oppose the measure. Even among respondents who described themselves as “very conservative,” the measure was favored by a margin of 58% to 34%.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.