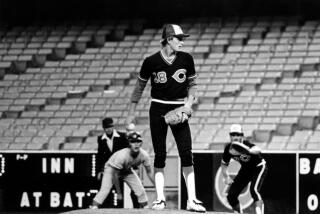

His Own Man : Jaret Wright Is Proud to Be Clyde’s Son but Ready to Establish a Separate Identity

- Share via

ANAHEIM — Jaret Wright wiped the sweat from his brow, stood upright and inhaled the deepest breath of his young life as the firing squad took aim last August in San Diego.

The setting was the annual Area Code Games, an event designed to help professional scouts and college recruiters in their search for young baseball talent. Wright was an especially hot item during the four-day window-shopping extravaganza in which the top players in the class of 1994 showcased their stuff.

Talent evaluators raised their radar guns in unison each time the Katella High pitcher prepared to throw. And like any good salesman, Wright continually made the right pitch.

He dazzled the crowd at San Diego State’s Smith Field and forced the baseball experts--men not easily wowed--to do double takes at their speed guns’ numbers.

In fact, Wright unleashed a crackling fastball that traveled consistently at 94 m.p.h. So impressive was Wright that many of the guys with the guns believe he might head the class of high school pitchers selected in the June amateur draft.

Just the way he planned it. Ah, well, sort of anyway.

“I was so nervous,” Wright said. “I’ve never been in a situation like that before--tons of scouts, tons of coaches and your destiny in your own hands.

“There must have been 30 or 40 scouts behind the plate watching me. It was like a must-win situation, and walking away knowing you did your job is a great feeling.”

The son of former Angel pitcher Clyde Wright, Jaret possesses tools that might help him become a pitching force in his own right. He hopes his blazing fastball will help him light a path out from behind his father’s long shadow.

Word of Wright traveled as swiftly as one of his pitches.

“Jaret is one of the best pitchers in high school this year,” said Joe Ingalls, an area scout for the Chicago White Sox. “He throws real hard, and not many kids throw hard these days.”

Longtime Esperanza Coach Mike Curran believes Wright has as much raw talent as any high school pitcher he has seen.

“I don’t remember anybody who threw as hard as he does with the curveball that he’s got,” Curran said. “And none of the other guys were the athlete he is.”

Based in large part on his smashing audition in San Diego, and because of the praise of those who witnessed the performance, Baseball America ranks Wright as the fourth-best high school prospect in the nation. Agents, recruiters and scouts have the Wrights’ home phone number on speed-dial lists.

It seems that everyone wants a piece of the action. Even Sports Illustrated came calling.

Jaret was pictured in the magazine’s “Faces in the Crowd” section May 2. He was all smiles of course, just the expression one would expect from someone who at 18 seemingly has the world hanging on every flick of his wrist.

“When that Sports Illustrated came out, it was really kind of amazing,” Wright said. “I mean, this is a national magazine that you’re in as high school player.

“I’ve been looking at that thing for so long, so it’s strange actually thinking you’re now in one.”

Along the path to celebrity, Wright has been the focus of good-natured barbs from coaches and teammates.

“When the Sports Illustrated thing came out, Coach (Tim McMenamin) said, ‘He’s big-time now,’ ” Wright said. “My buddies say stuff like, ‘Can I have your autograph?’

“But it’s all been playful. Everybody has a good time with it.”

Such scrutiny and time demands can be taxing for most families. For the Wrights, however, it’s commonplace.

“This is not unusual around here,” said Vicki Wright, mother of five children. “It’s really nice that this is happening with Jaret because I’m so used to dealing with this with Clyde.”

Clyde is one of the Angels’ all-time pitching leaders.

He signed with the Angels in 1965 and reached the big leagues a season later. Clyde pitched for the Angels until 1973, and is fifth on the club in career victories (87).

Clyde had his best season in 1970, finishing 22-12 with a 2.83 earned-run average. He is one of only five Angel 20-game winners, joining Nolan Ryan, who accomplished the feat twice, Dean Chance, Andy Messersmith and Bill Singer.

He pitched for Milwaukee in 1974, Texas the next season and in Japan for three seasons (1976-78) before retiring with a major league record of 100-111 and a 3.50 ERA. Clyde works for the Angels in community relations and runs a pitching school in Anaheim.

Clyde and Jaret are a father-and-son no-hitter tandem--albeit their feat is separated by more than two decades and several levels of baseball.

As an Angel in 1970, Clyde no-hit Oakland in a 4-0 victory. Jaret no-hit Laguna Hills in a 7-1 victory March 6.

Watching his son’s development brings to mind fond memories.

“I don’t think he realizes exactly where he’s sitting,” Clyde said. “He’s got good mechanics and he throws pretty darn hard. That’s something a lot of people are looking for.”

Funny thing is, though, Jaret wasn’t sure he had it in him.

Jaret said the velocity on his pitches had not been measured until the Area Code Games. Of course, he figured he threw hard--just not that hard.

“I had no idea,” he said. “I never thought about that stuff. I don’t stand (on the pitching mound) and think, ‘What did this scout say, or what was (the reading on) the gun.’

“As soon as you say, ‘I’m going to try and throw this hard, or do this to impress this guy,’ is when you have problems. If you keep focused on the game, all that other stuff will come.”

Clyde said Jaret’s arm strength did not come from his father’s genes.

“He must have got that from his mother’s side,” Clyde said, jokingly. “Heck, I never got it up there at more than maybe 85, 87 (m.p.h.).”

Jaret credits his father, God and football for his velocity.

Clyde did not break out the radar gun during his tutoring of Jaret, instead opting to focus on the technical points of his son’s delivery. Also, Jaret participated diligently in an intense weight-training regimen during his four seasons in Katella’s football program. Jaret was the starting quarterback on the varsity the last two seasons.

At 6 feet 2 and 220 pounds, Jaret said he can bench press 250 pounds. The work in football paid off in increased arm strength.

“I also have to thank God for giving me the gift of a strong arm,” Jaret said. “If it was just something you could teach, then everybody would have one.”

Jaret credits his father for not turning baseball into something unhealthy. He said Clyde was the antithesis of those “Little League fathers” who push their kids so much they come to hate the game.

“There is enough pressure from school and playing baseball, so not having to come home and worry about what my dad would think really helped,” Wright said. “When I was doing something bad, I knew I could ask for help. Instead of yelling at me from the stands, my dad was always there for me.”

However, for all the help Clyde provides, he is also a source of frustration for Jaret. Being the son of a former major leaguer does not come without its difficulties.

“Having your dad looked at as a public figure in baseball and then you come up having some baseball talent makes people expect things,” Wright said. “I’ve had stories about me in the paper during football season that said, ‘Jaret Wright, the son of . . .’ I mean, my dad never even played football.

“It’s something I’ve just had to learn to deal with.”

Clyde has counseled Jaret on how to change the situation.

“I told him I’m going to be his father until I die, and he’s going to be my son until he dies,” Clyde said. “So what he has to do is get good enough so people start saying, ‘Look, there goes Jaret Wright’s father.’ ”

The process is in motion.

A co-captain for the Knights, Wright finished the regular season 7-2 with a 2.98 ERA. He pitched Katella to a share of the Empire League championship--its first baseball title since 1981--by shutting out Cypress, 5-0, in the regular-season finale Thursday.

What’s more, he struck out 13 batters to reach 100 (in 75 innings) and lead the county in that category. Wright is skilled at the plate, too. Third in the Knights’ lineup, Wright batted .430 with seven home runs and 32 runs batted in.

Last season, Wright’s first on the varsity, he was 4-3 with a 3.01 ERA and 80 strikeouts. He hit .451 with seven home runs and 26 RBIs.

While his pitching numbers are less than prodigious, people who make baseball decisions are unfazed.

“That doesn’t matter,” said Chuck Menzhuber, an area scout for the St. Louis Cardinals. “When you’re looking at guys, you have to project how they will be three or four years from now.

“You have to picture them at 20 or 21 and try to figure how good they’ll be then. He’s far along in terms of how hard you need to throw.”

College recruiters are of the same mind-set.

Wright has scholarship offers to play baseball at BYU and UCLA.

But if he is a high draft choice, he can expect an immediate financial windfall. Just like dad.

“I signed for $10,000 in 1965, and I was on top of the mountain,” Clyde said. “I thought I had all the money in the world.”

Signing bonus money, of course, is a little better today.

First-round draft choices last season signed for between $355,000 and $1.3 million. The first high school pitcher selected in the 1993 draft, Kirk Presley, was taken by the Mets with the eighth overall pick and signed for $900,000.

The money that players are offered depends on numerous variables, such as how high they are selected, by whom and if they have the added bargaining leverage of college scholarship offers.

The Wrights have not discussed how much money it would take for Jaret to head for the minor leagues. No matter the course he takes, his mom believes one thing has changed for good.

“I’ve spent a big part of my life being Clyde Wright’s wife,” Vicki said. “And now it looks like I’m getting ready to be Jaret Wright’s mom.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.