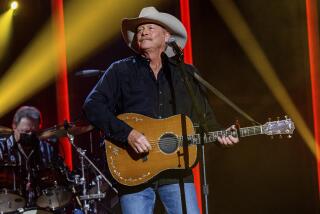

POP MUSIC : A Country Boy on a Hit Streak : Shy, gentle Alan Jackson is no Garth Brooks and doesn’t want to be. ‘I like makin’ records and singin’ and writin’ songs,’ he says. ‘Other than that, I’m not really that crazy about the award shows.’

- Share via

Garth Brooks’ massive record sales in the ‘90s have overshadowed what is, in its own right, one of the most remarkable hit streaks ever in country music.

Alan Jackson’s 1990 debut album, “Here in the Real World,” has sold 2 million copies. The follow-up, “Don’t Rock the Jukebox,” passed the 3-million mark, and 1992’s “A Lot About Livin’ (And a Little ‘Bout Love)” has reached 4 million.

The new one, “Who I Am,” should bring him close to a grand total of 10 million before long--a bit short of Brooks’ 30-million-plus, but impressive enough. Jackson’s singles haven’t done badly either. The current “Summertime Blues” is his 14th No. 1 country single.

But Jackson, who plays the Greek Theatre on Wednesday, is no Garth Brooks--and he doesn’t want to be.

“Just recently, TV Guide had a picture of Alan and it said, ‘Garth’s Worst Nightmare,’ ” recalls Gary Overton, a longtime friend of Jackson’s who became his manager in March. “Alan looked at the story and he looked at me and said, ‘Boo. Do I scare you? I don’t believe I scare Garth either. I’m never gonna be Garth, and I don’t want to be.’

“He really would like to pattern himself after a George Strait,” Overton continues. “We do our music, we do our shows, and we do a few interviews, but that’s pretty much it. He said, ‘Everyone’s kind of lookin’ at us right now to take that big spotlight out there because Garth’s not really doin’ anything. But it’s not me.’ ”

That’s putting it mildly. Where Brooks is flamboyant, driven and in-your-face, Jackson is low-key and relaxed, striving to balance career demands with his family life. He’s not given to grand gestures or controversy, and he plays it straight and simple on stage. When pressed for an opinion, he’ll preface it with an elaborate apology, as if afraid of offending someone, or unable to comprehend why people would be interested in his views. And instead of cultivating celebrity with a high profile, he heads for the hills at every opportunity.

Jackson escapes from the music and its business by holing up with his wife and two daughters at their home in Center Hill Lake, Tenn., keeping his distance from both guitar and telephone.

He tries his best to avoid country’s social swirl. When Overton took over his management, Jackson asked if maybe he could get out of co-hosting the Academy of Country Music Awards telecast (it was too late, so he presided, a game but never-quite-comfortable master of ceremonies).

“The people that work for me call me a hermit,” says Jackson, 35. “I just don’t really like the star part of the business. I like makin’ records and singin’ and writin’ songs. Other than that, I’m not really that crazy about the award shows and all the things that jab into your personal life. . . . I guess I’m just kind of introverted. I really like people. I’ve just always been that way.

“My wife, this is exciting for her, to come out here to Los Angeles. She can go shoppin’ and all that. And me, I’d rather just be at home foolin’ with my cars or up at the lake doin’ somethin’.”

*

Sitting in his Universal City hotel suite, Jackson seems almost painfully shy. With a 6-4 frame and fine features, he resembles some exotic land bird as he gazes out the window at hills where cowboys once rode and soldiers fought for Hollywood’s cameras. Another escape.

“I love old movies, old actors . . . ,” he says softly. He becomes gradually more open as the interview proceeds, but never fully dispels his reserved manner.

“John Wayne, people like Jimmy Stewart and Gary Cooper. I could sit here and name ‘em all day.

“I see biographies about some of the older actors, they remind me of some of the singers I’ve been talkin’ about, Hank Williams and them. They came from rural backgrounds, and all of them went into World War II and they came out of that and . . . they end up out here in the movie business. They had lived , and they were real people when they walked onto the screen.”

This kind of rich sense of nostalgia flows directly from Jackson’s childhood just outside the town of Newnan, Ga., where he and his four older sisters grew up in a house that was built around an old tool shed. His grandparents had divided their acreage among their children, so there were other relatives on adjacent plots. It was a poor but close-knit upbringing.

“We were like the Waltons kind of,” he says. “The family and all my cousins lived around us, my grandmother lived next door. I feel like sometimes I grew up in a time warp where I was 30 years behind other people.”

That rural and small-town life would later provide the material for Jackson’s biggest hit, 1992’s “Chattahoochee,” a warm account of adolescent, waterfront high jinks. At the time, though, he had no idea he’d ever write or sing.

Jackson and his wife, Denise, a schoolteacher, were both young when they married. Jackson worked a series of jobs, including driving a fork lift at a K mart, and began playing with a band in local clubs. When he started going to see name acts at a new country music park nearby, he got hooked.

“I decided, ‘I’m gonna move to Nashville and just give it a try.’ A buddy of mine said he was gonna be an airplane pilot . . . and the next thing I know he was workin’ for American Airlines.

“You know, he had a dream and he went for it and he made it. I said I need to at least give mine a shot. I’d never been to Nashville, or hardly anywhere. I told my wife I wanted to sell everything and move, and everybody thought I was crazy.”

*

That looked like a reasonable opinion five years later, after he’d been rejected by every record company in town. He was ready to pack it in when one final batch of demos and a live showcase led to a contract with Arista Nashville.

“I don’t know why everybody passed, but I do know why I signed him,” says Tim DuBois, president of the label. “I saw in him a unique writing talent, coupled with an identifiable voice. There was just an honesty in what he did and who he was that I thought would work.

“He’s not a Vince Gill, he’s not a Garth Brooks and he doesn’t try to be,” continues DuBois, who wrote several country hits himself before becoming an executive.

“I love songwriters and love songs, and in Alan there was a simplicity in what he did and what he said as a writer that really attracted me. He hadn’t been in Nashville so long that he had been polluted by the way we Nashville tunesmiths write things. . . . He still was doing things a little bit different. It was neat and it was fresh.”

If Jackson’s life seems devoid of conflict and drama, there was at least that first unsettling year of stardom, when the suddenly accelerated pace turned his lifestyle upside down, making him rich and famous while yanking him away from family and friends.

“It’s just a lot to swallow,” says Jackson. “I think I got kind of caught up in it there for a while.”

But it didn’t take long for him to sort things out.

“I didn’t grow up with a guitar in my hand, I didn’t live and breathe music,” he says. “I love this job and have been real successful at it, but I don’t commit my whole life to it. I have to have my family and I have to have my personal life, and that’s what I finally realized there after a year.”

Says Arista’s DuBois: “Obviously nobody can sell 10 million records and win 20 major awards without it affecting you in some way. But when the foundation is there of a good person, someone who is very humble and who realizes where he came from--he’s really still the same shy, gentle, but very strong-willed person that he was in the beginning.”

Associates say that Jackson is both more mischievous with friends and more assertive in business dealings than his reserved manner would indicate, with a keen sense of his audience and the direction of his career.

Jackson pauses when asked to name the key turning point in his career. He finally singles out the end of his struggle for a deal in Nashville, when he made his set of winning demo recordings. In previous attempts, he had let producers tell him what songs to cut and how to sing them. This time, he got Keith Stegall, the producer he’d been after, and he got it right.

“They were my songs, and I finally cut my songs the way I wanted to do ‘em, and that’s what got the attention of the label. I tell people now when they ask me, I say, ‘Do what’s in your heart and don’t let people change you. Do what you want to do.’ ”

* Alan Jackson plays on Wednesday at the Greek Theatre, 2700 N. Vermont Ave., 7:30 p.m. $15.50-$32.50. (213) 480-3232.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.