Cover Stories : Hendrix, the Grateful Dead, the Eagles and dozens of other artists both popular and obscure have been saluted by tribute albums. But is this a trend that’s already run its logical course?

- Share via

For a business not renowned for etiquette, the music industry seems obsessed these days with saying thank you.

The sentiment comes in the form of tribute albums, wherein an often diverse group of contributors shows its respect for an artist by respectfully recording his or her songs.

Neil Young, the Grateful Dead, Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan, Tom Petty, Prince, KISS, Van Morrison and the Eagles have been saluted this way, along with Curtis Mayfield, Woody Guthrie, Merle Haggard (twice), George Gershwin, Richard Thompson, Edith Piaf, the Carpenters and Lynyrd Skynyrd. On the way: tributes to John Lennon, Led Zeppelin, Blondie, Buddy Holly, New York Dolls guitarist Johnny Thunders and Harry Nilsson.

Can a tribute album honoring tribute albums be far away?

“We started talking about our record a year ago, and we had no idea there was going to be this great gob of tributes coming out,” says Dave Konjoyan, who organized the 1994 Carpenters tribute, “If I Were a Carpenter,” with Matt Wallace. “But I don’t have a problem with it. Tributes galore--great. If it’s a good album, it’s a good album. If it’s not, it’s not.”

The current round of tribute albums began almost entirely on small, independent labels in the late ‘80s. They were directed at specialized, often underground tastes.

“The Bridge,” a 1989 Neil Young tribute, was typical of the somewhat innocent, low-key celebrations of artists who had deeply influenced a younger generation of musicians. Though prized by cultists, the album--featuring heartfelt versions of Young songs by such cutting-edge acts as Sonic Youth and Nick Cave--failed to crack the national Top 200 sales charts.

Producer Hal Willner served as something of a pioneer in crafting tributes, bringing together during the last decade-plus a wide range of artists for albums that honored the music of jazz great Thelonious Monk, Kurt Weill and film composer Nino Rota. He also tapped such diverse talents as Sun Ra, the Replacements and Bonnie Raitt to celebrate the music of Disney films on “Stay Awake.”

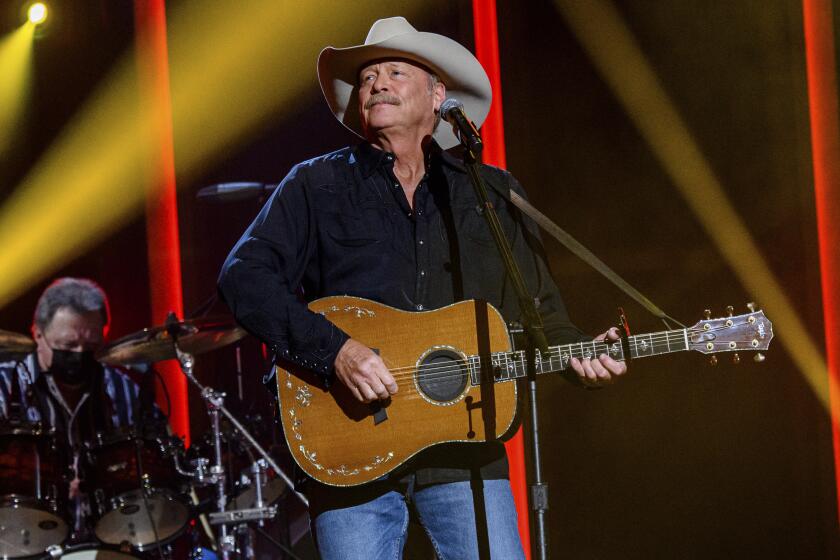

Today, contributors still often approach tributes with a fan’s enthusiasm, but many of the records have become high-profile endeavors. “A Common Thread: Songs of the Eagles,” the 1993 album featuring country stars singing Eagles songs, and Frank Sinatra’s two self-tribute “Duets” albums have sold into the millions.

Those collections, however, are the exceptions. Sales of other major-label tributes last year ranged from less than 20,000 for “No Prima Donna: A Tribute to Van Morrison” to about 150,000 for “If I Were a Carpenter” to more than 550,000 for “Stone Free: A Tribute to Jimi Hendrix.”

“I thought ‘Common Thread’ was going to do well, but I didn’t know it was going to be huge,” says James Stroud, president of Giant Records in Nashville and executive producer of the album, which has sold about 3 million copies.

Stroud, however, warns against trying to duplicate the album’s success: “If it keeps going like it’s going, tribute albums are going to run their course fairly quickly.”

Larry Hamby, who is vice president of A&R; at A&M; Records and who oversaw the work on the Carpenters tribute, agrees.

“It’s a time-honored record business tradition,” he explains. “If something works, by God, we’re going to keep repeating it until we embarrass ourselves.”

At the moment, the embarrassment factor hasn’t set in. There seems to be no shortage of tribute-paying celebrants or salute-worthy stars. Even with the abundance of tributes in production, the records are still taken quite seriously by both contributors and subjects.

That doesn’t mean that a first listen to a tribute can’t be a little nerve-racking for the honoree.

“I carried it with me for a few days without playing it and finally put it on with some trepidation,” says Tom Petty. He’s talking about “You Got Lucky,” a 1994 tribute package featuring underground bands punking up a mix of his hits and obscure tracks.

But he was pleased:

“The most flattering thing was that it was young and unsigned bands. I was touched that they did it, and that they did it so well. I’ve played the record again and again, until I’ve finally had to declare a moratorium on my listening to Tom Petty songs.”

The San Diego band aMiniature covered Petty’s “Century City,” and the group’s singer-guitarist John Lee says contributing to the album was a particular pleasure. “When you go from being a seventh-grader with a ‘Damn the Torpedoes’ poster in your room to being able to record one of the songs--it’s fantastic.”

Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley of KISS were so pleased when Australian and Norwegian fans put together KISS tributes the last couple of years that they decided last year to oversee one of their own.

“We weren’t going to sit around and wait for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame,” Simmons says. “We decided to throw our own party.”

The aggressively titled “KISS My Ass” featured such artists as Garth Brooks, Lenny Kravitz and Dinosaur Jr. retooling KISS hits. Estimated sales since its release last summer: about 300,000 copies.

“A song is never just a song,” Simmons says. “And that includes KISS songs. You’ve got to put your stamp on the music, or else you may as well be playing in a bar. I was floored by the creative versions of our songs that were turned in. I’m still excited about the music on this record.”

Simmons believes that tribute albums should be celebrations of the music’s spirit rather than its significance:

“The problem is in asking, ‘What does this music mean?’ Get a grip. It means nothing. ‘KISS My Ass’ means nothing. It means we’ve had a good time, we’ve written a few good songs, and some other people liked them.”

But he does believe that the tributes can demonstrate the important connections between established rockers and newcomers.

“The only real story in our tribute is that it’s showing off the graduation class of our fans--the KISS Army,” he says. “The fans have become the band. Kids like Garth Brooks and Lenny Kravitz saw KISS onstage and thought maybe they could do that too. But if they’re giving credit to us, I’m pointing to the Beatles, because without Lennon and McCartney, I wouldn’t have done what I did.”

Simmons and Stanley played “traffic cops” for their tribute--personally inviting the bands they wanted for the record and keeping track of song assignments. Van Morrison took that approach a step further, going into the studio with artists such as Elvis Costello, Marianne Faithfull and Sinead O’Connor to produce last year’s “No Prima Donna: The Songs of Van Morrison.”

Other artists believe that it’s better not to be involved at all in their tributes. John Chelew, the concert producer at McCabe’s Guitar Shop in Santa Monica, organized and produced “Beat the Retreat,” a tribute to respected songwriter and guitarist Richard Thompson that features performances by Bonnie Raitt, R.E.M., David Byrne and Los Lobos. Estimated sales: about 30,000.

“I met with Richard a couple of times before I started the record,” Chelew recalls. “He said, ‘I’m glad you’re doing this, but I’m so particular about my music that no matter what you do I probably won’t like it. Do it in your own way and don’t try to please me.’

“He mentioned a couple of singers he detested that he hoped I wouldn’t use, but other than that he said, ‘Go for it.’ That totally freed me--he let me off the hook to do some experimenting.”

Deciding on how far to stretch the music of another artist is often a difficult call for tribute album contributors. Los Lobos has had some practice at matching its skills as a band with the strengths of someone else’s song--the group has contributed to the Thompson album and a Grateful Dead tribute and has recorded for the forthcoming Doc Pomus and Johnny Thunders albums.

“It’s a challenge,” says Los Lobos singer-guitarist David Hidalgo. “You want to treat the song with respect and do it justice, but at the same time, you don’t want to copy it. You want to do something a little different without losing the original feeling. That’s a little tricky.”

D espite the willingness of musi cians to give and receive trib ute, pulling an album’s worth of reinterpreted tracks together can still be very difficult.

“The amount of red tape is amazing,” Chelew says. “For each track on a tribute, it’s about the amount of red tape you’d go through for one regular album. The first record I worked on was John Hiatt’s ‘Bring the Family,’ which took four days to do. ‘Beat the Retreat’ took four years. It was like going to college.”

That won’t stop Chelew from tackling more tribute projects--maybe even a second volume of Thompson music.

“I’d love to do it,” he says. “The music’s out there, so why not use it? In jazz, you hear dozens of versions of the same standards, so why not dozens of versions of a great Richard Thompson song or a great Elvis Costello song? It’s just a matter of putting the song first. It’s the folk process--it’s all about recycling, rephrasing and reintroducing meaningful music to a new audience.

“We just need a better phrase than ‘tribute album.’ Tribute assumes too much. What if it’s terrible? It’s an album first, and if it works maybe it’s a tribute.’*

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.