Drug-Resistant Bacteria Pose an Increasing Threat : Health: About 13,000 die in U.S. each year from germs that have developed a tolerance for common antibiotics.

- Share via

The middle-aged woman was desperately ill. Brought by an anxious daughter to the emergency room at St. Joseph Medical Center in Burbank, she was nearly in a coma, her brain swelling with meningitis.

Doctors swiftly put her on two antibiotics that for years have been highly effective against the disease. But she failed to improve, and lab tests showed she had a form of meningitis that resists both drugs.

As precious hours ticked by, physicians finally switched to one of the last lines of defense in the antibiotic arsenal, vancomycin. Still the woman got sicker. After five days in the hospital, she died.

“It’s kind of an impotent feeling,” said Dr. Alan Morgenstein, a Glendale infectious disease specialist and one of the physicians who tried to save the woman. “You know what’s going on but you can’t do anything about it.”

Half a century after the medical breakthrough of penicillin, antibiotics are losing their almost miraculous power to heal pneumonia, meningitis, tuberculosis and other dangerous infections. The medications are being thwarted by “superbugs”--bacteria with the ability to resist antibiotics.

An estimated 13,000 Americans die each year from drug-resistant bacteria, while others who survive face lengthy hospitalization and treatment with more expensive, more toxic drugs. And experts warn of the likely emergence of an untreatable “Andromeda strain” that could touch off epidemics in hospitals and other facilities.

“Antibiotics are very rapidly slipping away as a strategy to combat infectious diseases,” said Dr. Stephen Ostroff, associate director of the National Center for Infectious Diseases in Atlanta.

“Once we lose the ability of antibiotics to treat infections, we’ll certainly see a resurgence of these diseases,” he said. “You just have to think back to how things were a century ago. A lot of infections caused a lot of fairly severe complications when they weren’t treatable, including death.”

Consider:

* Pneumonia, which each year kills an estimated 1 million people worldwide, including 25,000 Americans, is becoming steadily more resistant to penicillin, an inexpensive drug that kept it at bay for more than five decades.

* Mutant forms of tuberculosis, which has resurged sharply in the United States in recent years, can resist as many as 11 drugs and has become a major threat to people who also have the AIDS virus, hastening their deaths.

* Millions of American children suffer from inner-ear infections often caused by drug-resistant microbes, at a cost of billions of dollars in lengthy treatments and parents’ lost wages from repeated trips to the doctor.

* The first reported outbreak in California of a vancomycin-resistant intestinal bacteria last year prompted ominous warnings from health officials that the germ could pass its drug-fighting genes to a far more dangerous bacteria that could cause perhaps thousands of deaths in the state.

Antibiotics still can knock down most infections in most people, experts say. But in a growing number of cases, bacteria can withstand multiple drugs. In some instances, germs cannot be stopped by any medicine.

“The number of deaths in humans due to drug resistance is going to get worse before it gets better,” said Dr. Stuart B. Levy of Tufts University Medical School in Boston, author of “The Antibiotic Paradox: How Miracle Drugs Are Destroying the Miracle.”

Since 1942, when a new drug called penicillin saved scores of victims burned in a Boston nightclub fire, antibiotics have been hailed as the greatest therapeutic discovery in history.

Before such drugs, hospital wards were packed with people--most of them young--doomed to chronic complications or early death from pneumonia, typhoid fever, meningitis, tuberculosis, rheumatic fever, syphilis and other bacterial ailments.

Antibiotics quickly cured or controlled such illnesses. Indeed, so complete was the drugs’ victory that U.S. Surgeon General William Stewart urged researchers in 1969 to “close the books on infectious diseases” and concentrate on still deadly maladies such as cancer.

But bacteria have dramatically stiffened their defenses in recent years.

*

Although resistance went up only slowly through the 1960s, some bacteria began developing strong resistance in the 1970s. In the 1980s, strains appeared that were resistance to two or more drugs. Today, some TB strains can withstand as many as 11 drugs. And resistant mutants have spread to virtually every nation.

In parts of Africa, 50% of the bacteria that cause cholera--a severe form of diarrhea that often is fatal in the Third World--are resistant to tetracycline. In Spain, Eastern Europe and Central America, some pneumonia strains can resist penicillin and three other antibiotics that were once standard treatments.

Resistance is a particularly severe problem in developing countries, where older antibiotics are widely used and more advanced drugs are unaffordable. While a shot of penicillin costs less than $1, newer drugs can cost $100 a day.

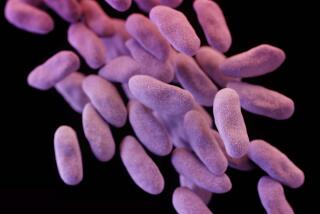

Composed of single cells, bacteria are among nature’s simplest organisms, as well as its hardiest. They thrive in places that would destroy most other life forms, from the iciest peaks of the Himalayas to heat-belching vents at the bottom of the sea.

Attacked by drugs, some bacteria die while the “fittest” survive in a microscopic Darwinian process. Each time germs live through an antibiotic assault, they gain resistance.

Because bacteria can exchange genetic material, one microorganism can pass drug-resistance traits to others. Some microbes even produce chemicals that destroy antibiotics.

Paradoxically, the very popularity of antibiotics has led to their growing ineffectiveness.

People around the globe ingest millions of pounds of antibiotics each year for ailments ranging from acne to potentially lethal infections of the heart and lungs. But much of that consumption, experts say, is indiscriminate and unnecessary.

Patients often demand antibiotics for minor viruses--coughs, colds, sore throats and runny noses--even though such medicines have no effect on viruses. Rather than tell patients to take over-the-counter medicines and wait out their symptoms, many doctors cave in and give them antibiotics. If they don’t, physicians fear, patients will dump them and find someone more malleable.

“It’s almost as if the visit wasn’t worth anything if they didn’t get a prescription out of it,” said Morgenstein, the Glendale physician who also is president of the Infectious Disease Assn. of California.

Authorities say that even in cases where antibiotics are properly prescribed, patients often confound matters by taking some but not all of their pills, stopping as soon as they feel better. The result: Some of their bacteria survive, building resistance.

In addition to human consumption, antibiotics are widely used to treat cattle, pigs, poultry, commercially raised fish and even trees and honeybees. Farmers use the drugs to fatten livestock as well as to cure disease.

Bacteria in animals have developed resistance as well, and those microbes can spread to humans. In 1985, two people died and several hundred others were sickened in California after eating hamburger meat contaminated with drug-resistant salmonella. The germs were traced to a farm where cows were treated with penicillin and tetracycline at doses too low to kill the bacteria.

Humans often acquire drug-resistant microorganisms in schools, day-care centers, prisons, nursing homes and shelters for the homeless. But the worst spawning grounds are hospitals, where patients with surgical wounds or weak immune systems are susceptible. Bacteria often are spread by doctors, nurses and service workers who do not follow infection control rules such as frequent hand-washing.

“One of the most serious problems is doctors who somehow think their hands are not going to transmit bacteria,” said Dr. David Dassey, an epidemiologist with the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services.

*

The consequences of an outbreak of drug-resistant bacteria can be devastating. Eighty patients in one Japanese hospital died in 1990 and 1991 during an eruption of drug-resistant staphylococcus aureus, a particularly virulent germ that causes blood and skin infections. Beginning in the late 1970s, an epidemic of resistant staph aureus in Australian hospitals killed 75 patients.

Drug resistance exacts a heavy price in dollars as well as death and illness.

Resistant microbes require longer treatment with newer, more expensive drugs, and the cost of treating those infected with such germs has been estimated as high as $30 billion a year in the United States alone. Treating a single case of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis can cost $150,000--10 times as much as ordinary TB.

While antibiotic resistance is increasing in a variety of bacteria, the problem is perhaps most dramatically illustrated by the growing incidence of resistant tuberculosis.

Once the leading cause of death in the United States, TB was all but eliminated by antibiotics. But the disease has made an alarming comeback in recent years. In 1992, the number of cases rose to 26,673--a 20% jump over the 1985 number.

Experts say about 3% of new cases are drug resistant, although the rate is far higher in some places. In New York City, 33% of the new cases reported in April, 1991, were resistant to at least one drug; 19% were resistant to the two most common anti-TB medications.

Drug-resistant TB outbreaks have struck hospitals, homeless shelters and prisons. Beginning in 1990, more than 230 people were infected with resistant TB at hospitals in New York, New Jersey and Florida, as well as the New York state prison system. At several hospitals, many patients did not respond to as many as seven drugs.

In most cases, those who acquired resistant TB were infected with the AIDS virus. Their condition deteriorated rapidly after they contracted resistant TB, with most dying within four months of diagnosis.

In Los Angeles, resistant TB is not a major problem, according to Dr. Paul Davidson, head of Los Angeles County’s TB control program. Only 1.5% of the 1,800 new TB cases in the county last year were drug-resistant strains, he said.

Antibiotics also are increasingly ineffective against streptococcus pneumoniae, the most common bacterial cause of pneumonia. Drug-resistant pneumococcal strains in the United States each year account for at least 50,000 cases of pneumonia, as well as 3,000 cases of blood infections and 600 cases of meningitis.

A less serious but far more widespread problem is a middle-ear infection called otitis media that usually affects children.

According to the National Center for Health Statistics, such infections sent Americans to a doctor 24.5 million times in 1990--a 145% increase over 1975’s total. Several bacteria cause otitis media, and they are gaining drug resistance.

Inner-ear problems often lead to fluid buildup that requires insertion of a small drainage tube through the eardrum. About 1 million children a year undergo such operations, said Dr. Ben Schwartz, chief of childhood and preventable diseases at the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

The more potent drugs needed to overcome resistant bacteria frequently have more adverse side effects.

To combat resistant pneumococcal infections, doctors often turn to a newer class of drugs called cephalosporins. But those drugs can cause liver problems, anemia and, if given in too high doses, seizures, said Dr. Mitchell L. Cohen, chief of the CDC’s division of bacterial and mycotic diseases.

The most alarming aspect of the resistance problem is the handful of mutant strains that are not susceptible to any antibiotic.

Patients with fully resistant tuberculosis often must have all or part of an infected lung surgically removed, said Dr. Michael Iseman, chief of tuberculosis services at the National Jewish Center for Immunology and Respiratory Medicine in Denver. At his hospital, Iseman said, patients usually survive such operations, but sometimes do not.

Those who cannot tolerate surgery must be quarantined, a throwback to the sanatorium system that prevailed until the advent of penicillin in the 1940s. Indeed, Florida and Texas are reopening long-shuttered sanatoriums for extended care of people with highly or completely resistant TB, he said.

Although the number of deaths from drug resistance is relatively low, experts say the toll could rise steeply if highly infectious staph aureus acquires resistance to the still-powerful antibiotic vancomycin.

Common in hospitals and easily spread, staph aureus enters the bloodstream through breaks in the skin, causing high fevers, shock and death. Some staph mutants can be stopped only by vancomycin, but many researchers say it is just a matter of time before the bacteria picks up resistance to vancomycin from strains of enterococcus that can already stave off the drug.

California public health officials issued dire warnings in August after an outbreak of vancomycin-resistant enteroccocus rippled through a small private hospital in Los Angeles County--the first such incident in the western United States.

Nine elderly women and a man were infected, forcing hospital and public health officials to isolate them for weeks. (Authorities declined to name the hospital, saying publicity could hurt it financially and persuade other medical facilities not to report similar problems.)

If staph aureus acquires vancomycin resistance, experts say, the result will be a public health calamity. With its ability to easily infect surgical wounds as minor as stitches, vancomycin-resistant staph aureus could kill healthy people who entered hospitals for elective surgery.

“If you can’t treat (staph aureus-infected patients) with vancomycin, they’ll die,” said Dr. Jon Rosenberg of the state health department’s communicable disease division. “You’d have hundreds or thousands of cases statewide.”

Since infectious bacterial diseases were widely viewed as eradicated by the late 1960s, development of new antibiotics has slowed considerably. A spokesman for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America said only two or three antibiotics for drug-resistant microbes are under development, and are not expected to reach the market for at least five years.

But researchers are taking novel approaches to the problem. They are looking at ways to replace antibiotics with vaccines, and a vaccine against drug-resistant pneumonia is in use. Scientists also have found substances that can inhibit bacterial enzymes that break down antibiotics.

Many meat and poultry producers are using fewer antibiotics as growth agents, and hospitals have become more aware of the importance of vigorously enforcing infection control procedures. Experts applaud both trends as ways to reduce resistant bacteria in the environment.

Authorities warn, however, that doctors must stop prescribing antibiotics so much and the public must stop demanding them for ailments they are not designed to treat. As antibiotics are used less, the resistance problem should not worsen.

But will humans ever regain the upper hand over bacteria that antibiotics once provided?

“You don’t know what’s going to happen,” said Dr. Ellie Goldstein, a UCLA infectious disease specialist. “There are constant skirmishes. Who’s going to win is yet to be determined.”