Vaught Is Sole Survivor : One by One, Best Clippers Left Him Behind

- Share via

Charles Smith went first . . . .

He was not only Loy Vaught’s best friend on the Clippers, he was the first of their talented young players to engineer his own departure. Within two years, Smith was followed by Ken Norman, Danny Manning, Mark Jackson and Ron Harper, and Vaught became the leading scorer and rebounder for a team starting over.

Like the Mark Twain character facing hanging who said he’d as soon miss it if wasn’t for the honor of the thing, Vaught isn’t sure what to think.

“It’s real tough,” he says. “Losing does take a toll on you.

“I’d be telling stories if I’d played like everything was nice. It’s nice to put up good individual stats and everything, but it’s better to win.”

Five seasons and he’s second only to Gary Grant among the Clippers in time of service. It took a tough young man to watch everyone else escape, without starting his own tunnel, but Vaught did.

“I hear that a lot from Danny Manning,” he says. “He always kids me about how I’m still here, stuff like that. It’s hard, you know, but I’ve put in this much time.

“Next year will be my sixth year here, so I’ve come this far, I might as well see it through. They’ve been fair to me. You hear a lot of gripes about how other guys were treated unfairly by management. I haven’t had any problems.”

Actually, he’s had a few.

Start with the makeup of the team when he arrived in the fall of 1990, with Manning, Smith and Norman all ahead of him. A player who thrived on work, Vaught averaged 16 minutes as a rookie.

Then came the next season--and next coach.

Mike Schuler was succeeded by Larry Brown, devotee of a motion offense, which placed a premium on players with ball-handling skills. Vaught was a no-frills jump shooter/rebounder, and his name started popping up in trade rumors.

Next up, in Vaught’s fourth season, was Bobby Weiss, last of the players’ coaches. By then, the atmosphere was so poisonous in the dressing room, you needed a gas mask to dress before games. . . .

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

*

Charles Smith went first. . . .

Drafted the year after Manning, he blossomed while Danny was recovering from knee surgery.

A rivalry blossomed too. Charles wanted Manning-type money. During negotiations, which tended to drag among the Clippers, Smith injured his own knee, and management backed off.

In July 1992, Smith surprised everyone, signing the one-year qualifying offer the club was obliged to make after his first contract was up, taking a 25% raise--far less than the Clippers would have given him on a long-term deal--but forcing their hand. In a year, he’d be an unrestricted free agent.

Faced with losing him, they traded him for Stanley Roberts and Mark Jackson.

“Charles was my best friend,” Vaught says. “Even though he played ahead of me. . . . He was my best friend on the team. I had mixed feelings.”

Norman went next. . . .

He wanted $12 million over four years. The Clippers offered $10 million. They might have figured out there was a problem a year or two before when Snake was still tradable, but they didn’t. He left in the summer of 1993.

Manning went next. . . .

He had been promising he would leave from Day One. When negotiations for his rookie contract stalled, Manning’s hard-nosed agent, Ron Grinker, called Clipper owner Donald Sterling a “stooge.” Manning held out until NBA Commissioner David Stern, in Los Angeles for a party, asked Sterling to let him step in, put then-Deputy Commissioner Gary Bettman on the phone with Grinker and made the deal.

Grinker said Manning would finish his contract and sign his one-year qualifying offer. When the Clipper office opened July 1, 1993, Grinker and Manning showed up and did just that. By the following February, Sterling finally had reconciled himself to losing his franchise player, and Manning was traded for Dominique Wilkins.

Wilkins, Jackson and Harper went in a group. . . .

The Clippers had decided that Wilkins’ $21-million asking price was about $11 million too high. Harper had spent the season complaining he was in “jail,” while drawing a $4-million salary. Jackson, plump and depressed, just wanted out.

“They let it be known they were going to go,” Vaught says. “A lot of it did make it into the papers, but in the locker-room situation, they really let everybody know how they wanted out. So I knew that they wouldn’t be returning.

“Last year was tough because of all the internal problems. It got tough to come to practice. You know there was no camaraderie at all, no friendship at all. Guys were sour. It was just a hard situation. . . .

“I call them the dog days because people would just come here, would not want to be here, hating to have to come to practice, killing the coach. I’m not going to name names, but it was just tough.”

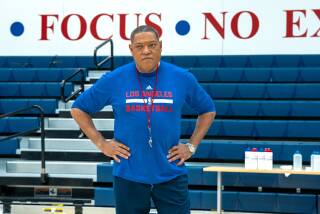

With few recognizable players, the Clippers hired Bill Fitch to start pushing the boulder back up the hill.

A no-nonsense coach who would turn in his whistle before he ever paid a player a compliment he hadn’t earned, Fitch took a season-long look at Vaught . . . and was pleased.

“I knew that Loy was, statwise, a good rebounder,” Fitch says, “but he didn’t play a real consistent game, scoringwise. I looked at the rebounding go along, (then) fall off. And I heard all the stories about how he was soft. So that’s what I was (expecting), a guy that was high and low and soft.

“But he worked. Every day in camp, he worked like a rookie instead of a veteran. Took criticism good on the areas I felt would make him better.

“If he’s ever going to be a super-super, it isn’t because God made him a super-super. It’s going to be because God gave him the ability to work hard enough to be a super-super.”

Vaught fears humiliation, which he believes can attach itself to a player’s career, and this season’s 0-16 start was too close for comfort.

The crawl down the stretch hasn’t been any consolation.

“It’s a better feeling still,” Vaught says. “You don’t have guys concerned with distracting things like how much money they’re going to get on their next deal, where they’re going to be next season, getting out of here. You have guys who are more concerned with just trying to win and trying to get better.

“I have hope. I think Coach Fitch is a good coach, a great coach. I think that if you give him a superstar coming out of the draft or if he can acquire a superstar by way of a trade, I think he can win. . . . He’s had Stanley Roberts hurt, we’ve played with no center, and he’s found a way to almost get up to 20 wins. He’s got us working hard and that’s a compliment to him.”

Given what they’ve been through, it’s a compliment to them all.

Vaught, nicest of the nice guys, finishes his interview. The reporter puts away his tape recorder.

“Now you can tell him what you really think,” says a teammate, laughing.

Oh, no, it was even worse than that? Assuming they get beyond it, that will only make everything sweeter.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.