Major Step in Gene Therapy Reported : Medicine: Three children are thriving two years after treatment. Permanent insertion of the material is breakthrough.

- Share via

The first newborns to undergo gene therapy are healthy and the inserted genes are working normally nearly two years after the procedure, researchers from Childrens Hospital in Los Angeles will announce today.

Dr. Donald B. Kohn of Childrens, head of the team that performed the therapy, is scheduled to declare the effort a qualified success at a meeting of the American Pediatric Society in San Diego.

The results are encouraging for more than just the three children who underwent the procedure in Los Angeles and San Francisco. This is the first time that researchers have been able to insert genes into the blood cells of humans permanently, said Dr. W. French Anderson of USC. In all previous cases, the insertions have been only temporary, which means the procedures had to be repeated at regular intervals.

Kohn said this advance represents “a major step toward gene therapy” for the treatment of a broad variety of genetic diseases. And, he concluded, “If we can correct genetic defects at birth, we can prevent the severe problems that follow.”

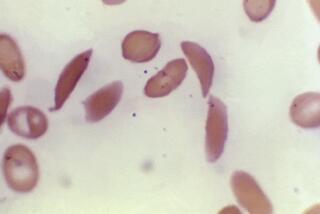

The three infants were born lacking an enzyme called adenosine deaminase, or ADA, whose absence prevents immune systems from fighting off viral and bacterial infections. That absence produces a rare, normally fatal disorder called severe combined immunodeficiency disease, or SCID--the disorder suffered by David, the well-known Houston “bubble boy,” who died from it in 1984 at age 12. Since David’s death, researchers have developed a drug called PEG-ADA to treat the enzyme deficiency, but it costs $250,000 a year.

Kohn and his colleagues isolated white blood cells from the infants’ umbilical cords at birth, altered the cells so that they began to produce ADA, and reinfused the cells into the infants four days later.

In an interview, Kohn said the Childrens team is “very encouraged” by the results to date. “There are no problems from it (the gene therapy), and we are confident that we might have a permanent benefit from it. . . . Based on these results, we would definitely apply it to other kids.”

Only about 25 children with ADA deficiency are born in the United States each year. But the technique pioneered by Kohn could have much wider application. It could be used to treat many of the thousands of children born each year with one of the 3,000 congenital disorders caused by defective genes.

Tuesday afternoon, Andrew Gobea, the first infant to receive the therapy, was playing at his home in the Imperial Valley and preparing for his second birthday tomorrow. “He goes everywhere and does anything that a normal 2-year-old does,” said his mother, Crystal Emery. “We’re very pleased with the results so far.”

Andrew, who underwent the procedure in Los Angeles, is still receiving weekly shots of PEG-ADA that were begun at birth to ensure his health while the team studied his white cells to determine whether the engineered cells were surviving. When they were confident that the cells had survived, Kohn began tapering off the shots and hopes eventually to eliminate them altogether, much to Emery’s relief. Andrew “runs away from the shots. He doesn’t like them at all,” she said.

The other two children, who underwent the procedure in San Francisco, are healthy and live out of state, the scientists said.

The gene therapy procedure itself is theoretically quite simple. Researchers insert a copy of the healthy ADA gene into a common virus, called a retrovirus, that invades dividing cells and inserts its genes into the cells’ own genetic material. They draw blood from the patient, expose the white blood cells to the virus so that the healthy gene is inserted into the cells, and then put the cells back into the blood-stream.

This is the procedure that Anderson and his colleagues at the National Institutes of Health had previously used on two older girls, Cynthia Cutshall, now 14, and Ashanthi DeSilva, now 9. The technique restored their immunity, and the pair have now been healthy for five years. But because white blood cells are cleared slowly from the bloodstream, the girls have had to have the procedure repeated every six months to two years to provide a fresh batch of engineered cells.

In an effort to make the “cure” permanent, researchers have attempted to engineer stem cells, the relatively small number of white blood cells that reside in the bone marrow and serve as the progenitors, or parents, of all blood cells.

But human stem cells divide very slowly, and it has proved extremely difficult to get the retroviruses to infect them and insert the healthy gene. In fact, Anderson said Tuesday, attempts to engineer Cynthia’s and Ashanthi’s stem cells have failed.

Many of the stem cells in newborn infants, however, are still dividing and are readily attacked by retroviruses. Instead of collecting these cells from the infants, Kohn chose the less invasive procedure of isolating them from the blood left behind in the umbilical cord at birth. It was these cells that were engineered and reinfused into the children.

Kohn’s team collects blood samples from the children each month and analyzes them for the presence of white blood cells containing the ADA gene. He will tell the San Diego meeting that cells containing the healthy ADA gene have remained in the blood since birth and that the number of such cells has been growing in recent months as physicians have tapered off the ADA replacement drug.

Kohn concedes that the technique is not perfected. In particular, researchers need to put the healthy gene into a much larger percentage of the patient’s stem cells than is now possible. In Andrew’s case, the gene found its way into only 0.01% of his stem cells.

But that small percentage is producing a much larger percentage (5% to 7%) of crucial immune cells in the blood that contain the healthy gene, and they hope that percentage will continue to grow. That is very promising, Kohn concluded, because some studies have shown that only 10% of the normal amount of ADA is sufficient to prevent symptoms of SCID.