The Superstore Phenomenon

- Share via

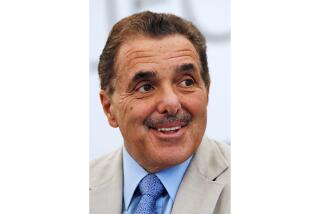

In 1992, when the Borders bookstore chain operated just 19 “superstores,” it planned to take the business public. The offering was much anticipated in the publishing world--Borders CEO Robert DiRomualdo had already been called a bookselling “visionary”--but the stock sale never came to pass. The Kmart Corp., owner of Waldenbooks, swept in with an offer of its own, and the Ann Arbor-based Borders, to the dismay of many would-be investors, soon became a jewel in the Kmart crown.

Those disappointed stockholders now have a second chance, however, for Borders is scheduled to go public again in the next few months. It’s not the same Borders--the company is now the Borders Group, having absorbed Kmart’s 1,100 or so Waldenbooks stores, and its superstores now bear the name Borders Books & Music--but book people are again enthusiastic, for the three years that have elapsed have only burnished Borders’ image as the bookstore chain against which others are measured.

With 85 superstores and about $700 million in annual sales, Borders trails far behind New York-based Barnes & Noble (269 superstores with $953 million in annual sales), but the rapidly expanding Michigan company seems to have the competitive edge for the moment. Unlike its major competitors, Borders hasn’t cannibalized past successes. Crown books and B&N; currently are in moderate retrenchment, closing scores of smaller, mall-based stores made obsolete by the superstores’ prosperity; Waldenbooks is doing the same but hopes to profit from the experience of its new parent.

A solitary shop as recently as 1985, Borders plans to be operating 110 superstores--a category that didn’t even exist half a dozen years ago--by the end of this year. By June it will have five outlets in the Los Angeles area, in Mission Viejo, Torrance, West Hollywood, Santa Monica and Westwood.

Stressing service over pricing, comfort over convenience and depth of selection over stacks of bestsellers, Borders has created a chain that seems as attuned to the new world of technology as the refined old world of literary society. The story of its growth belies, for now, the notion of computer enthusiasts that the era of the printed text is coming to an end.

In the early 1980s it looked as though the chain bookstores, then epitomized by Waldenbooks, B. Dalton and Crown Books, were going to roll over independent bookstores across the country--and perhaps change the shape of U.S. culture--by pushing heavily the sale of best-selling titles at discount prices. And to some extent that happened; many independents went under, and sales of heavily marketed books went through the roof. Strong and well-stocked independent stores thrived, however, and one of them was Borders, located in Ann Arbor half a block from the University of Michigan. Founded by brothers Tom and Louis Borders in 1971 as a used bookstore, it was conceived as a kind of community center--a commercial enterprise, to be sure, but not one slavishly devoted to the bottom line.

For years the Borders brothers, who rarely talk to the press, concentrated on their single store, with Tom Borders, a former English professor, doing the up-front merchandising and Louis Borders, a mathematician by training, the back-room buying. They had dreams of going national, however, and even a secret weapon: a proprietary inventory control system devised by Louis Borders in the mid-70s. The IBM-mainframe system streamlined the ordering and restocking process, and allowed Borders to determine instantaneously which titles and subjects and authors were hot, which were seasonal, and so on.

The Borders brothers initially hoped to grow the business by forming Book Inventory Systems Inc. (BIS), a company that would install their inventory control system in other bookstores. There were few takers, however, for the system was geared to large, high-volume stores. In order to expand, the Borders brothers realized, they had to build their own stores. As late as 1990, when there were five Borders stores and half a dozen BIS-serviced stores, the brothers’ plans didn’t seem particularly ambitious: Bob DiRomualdo, by then CEO of Borders, told a business magazine that year, “We’re not interested in building dozens and dozens of bookstores. . . . Let the chains have the numbers.” That’s no longer the case, of course, and it’s hard to miss the irony--that the limited success of BIS, and the outright failure of Borders’ franchise plans, fueled the birth of book superstores that would help put many independents out of business.

DiRomualdo, hired by Borders in 1988, knew of the company from a BIS-client store in Toledo, where he had run food retailer Hickory Farms. It was only after seeing Borders’ crowded, lively store in Indianapolis, however, that he became convinced of the chain’s potential. “If they could have this kind of following here,” he recalls telling himself, “you could have 500 of them.” DiRomualdo was also impressed by Louis Borders’ inventory system, which by then had incorporated artificial intelligence. Bugs in the program limited Borders growth in the early 1990s, DiRomualdo says, but now delivers as it should, keeping salespeople out front helping customers rather than in back rooms doing paperwork. Today Borders’ inventory-control system is considered, according to Jim Milliot, business editor of the trade magazine Publishers Weekly, “the industry standard.”

The current system, says Borders vice-president for marketing Dan Conetta, “mimics the thinking of a very good professional book buyer”--if the buyer knows, that is, the title, quantity and sales rate of the 125,000 titles found in the typical Borders store. The result, he says, is that “If someone shops a Borders constantly, the store begins to resemble the customer”--begins to reflect, in other words, the customer’s tastes and tendencies. DiRomualdo puts it this way: “Stores in Miami and Anchorage will have radically different inventory, especially over time.” Store management is likewise decentralized, though Borders does maintain central managerial philosophies, such as the belief that employees (“associates”) should be well-educated; prospects must pass a test--in literature, music or computer topics--for the department in which they hope to work. “A huge assortment requires good people,” says DiRomualdo. “When you’ve got a reputation for a great selection, people are going to ask you tough questions.”

No, the book isn’t dead, or even dying--as DiRomualdo points out, one of Borders’ best-selling categories is computer books. Nonetheless, Borders is better prepared than most bookstores to ride out a decline in the sale of printed texts: Every new store carries many thousands of music, video and multimedia titles (the Westwood store is the first to have a full-fledged, 2,000-title multimedia section). If there’s a book superstore shakeout on the horizon, as some industry observers predict, Borders isn’t likely to be a casualty.

Borders’ sales were up 85% overall in 1994, to $200 million, which tells you that print mavens appreciate the chain’s approach to bookselling. (Barnes & Noble’s 1994 sales gains were likewise healthy--up 21%, to more than $1.62 billion.)

For competitors, though, Borders’ arrival in town is often a nightmare. The inventory control system allows Borders to keep its costs down, holding its return rate (booksellers are permitted, for a few months after publisher shipment, to return unsold books for credit) to about half the industry average, or under 10%; its policy of differentiating one store from another keeps Borders stores from seeming antiseptic, homogenized and out-of-place.

When competition from the Borders/B&N; superstore juggernaut forced Chicago’s venerable, home-grown bookstore chain, Kroch’s & Brentano’s, to close half its 20 outlets in 1993, one of its book-buyers complained that the superstores had “stolen or borrowed the whole concept of the independent bookstore.” She was right, too--if you overlook the facts that K&B; is itself a chain, that Borders also began life as an independent, and that its chain incarnation is an attempt to recreate that store’s success on a mass scale. As Avin Mark Domnitz, president of the American Booksellers Assn., said last year, the chain superstores have simply been “mimicking the small independent bookstores, only doing it bigger and better.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.