The Angriest Actor : Native American activist Russell Means focused his fierce will at Wounded Knee. Can a revolutionary co-exist with ‘Pocahontas’?

- Share via

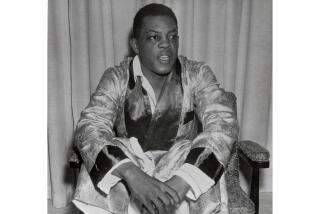

CHINLE, Ariz. — Russell Means has collected a number of heavy-duty credits--though not the sort usually associated with show business folk.

While his acting colleagues were boning up on “The Method” and Stanislavsky, he and fellow American Indian Movement leader Dennis Banks led a 71-day armed siege at South Dakota’s Wounded Knee Reservation. While other actors waited on tables, he was incarcerated for a year for obstructing justice in a 1974 Sioux Falls riot.

While they worked on movement and muscle tone, he publicized his people’s desire for self-determination by forming controversial alliances with Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt, the Nation of Islam’s Louis Farrakhan, the Rev. Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church and the Libertarian Party, whose 1988 Presidential nomination he sought.

Yet the leap from political activism to acting, colleagues say, is smaller than one might think -- a natural extension of a 25-year battle waged by one of America’s savviest showmen.

“Russell has always been very mediagenic,” says Hanay Geiogamah, who joined AIM in 1971 and now co-produces a series of Native American TV movies on TNT. “He was eloquent, capable of synthesizing complex political ideas for the press and, with his long black braids and statuesque physique, the image the media wanted to see. Russell was smart enough to realize that when you’ve got it, you’ve got it. He used the system . . . and used it well.”

If Means--who made his motion picture debut as the title character in 1992’s “The Last of the Mohicans”--is using the motion picture industry, it’s without question a two-way street.

When he surfaces as the voice of Pocahontas’ father, Chief Powhatan, in the Disney animated feature opening Friday, he brings not only dramatic skills but instant legitimacy and authenticity. It was an inspired move by a studio that stumbled into a minefield with its portrayal of Arabs in “Aladdin” in 1993.

“I haven’t abandoned the movement for Hollywood. . . . I’ve just added Hollywood to the movement,” says Means, whose speech and gait reflect his abhorrence of hurrying.

Abalone earrings with an eagle imprint set off his penetrating brown eyes. Waist-length braids are bound in silver-trimmed burgundy suede. “The entertainment world is a powerful venue for revolution, particularly now that there are 500 channels on the horizon and the global market is so big. The Great Mystery has, once again, put me in the right place at the right time.”

*

Reared on John Wayne and Randolph Scott movies glorifying the slaughter of his people, Means was put on the defensive early on. Almost as unhappy with what he considered the stereotypical portrayals in more recent offerings such as “Black Robe,” “Geronimo” and even “Dances With Wolves” (whose “white savior” story line led him to dub it “Lawrence of the Plains”), he vowed to work from within.

In a multimedia assault on Hollywood, the 55-year-old Oglala Lakota Sioux wrote a treatment for a detective series in which he’d star with his son, is developing a cartoon show based on Native American legends and recently portrayed Sitting Bull on CBS’ “Buffalo Girls.” On the big screen, he is co-producing a drama about Wounded Knee with Warner Bros. and has turned out a screenplay about Central American Indians. Portraying the ghost of Jim Thorpe in the Disney Channel’s “Wind Runner,” he also was featured in the John Candy comedy “Wagons East” and played a dangerous shaman in “Natural Born Killers.”

“Russell’s a renegade with one foot in both corrals, someone who has walked a crooked and strange life,” says director Oliver Stone. “He’s a very authoritative presence with his own brand of magic. Whether he’s acting or not is hard to say.”

Recalling the freewheeling “genius” of Robin Williams as the voice of “Aladdin’s” genie, imagining the basso profundo voice-over pros he’d be up against, Means headed for the “Pocahontas” audition with considerable trepidation. Disney, too, didn’t know what to expect.

“No one doubted that Russell is an imposing personality,” says Jim Pentecost, producer of the movie. “The question was whether he could come across on voice alone. The fact that he’s such a figurehead was a double-edged sword. Like any activist, he might object to what we were doing.”

Initially, Means admits, he had some problems with the script. Native Americans addressed each other using proper names rather than the traditional “my father” or “my friend,” and at one point a Pueblo melody was inserted in place of music of the Powhatans--the tribe indigenous to colonial Jamestown where, according to legend, the Indian princess (portrayed by Irene Bedard) prevented the execution of Capt. John Smith (Mel Gibson) and managed to avert a war.

Still, Means says, “scholastic, linear-thinking nit-pickers” fixated on the movie’s historical inaccuracies are missing the point.

“ ‘Pocahontas’ is the first time Eurocentric male society has admitted its historical deceit,” says Means. “It makes the stunning admission that the British came over here to kill Indians and rape and pillage the land.

“ ‘Lion King’ was this generation’s ‘Bambi,’ demonstrating that animals have feelings and causing children to question the morality of sport hunting,” he continues. “ ‘Pocahontas’ teaches that pigmentation and bone structure have no place in human relations. It’s the finest feature film on American Indians Hollywood has turned out.”

The activist-cum-actor is sitting in the living room of a modest, prefabricated two-bedroom house in this community of 5,000--site of the Navajo Reservation’s breathtaking Canyon de Chelly and a world away from Spago. His Federal Express address is “half-a-mile northwest of Church’s Fried Chicken.” A hand-printed sign--”Please remove thy shoes”--is posted by the door.

Books such as Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War” and “Strategic Investing” sit on the shelves. Navajo rugs line the floor. A black cat and a deaf Dalmatian roam the 13-acre property, eyeing the five horses in the corral. A fax machine and a 31-inch TV keep Means plugged into the fast track.

Means and his fourth wife, Gloria, had the house built in 1987--opting, in the Native American fashion, to live in a new home rather than inherit the spirits of past occupants. Though the two are divorced, Means heads to Chinle twice a month to see their sons, ages 10 and 4. He divides the rest of his time between Porcupine, S.D., and a rent-controlled Santa Monica apartment where a friend’s daughter’s bicycle--or running--is his transportation of choice.

If family is a mainstay of Native American life, it’s a new-found priority for Means--father of 13 (about half of them adopted) and grandfather of 18.

“Yasser Arafat was right when he said that revolutionaries shouldn’t be married,” he says. “It’s sad, but work has always come between me and my relationships. Though they all turned out well, it breaks my heart that my children were without me at important times of their lives.”

What turned things around was a 30-day total-immersion treatment program at Arizona’s Cottonwood de Tucson (“a non-Indian hideaway for rich people”) in which Means enrolled after “The Last of the Mohicans” wrapped. The therapy not only enabled him to work through unresolved issues with three younger brothers and an abusive, if loving, mother, but probably saved his life, he says. Without AIM as an outlet--and, before that, alcohol and drugs--anger was making him “self-destructive and suicidal.”

“Like Nixon, I had a hit list, targeting Indians and non-Indians alike,” says Means, who can reel off titles and dates of treaties the United States has broken with his people. “Rather than becoming a martyr, I discovered that my anger was rooted in low self-esteem. That surprised everyone I knew--including me.”

Means encountered racism early on when his father, a welder and auto mechanic, moved the family from South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation to Vallejo, Calif., dropping him into an unfamiliar, racially mixed world.

At 16, he enrolled in a virtually all-white school in San Leandro where he faced a barrage of ethnic insults and drifted into delinquency. After his high school graduation, he worked as a ballroom dance instructor, a cowboy, a day laborer and an accountant. Though he attended five colleges, officials refused to transfer credits, he says, preventing him from earning a degree.

The establishment of AIM in 1968 gave Means a much-needed sense of direction. Excited by its militancy, he founded the group’s second chapter, in Cleveland. In an event he calls “the most photographed of the 1970s after Watergate and Vietnam,” he co-led a 1973 takeover at Wounded Knee. It was the first time, says Means--a staunch advocate of Native American separatism--that he ever felt “free.” Though the standoff left two Native Americans dead and a federal marshal paralyzed, the felony charges against Means and Banks were ultimately thrown out on grounds of prosecutorial misconduct.

If some view his foray into show business as a cop-out, others say Means is playing the game on his own terms. Refusing to be part of the “meat market,” he adopts a deliberate monotone at auditions. He has passed up scripts containing negative stereotypes. He won’t work for Ted Turner because the Atlanta Braves owner championed the “tomahawk chop”--an “obscene gesture toward American Indians”--on nationwide TV. Acting lessons have never been part of his game plan.

Means agreed to read for the title role in “Mohicans” provided the producers sent a first-class ticket by mail. (Arriving at the airport to find a coach seat reserved, he turned around and went home.) Unexpectedly asked to stay overnight once he arrived in L.A., Means later handed an astounded producer a $600-plus Neiman Marcus bill to cover the cost of “basics.”

On the “Mohicans” set, Means formed a close bond with co-stars Daniel Day-Lewis and Eric Schweig and the three threw their support behind Native American extras protesting low pay and poor housing--an outgrowth, according to director Michael Mann, of the shortage of motel rooms in that part of North Carolina. Means served as their liaison to the filmmakers. He also forwarded his running list of alleged racist activities and remarks to the Directors Guild.

“Russell has mellowed some from his eye-for-an-eye days,” says Bonnie Paradise, a Shoshone Paiute and executive director of the now-defunct American Indian Registry, which cast “Mohicans.” “But he hasn’t let go.”

Whatever might have passed in conversation between individuals, counters Mann, the production was an eminently equitable one. “I don’t tolerate racism on a set of any picture I direct,” he says. “Whenever I hear about it, I come down heavier and faster than anybody.”

Though Means was happy with “Mohicans”--a picture he considered a vast improvement over past portrayals of Native Americans--he was upset with a “stereotypical” scene in which a British officer’s daughters were captured and brought back to Native American warriors. He also had problems with Mann’s insistence that he wear a loincloth he considered too small.

“Michael has his vision and you have to place complete confidence in him,” Means says. “In contrast, Oliver Stone is very inclusive of artists. Since he’s not loud or demanding, it’s hard to tell who’s in control. You wonder if he can put it together because everything seems to be chaotic . . . but he does.”

Given a chance, Stone says, Means has the potential for a broad-based career.

“Russell will always be an Indian, but he can play non-traditional roles--storekeepers, husbands,” he maintains. “With that great stone face to bounce off of, there’s no reason why he can’t even do comedy.”

Means calls Stone an “anarchist like myself.” To anyone following Means in the 1980s, however, his leftist stance was very much in doubt. Though his political transformation was nowhere near as extreme as Jerry Rubin going Wall Street or Eldridge Cleaver taking up fashion design, it was still the topic of much debate.

Fern Mathias, director of the Southern California chapter of the national AIM, has little patience for a man who ran for vice president on Larry Flynt’s presidential ticket and sought the Libertarian presidential nomination in 1988.

“Russell is a charismatic leader,” acknowledges Mathias. “But he’s out to push Russell Means--not to take care of the Indian people. A few months ago, he spoke in San Diego wearing purple pants, a purple silk shirt and red lizard boots. He’s always wanted to be a star.”

Hanay Geiogamah disagrees. “I think that, given all the attention he received, Russell has kept his head on pretty straight,” he maintains. “As for his ‘party-shopping,’ he has always been pragmatic. He was keeping Indian issues fluttering out there when few others could.”

M eans has long been a light ning rod for controversy. His aggressive tactics were condemned by some members of a Native American population he describes as “traditionally non-confrontational.” And his propensity for the spotlight rubbed some the wrong way.

Means makes no apologies. Not for his grandstanding--”At AIM we were expert at community theater; the squeaky wheel gets the oil”--nor for his career trajectory. Far from abandoning his roots, he says, he’s established the Treaty Fund on the Pine Ridge Reservation. The organization is creating a total-immersion school in which all subjects are taught in Lakota, developing a psychological treatment center along the lines of Cottonwood, running the nation’s only Indian-owned-and-operated radio station as well as an ambulance service and operating a Native American Anti-Defamation League.

His move to the right, Means says, had philosophical and practical underpinnings. His only regret, he says with a twinkle in his eye: trusting the white man one more time.

“The Libertarians told me to charge the campaign to my credit cards and they’d reimburse me,” recalls Means, who embraced the party as an alternative to “America’s one-party system--the ‘Demopublicans.’ ” “Five years later, I was still paying it off.” (A spokesman for the Libertarians concedes that while certain officials may have made the commitment, the party’s policy is to provide financial support only to the “bonafide candidate, rather than to people seeking the nomination.”)

Putting together his second CD--a mix of jazz, blues, rock, and rap--brought Hollywood’s Democratic leanings into sharp focus. Whereas his first CD featured Native American rap music (“Rapajo”), Means targeted his current sociopolitical message at a broader audience. The record companies loved “Nixon’s Dead Ass,” a cut about revisionist history, he says; but he claims that “Waco”--a song critical of President Clinton and Atty. Gen. Janet Reno--met with such resistance that he was forced to produce the record himself.

N ext on the agenda is Means’ autobiography, which St. Martin’s Press is publishing in September. Means worked with co-writer Marvin J. Wolf, who mortgaged his house to continue on the project. And, if one believes in karma, the volume was edited by Murray Fisher, who also edited “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” and “Roots.”

“I was sitting in a deli with a Paramount producer, my co-author and editor, talking about turning my life into a movie,” Means recalls, sipping a cup of coffee at the Chinle Holiday Inn. “They were using words like ‘Gandhian’ and ‘epic.’ I thought about the days I was on Skid Row in California, sleeping in church basements, on the road with AIM, the nine assassination attempts on my life.”

A tall, red-headed man comes over to the table and introduces himself as a retired chemistry teacher.

“Excuse me,” the fellow says haltingly, holding out a white cap. “But could I have your autograph? I never do this but certain people are idols of mine because of the stands they have taken. The last person I did this to was Jesse Owens.”

Means pulls out a pen to oblige. “I prefer giving autographs on behalf of the work I’ve done than because I’m part of the shallow world of celebrity and movies,” he says, as the man walks away.

“I’ve had a great experience in Hollywood, met the finest people, made wonderful friends. But the difference between the entertainment world and the front lines is that on the front lines you know you’re right.”*

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.