Recognition Comes for Her Work Against Gangs, but She Shuns It : Woman who lost two sons declines White House invitation. She says others deserve credit too.

- Share via

Most people would gladly accept a personal invitation from the President to receive an award in the White House Rose Garden.

Not Rita Figueroa, who has never boarded an airplane. She says it frightens her too much.

She told an East Los Angeles priest that she was honored, but that she wouldn’t fly even with the Pope. When Atty. Gen. Janet Reno called to suggest that she instead take a train or bus, Figueroa politely declined. It’s her humble nature.

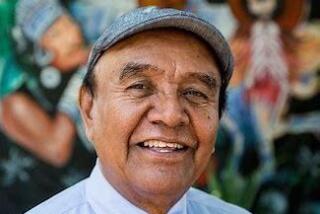

The 65-year-old received the crime victims service award from the Justice Department for her work with an East Los Angeles group called Concerned Parents, which she helped create in the early 1970s after she lost two sons to gang violence. But she prefers not to take all the credit.

“There are a lot of mothers who lost their sons, not only me,” she said. “Without their help, I couldn’t have done anything.”

Of the award’s 10 recipients nationwide, Figueroa was the only one to turn down President Clinton’s invitation. Instead, the award was presented to her June 19 in East Los Angeles at a luncheon with lesser-known local, state and federal officials.

The attention has overwhelmed Figueroa. She is more at ease sharing the limelight, as she did Tuesday, when the Concerned Parents were honored in a get-together and blessing at La Soledad Church on Cesar Chavez Avenue.

Twenty years ago, five mothers began meeting regularly in the church basement to search for ways to protect youngsters from early, senseless deaths. In that sanctuary, many sons’ funerals were also held.

The smell of incense permeated the hot air as Bishop Steven Blair blessed 45 service medals with holy water and presented them to parents affiliated with the group.

Since Concerned Parents’ inception, mothers--and occasionally fathers--from various barrios have worked together to stop inter-neighborhood violence and to serve as a support group for families who have lost children. Parents in the group also have worked alongside parents of rival gang members who have killed their children.

*

When they hear of a killing, Concerned Parents visits the parents to offer comfort. They often collect money door to door to help pay for the funeral.

To prevent fights between youths in warring neighborhoods, the mothers have patrolled the streets and escorted students to school in barrios where they are unwelcome. Some have visited Central Juvenile Hall in East Los Angeles to counsel gang-involved youths.

Friends said Figueroa sleeps little and can still be seen at night walking the streets to protect the local youths.

Figueroa explained that the mothers--many of whom still cry at the mention of their lost children--try not to mention the word gangs or the names of enemy barrios because doing so reinforces localism and hatred. She won’t name which gang killed two of her four sons.

Her first son, Bobbie, was a 17-year-old gang member in 1971 when he was shot in the back. He died after 38 days in a coma. Her second son, Ronnie, was a 16-year-old gang member in 1973 when he was playing football in front of his house. Someone shot him from a passing car, and he died three hours later at the hospital. Her sons’ murderers were sentenced to prison.

*

“Justice was done,” Figueroa said. “But I never wanted revenge. The boys that did it went to court and I left it to God.”

To relieve the pain of her loss, she prays to Our Lady of Soledad (meaning solitude and sorrow)--a statue of the Virgin in a back alcove of La Soledad Church. Figueroa said she can identify with the statue’s painted tears.

“She lost a son too,” she said.

Figueroa said her sons’ deaths prompted her to make connections with other mothers.

“We wanted peace really badly,” Figueroa said. “And we were going to get it by joining together.”

Another member of the group, Maria Montenegro, first accompanied Figueroa to neighboring barrios and introduced her to gang members two decades ago. On a wall in her home, Montenegro has collected about 100 small memorial cards from wakes, each bearing the name of a lost youth. And Montenegro also lights candles for the dead.

“I pray to God we don’t lose more boys,” Montenegro said.

At the end of a typically busy day recently, Figueroa was eager to return home to her husband and 35-year-old son.

“I got to go,” she said. “I’ve got a lot of things to do.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.