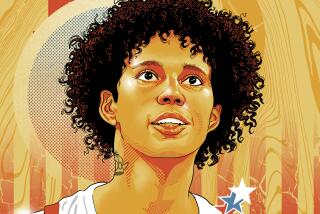

SUNDAY PROFILE : Jenny’s Journey : Marilyn and Paul Skinner of Huntington Beach Have Seen Their Daughter Come a Long Way Since Her Down’s Syndrome Was Diagnosed 24 Years Ago

- Share via

It’s July 5, and in New London, Conn., Paul and Marilyn Skinner of Huntington Beach are among those jammed into Ocean Beach Park to watch the swimming finals in this international meet.

After a year of intensive training and hours of tedious waiting, their 24-year-old daughter, Jenny, mounts the starting platform and begins her ritual of preparation for the 100-meter freestyle.

The starting gun sounds, and Jenny Skinner is off. Network cameras follow her as she pulls herself through the water with the strong, steady stroke that delights her coaches.

It’s the stroke that dominated races back in California, but here at the international meet there is tougher competition. At the finish, Skinner is a close second, earning her a silver medal to go with the one she won in the 100-meter freestyle relay and the bronze medal she won in the 100-meter backstroke. She is gracious in her interview on ESPN, and she echoes her remarks once home.

Seated across the dining room table from her mother, she wants to make it plain that “my mom’s my coach, and she’s really a wonderful coach for me.”

Being in the meet was a great experience, she says. “Actually, it was perfect--not that cold, not that hot, just great. I just loved that place. I hated to leave there. I’d just like to go back.”

On the other hand, she adds, “I’m just glad to be home in my own bed” and back to her routine of Coastline Community College classes, speaking engagements for Athletes Outreach and training for swimming, cross-country skiing and equestrian dressage.

Jenny Skinner--successful athlete, determined student, experienced public speaker--has Down’s syndrome.

*

The Special Olympics World Summer Games--billed as the largest sporting event in the world this year--brought mainstream attention to the accomplishments of athletes with mental retardation. Many of the competitors, like Jenny, have Down’s syndrome.

The condition--which used to be inaccurately called Mongolism because it causes a slight upturn of the outer corners of the eyes--is caused by a defect in the 21st chromosome. Though this was discovered in the 1960s, one of the first genetic disorders identified, how this defect causes its damage is still unknown.

Down’s syndrome affects learning and reasoning ability, auditory and visual memory, muscle tone and language skills. Sometimes the affliction is profound, sometimes much less so.

It remains a common birth defect, occurring in about one of every 1,000 live births. The older the mother at the time of conception, the more likely the child will be afflicted. Above the age of 35, pregnant women are routinely offered testing for the Down’s syndrome chromosome.

In 1971, Marilyn Skinner was 26 and not in that higher-risk age group. But when she delivered what would be her only child, Jennifer, doctors noticed the familiar warning signs.

They told the Skinners that their child might be Mongoloid. If true, there was nothing on Earth that could prevent Jenny’s becoming retarded, they said.

Tests would take several weeks. Try not to worry, the doctors said. In those years, the state was willing to take such babies right from the hospital and care for them for the rest of their lives. Parents could walk away as if nothing had happened. Think about it, the doctors said.

But when the news came, sending Jenny away was out of the question, her parents say.

“She was just an easygoing, very loving, very sweet child,” Marilyn Skinner says.

“When you first have a child and they have a handicap or disease or whatever, you go through a period. ‘Why did this happen to me? How am I going to deal with this? Where am I going to get some help? Can I really handle this?’ It’s a normal reaction.

“But when you get past all this, I had a very sweet child who makes friends very easily, who works real hard, does the best she can. She is more than my daughter; she’s my friend.”

Jenny’s mother soon discovered that her baby loved the water.

“If she was in a grumpy mood, I’d put her in water, and she’d be happy as can be,” Marilyn Skinner says.

“I wanted to make her pool-safe, so I started her swimming between 15 and 18 months old. I couldn’t keep her out of it. If she had an opportunity to be in a pool, she was in it.”

This seemed only natural; Marilyn Skinner was herself an athlete and avid swimmer, competing at one time on the Orange Coast College team. She also introduced her daughter to skiing and horseback riding.

*

Her parents soon learned that Jenny could use her mind as well as her muscles. They enrolled her in Montessori schools in Newport Beach and Cypress, “and during that time, she learned a lot,” Marilyn Skinner says.

“She grew a lot. They were very demanding on the quality of her work--one teacher in particular, Judy Patty. She used to hand her homework back and say it was sloppy, do it again. So she did. It was the best thing that ever happened to Jenny.

“People don’t give them credit for what they’re capable of doing. Just like any child, you have to have the desire to help them attain what they are capable of doing. It may take more time, but if you are consistent with your goals, many things can be achieved.”

Other, non-handicapped pupils at Montessori made their mark on Jenny Skinner as well.

“It was they who got Jenny speaking,” says her mother. “As Jenny began to speak more, it was the other students who got excited. They really got along. It was never a ‘you’re handicapped’ situation.

“I think if children can be taught and exposed to all handicaps when they are young, they will be accepting and understanding as they grow up. Not every [Down’s syndrome] person can be in a normal classroom. Some can be for part of the time. But I think the normal population needs to be exposed to them.”

By the time she was 11, Jenny was the oldest pupil in her class, and she was yearning for the company children her own age. Her mother, cheered by her daughter’s athletic ability, wanted a school that offered physical education.

Jenny was enrolled at Hawes Elementary School in Huntington Beach and referred to Cathy Salzman, a specialist in physical education for the handicapped.

Now an administrator in the Tehachapi Unified School District, Salzman remembers Jenny.

“She was just fantastic. What a wonderful, wonderful girl. She had a very positive attitude. She was a hard worker. She didn’t know she had a disability, and that was just fine--not realizing her shortcoming and working with the strengths she had.

“She grew up like a typical child--her education and the way her parents treated her. They treated her like a capable person, and that’s what she was used to. They required a lot of her. They’re loving and sympathetic, but they didn’t let her sit around and do nothing. They didn’t try to shelter her and keep her out of the public and participating with typical children as she was growing up. That’s important. I absolutely agree with that.”

The result, says Salzman, is that “Jenny’s not an extension of the adults around her. She’s her own person with so much personality.”

Under Salzman, Jenny’s athletic career took flight. Salzman’s teams of handicapped pupils from throughout the school district traveled and competed in many sports, mostly as part of Special Olympics.

Salzman “was just a dynamic lady and did every sport in the world,” Marilyn Skinner recalls. “And because she took them everywhere, it was not just a sports program, it was a self-confidence program--taking care of yourself away from your family. She taught them a wide variety of athletic and social skills.”

*

By the time Jenny enrolled at Edison High School, she was competing alongside non-handicapped athletes.

“Marilyn called the [Edison High School] swimming coach, Matt Whitmore, and Jenny swam for him,” recalls Paul Skinner. “He said, ‘Fine, she’s good enough,’ and she swam junior varsity from the first year she was there. He was great to her.

“The other girls treated her fine. She couldn’t interact socially--they were interested in boys and other things--but in the pool they made her feel part of the team. She was part of the team.”

After four years of swimming for Edison, Jenny Skinner joined the Golden West Swim Club, where she and her mother train in the adult program. Last year, when word came that she would be part of California’s delegation to the 1995 Special Olympics Wold Summer Games, Jenny Skinner began to train with more than her usual intensity.

“Oh man, she was flying about three feet off the ground,” Paul Skinner says. “Marilyn and Jenny were swimming three nights a week, trying to get back down to the times she had in high school. It took a year, but she just about got there.”

The Games, held July 1-9 in and around New Haven, Conn., drew an estimated 7,000 athletes from 140 nations.

Sixty-eight came from California, four of them swimmers.

“She’s my strongest swimmer, most definitely,” says Cheryl Poirier, coach for the California swimmers. “She can do all four strokes [freestyle, back, butterfly and breast], which is very unusual for a Special Olympian.”

Jenny Skinner joined her team in Los Angeles and flew east with them, settling in a dormitory at Yale University. There she underwent grueling days--up at 5:30 a.m., in bed by 11 p.m.

It was great, she says.

The preliminary heats for the female swimmers established rankings from which contestants for individuals races were drawn. Swimmers with the best eight times competed in one race, the eight with the next best times in another race, and so forth. Medals were awarded in each race.

Jenny Skinner was in the race for the second-best group of times, swimming all five of her races on the same day.

She won a second-place medal in the 100-meter freestyle, a third-place medal in the 100-meter backstroke and a second-place medal in the 100-meter freestyle relay. She placed fifth in the 50-meter butterfly. (Her 100-meter medley relay team was disqualified when another swimmer began using the wrong stroke.)

To celebrate Jenny’s victories, the family went out for an East Coast lobster dinner.

*

Back home Monday, Jenny added her World Games medals to the collection of medals, trophies and ribbons that virtually cover the walls in her room.

Then it was back to the usual routine.

For mother and father, that means catching up at the small property management company they own and operate in Long Beach.

For Jenny, that means:

* Resuming her Coastline Community College summer school class for job training and getting ready for another semester. Last semester she took courses in critical thinking, consumer skills, reading and writing and health concepts.

* Resuming her list of speaking engagements on behalf of the Special Olympics Athletes Outreach. After discussing topics with her mother, she types out her speeches on her word processor. She is not the slightest bit shy about addressing large audiences, her mother says. She once spoke to a corporate sales conference that filled Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles.

* Resuming her training and competition in dressage, her training for swimming and her wait for snow so she can compete in cross-country skiing once more, where “she gets to go against the guys, and when she beats them she just loves it.”

* Doing almost all the housekeeping for the family. “If she didn’t do what she does at home, we could not go so often to the pool and stables,” her mother says.

*

Ask Jenny Skinner what she wants in the future, and she says she wants to travel.

Her parents, however, are looking further forward.

“She has desires for the future,” says her mother. “She thinks about having her own place to live, talks about having a relationship with someone. Whether that’s just from watching TV, who knows? She has feelings just like anybody else.

“Right now, she doesn’t want to live in a group home. It’s going to be her decision. I hope she’ll find a job at some point that she’ll enjoy, but I’m not going to urge her to accept a job just for a job’s sake. She’s learned a lot in the last two years--bus skills, home skills, life skills. Someday a job will come along that she’ll be excited about.”

If Jenny Skinner ever becomes independent, her mother believes it will be in large part because of her athletic experiences.

“It’s not just an event. It’s training for life, in participation, building friendships--skills in sports but also skills in living. They actually function away from us parents in an independent situation, being places on time, being prepared, getting to bed on time, handling money, knowing how to approach strangers.

“They’re human. They’re capable, not only in sports but in life.”