THE SUNDAY PROFILE : Roads to Riches : Robert Petersen has turned his devotion for cars, guns and motorcycles into magazines --and millions. His advice to others? Be eager and ready to take it in the face once in a while.

- Share via

In a chairman’s aerie aloof above Los Angeles, there’s a shelf with a sentimental spot for a black, cast-iron, upright Underwood typewriter. Its keys are grimy from half a century of fingertips; ribbon dried to brittle, oil to gum. But in its day it smoked. Press releases headed for Hedda Hopper. Biographies of Prince Sua and his Royal Samoans, and stories for the first issue of Hot Rod magazine.

All written by Robert Petersen.

On the same shelf is a photograph of a new building glittering as only Los Angeles does. Searchlights into space. Limo lines streaking reds, ambers, gold lame and chrome bringing the mayor and millionaires to an opening.

Of the Petersen Automotive Museum.

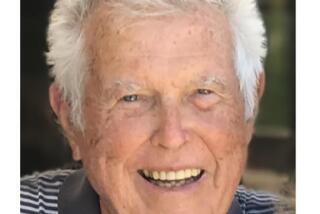

But Robert Einar Petersen, 68, in the withdrawn way he brings to the few interviews he allows, acknowledges nothing unusual in his transition. Sure, he says, it takes luck and timing to ride a beater of a typewriter to a $15-million piece of your own museum in four decades. But nothing really extraordinary.

And this modest millionaire shrugs, looks aside at any suggestion of something inspirational in his biography--a kid from East L.A. who left Barstow Union High School at 15, scraped plates at Henry Wolverton’s Home Cafe for 25 an hour, didn’t go to college but became one of America’s richest men anyway.

“There is a Horatio Alger award, you know, and they once talked to me about that,” he says. “I said no. I don’t believe in these things.”

He also doesn’t believe much in introspection or attempts to intellectualize his successes at publishing, real estate, charter aviation and the toughest slog of all: Life.

“I don’t have any profound messages,” he says. “I think the best thing is to have an eagerness about everything you do . . . always be involved in some new deal.

“And be ready to take it in the face once in a while.”

He confesses no lofty vision, no prefabricated goal to founding and forming Petersen Publishing into a magazine factory of 77 periodicals with 45 million monthly readers. Hot Rod, of course. ‘Teen. Motor Trend. Guns & Ammo. Skin Diver and Sassy. All Petersen publications. All solely owned.

Again the understatement: “About the only secret is catching [a trend] while it’s growing, and get in fast. When it starts slowing, get out. But there’s no magic thing, a lot is guesswork.”

He is quietly satisfied with the $42-million Petersen Building, a 20-story editorial central for the magazines and new to Wilshire Boulevard. And Petersen Aviation, which chartered jets to a campaigning Bill Clinton, a serving Pete Wilson, a trysting Whoopi Goldberg and a fleeing Hugh Grant.

He scuba-dives off Fiji with Cousteau. After Peter Ueberroth insisted, Petersen agreed to be commissioner of shooting events for the 1984 Olympics. He is a denizen of Old Hollywood--long-term friend of Hugh O’Brian and Debbie Reynolds--who threw one of the last free-flowing chili parties closing Chasen’s.

Maybe more remarkable for Petersen’s rich environment and accompanying temptations: He has been married only once, to model Margie McCall for 32 years.

This very ordinary Petersen cherishes 40-year friendships and has a dozen. He talks more about collecting Colt firearms than gathering money. His escapes are wildlife art, fine automobiles, target shooting two-inch groups, and cruising his 65-foot Tollycraft to Avalon.

Also the view from his penthouse office.

Because on a clear day, panning right from the Pacific across the Hollywood sign to East Los Angeles, he sees everything he was.

Over there, on Melrose, was his one-room apartment that trebled as an office and after-work beer joint. The couch made into a bed and he would “get up in the morning, pull the thing up, the secretary would come in and that would be our office.”

See the red billboard? Olympic and La Cienega, site of a second office where Petersen auditioned staff for a motorcycle magazine.

“We’d have them ride around the service station,” he remembers. “If they made two laps, they were hired. Once in a while someone wiped out the pumps.”

There, on Hollywood Boulevard, next to what used to be Grauman’s Chinese. That’s where Petersen opened Hollywood Motorama museum. And on Sunset, the KTLA studios where he helped produce the nation’s first television car program, “featuring Roy Maypole, live from the alley.”

There was no Petersen Publishing in those days, just Hot Rod Inc., which evolved into Motor Trend Inc. Even in those late ‘50s, the magazines were doing well and Petersen’s success earned a visit from his old high school principal, the late Vincent B. Claypool.

“I’ll never forget him,” remembers the publisher. “He stuck out his hand and said: ‘I knew you’d be the No. 1 guy, I always knew you’d make it.’ ”

Petersen ordered Claypool out of his office.

What he had never forgotten was leaving Barstow Union High and hearing Claypool tell final assembly that Bob Petersen was one student least likely to succeed.

*

When beginnings are poor, nomadic and one-parent lonely, there is the easy assumption of an unhappy childhood.

Petersen’s mother died of tuberculosis when he was 10. Dad was a Danish immigrant who fixed DWP trucks and bulldozers building power lines from Boulder Dam to Los Angeles. Young Petersen traveled with the crews and schooling was at any town close to the work camps. Victorville. Baker. Barstow.

“But I didn’t have a bad time of it,” Petersen insists. “I had a good time around nice people. My dad was a good guy, my mom a good guy. You made a scooter out of a box and a roller skate and played a lot of baseball on sandlots.

“I learned about honesty from my father who, if he found a $1 bill in the morning, would spend the rest of the day trying to find the person who lost it.”

Einar Petersen instructed his 10-year-old in welding and decoking engines. Cat skinners and truckers at the camps taught him to shoot, play chess, spin yarns and “the No. 1 code of the camp . . . take care of yourself.”

After his escape from formal education and the dark endorsement of Vincent B. Claypool, Petersen washed dishes, pumped gas, lubed Fords, sprayed water on grocery-store vegetables, and at 16 moved to Los Angeles and the lowest rung of show business.

He was hired as an MGM messenger boy. Pay was $18 a week. The bonus was meeting Clark Gable and Tyrone Power.

“I worked my way up to the publicity clipping room and got to be a planter--planting items with Louella Parsons and Hedda Hopper,” he says. “I’d walk in and say: ‘Hedda, I think this would be a good item. Judy Garland is knitting a sweater out of fluff from her belly button.’

“But I had no idea, no direction, no clear thought of what I wanted to do with the rest of my life.”

World War II looked promising. Particularly if the Air Corps would teach him to fly. But the war was ending, pilot training was slowing, and Petersen had to be satisfied with the photographic portion of photo reconnaissance flying.

“I went back to MGM and began using my military photo training,” he says. “Shooting baby pictures door to door.”

Inconveniently, as Petersen came marching home so did several million other GIs. MGM laid off dispensable employees. Petersen was among furloughed workers who formed Hollywood Publicity Associates.

Hence the Royal Samoans. Then a noisy used-car dealer who cloned a nation of television hucksters: Mad Man Muntz.

Petersen remembers their first campaign: “It was like one of those Mickey Rooney movies. You know, ‘Let’s have a hot rod show, take the money and open the Mad Man Muntz Drag Strip.’ ”

His second idea was a publication to commemorate the event. Petersen knew photography and cars, but nothing about magazine making. A friend didn’t know much about writing, but had access to $400 and his dad published Tailwaggers magazine.

In January, 1948, Hot Rod magazine opened with the car show at the Los Angeles Armory. And Southern California’s growing addiction for converting pre-World War II coupes into smoking hot rods received its first 25 fix.

“We didn’t even have a dictionary,” Petersen says. “But the money came in and it was the only money we had ever seen so, of course, there was a falling out.

“I went on with the magazine and left the hot rod show to Hollywood Publicity Associates.”

Frantic, fun times. Petersen delivered Hot Rod to newsstands on his Harley-Davidson. He pulled in advertising from camshaft and engine builders, and sold the book at the sport’s early temples: Ascot, Gilmore Stadium and El Mirage Dry Lake.

“I’d go through the stands with a change belt and a stack of magazines,” he says. “Then, when the races started, I’d be down on the track to take pictures of the racing with my Speed Graphic.”

He tried widening advertising to oil producers and midget race car builders. They cut him off. To these companies, Hot Rod was synonymous with illegal street racing, police crackdowns and editorial outbursts.

“They said: ‘Change the name of your magazine and we’ll advertise,’ ” Petersen relates. “I said: ‘Hell, no.’ But I did decide to start a magazine for guys more interested in production cars.

“We called it Motor Trend.”

By instinct and gut feeling, Petersen had found a formula: Hot Rod tapped a rich niche, Motor Trend sliced it thinner.

Petersen wondered if there were skinnier niches. Of course there were. Over the decades, Hot Rod spun off Car Craft, Rod and Custom, Chevy High Performance, Custom & Classic Trucks, 4-Wheel & Off-Road and others.

If slicing and dicing worked for cars, continued Petersen’s reasoning, were there millions-in-waiting for magazines rooted in his other devotions? You bet. So along came Motorcyclist (with Dirt Rider and Sport Rider as spinoffs), Guns & Ammo (to whelp Hunting and Handguns), and golf, photography and cycling monthlies that begat annual buyers’ guides.

“You did it slowly,” he explains, “making sure each one had a direction of its own. Then be aware that as it catches, so it comes and goes.”

As citizens band radio and slot car racing came and went. With them, their Petersen publications.

“Off-road is red-hot right now,” Petersen continues. “Mountain bikes are putting more people into ski resorts in summer than skiers in winter. But for how long?”

So no broad topics, nothing prestigious. Just a double whammy giving manufacturers of shotgun speed loaders access to a concentrated, captive audience. While readers curious about development of the ball pivot rocker arm on a GM V-8 have a $3.25 medium for indulging their gluttony.

“Profits,” noted a recent issue of Forbes, “have made Petersen one of the Forbes Four Hundred, worth some $400 million.”

*

A buck saved, Petersen remembers from his six-pack days, is a dollar earned. So his magazines have always been trim, energetic and usually staffed by seven or eight employees. Hires are experts first, writers second and mostly participants in the pursuits they report.

Petersen makes no apologies for the overwhelming male caste of his magazines. Nor for the Barbie doll femininity of ‘Teen and Sassy. He knows that young and male is where the advertising money is.

He’s not concerned by the indestructible sexism of Hot Rod Bikes, where thong bikinis and nubility without tan lines still ride an ’87 Softail. Or the political propriety of his handgun magazines supporting the National Rifle Assn.

He gets letters. A few protests from mothers. But if the Harley swimsuit issue and reporting of Sarah Brady’s income ($110,000 a year) sell magazines, he says, then let’s hear it for freedom of choice and speech.

“I just put out magazines that a lot of people like,” Petersen says. “If there are other people that don’t like them, I guess they should just read something else.

“I don’t get mad at somebody who wants to read the Audubon Society News.”

To those who work for him, have driven against him and hunted Africa alongside him, Petersen is no enigma.

His large skill is for staying surrounded by people of larger talents. If he sometimes seems remote, says friend and car collector Bruce Meyer, president of Geary’s, it is because his mind is several moves ahead of the conversation. Gigi Carleton, his administrative assistant since 1964, says Petersen considers loyalty to a friendship the ultimate morality.

He loves street smarts, the old days, working for no one, Nancy his Irish maid of 30 years, spending the Fourth of July at home, fishing for salmon in British Columbia, the Thalians and other charities dedicated to the young, red wine, red sports cars and his red-haired wife, Margie.

Some say he was tight and self-centered in the early days, which is why he never took his companies public. “Nope,” Petersen says. “I didn’t want anyone else telling me what to do. And when you go public, it’s a big liability against moving fast or doing what you need to do.”

It is suggested that the reduced literary quality of his magazines make them an easy sanctuary for wanna-be writers. Or a farm club for underpaid youngsters on their ascent to serious magazine journalism.

“Am I trying to get classier in any way?” he asks. “No. I think that has killed a lot of people . . . when comedians try to be dramatic actors.

“And I wouldn’t want to be publisher of the New Yorker.”

Critics have long presumed some ego-driven hunt for perpetual identity in the appearance of Petersen on every building, each company and most causes he touches.

He says it has to do with early fumblings among names for his companies. “Then a car-dealer friend came in and said: ‘Why don’t you call your company Petersen Publishing?’

“I thought: ‘Weeeeeellll, maybe I am being a little bashful.’ He said: ‘Look, I’ve been broke two or three times, but right or wrong, I keep coming back and the only thing that did it for me is that I always used my name.’ ”

Petersen is a bear for privacy. His 20-room Beverly Hills Colonial does not have a guest room, but he happily books visiting friends and relatives into the nearby Beverly Hills Hotel. And Petersen is far from self-conscious about his Barstow Union High School education when in the company of other giants.

In his business, he believes, a college degree would have been an impediment.

“It’s a matter of matching yourself with the industry,” he says. “Most of the guys in the [hot rod] industry didn’t like outsiders, didn’t care for people who came in and tried to hotshot it over them.”

They had their ways, their cliques. Today’s legends were yesterday’s grease monkeys pounding out fenders at an Inglewood body shop. Carroll Shelby, racing champion and crafter of the immortal Cobra sports car, started as a chicken farmer.

Says Petersen: “If you walked in on these people and said: ‘Hey, what do you think about this guy who just came out of college and is telling you how to build an engine?’ most of them would laugh.”

*

Not every part of Petersen’s Progress has come up champagne and black ink.

In 1978, with wife Margie as managing director, he bought Scandia restaurant, a Sunset Strip bastion. Despite its gold medals and world-class wine cellar, old customers said Scandia lost its personal touch. Seven years later, the Petersens had it back on the market.

In 1980, they folded Petersen Galleries, a Rodeo Drive outlet for Western, American and early European art. It was killed by a conspiracy and $7 million in purchases of fine art that did not belong to their New England seller, later jailed for fraud.

The lesson, Petersen says, is stick to businesses you know.

Masterpieces. Landmark restaurants. A multimillion-dollar magazine empire. Friends say it is easy to be intimidated by Petersen’s wealth to the point of burying the man’s quieter accomplishments.

“I don’t think people have a clue how influential the guy really is,” says a friend who requested anonymity in exchange for forthright commentary. “Because of his early efforts, we now have the New York and Los Angeles auto shows.

“Without his support there wouldn’t be a National Hot Rod Assn. The Petersen Museum, although only 1 year old, has an international reputation.”

Point at most charities, you will find the Petersens. The Boys’ and Girls’ Club of America. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The Music Center.

Yet, continues the friend, Petersen typically undersells himself. He is not followed by a public relations retinue and accepts attention only as part of a crowd. If he appears self-conscious, even shy, it may be that “the guy is a gentleman in the jungle . . . or at odds with his simple beginnings.”

Robert Gottlieb has known Petersen since they raced hot rods on Sepulveda Boulevard in 1949. Gottlieb turned to law as Petersen entered publishing.

Now he is Petersen’s personal attorney, general counsel for Petersen Publishing and “it has been an exciting, interesting, loving friendship.”

Gottlieb sees his friend as mercurial, generous to the point of being an easy mark, a diverse individual with a killer instinct for making money, and a man intolerant of fools but forgiving of human error.

Car builder Shelby knew Petersen when both were unknown. They shared a love of fast cars and quick romances. Until a double dinner date in New York City ended Petersen’s eligibility.

“I was telling him to treat it like all our other dates, but Pete said no, he was serious about this girl,” remembers Shelby. “He proposed to Margie that first night.

Friends admire Petersen’s dedication to a promise. Earlier this year, he walked carefully into a charity banquet six days after major surgery to mend a hole in his heart. Because, he told worriers, the cause was dear and he had said he would attend.

Above all, those very close respect the courage of Bob and Margie Petersen in recovering from a tragedy that would tear any parent to the soul.

It was the day after Christmas, 1975.

The Petersens and two sons, Bob, 10, and Ritchie, 9, had flown to Colorado, heading for the Little King Ranch, a resort 60 miles northwest of Denver.

The family split between light-plane charters for the final leg; Bob and Margie on one plane, the boys on another.

Bad weather forced the parents’ plane to divert.

The blizzard slammed the second aircraft into the Rocky Mountains. The boys were killed.

It remains something neither discusses easily. If at all. Petersen’s eyes fill when the memories are revived.

“I mean, I was just a very lucky guy up until the time everything bad happened,” he says. “I just had a great situation. And then, one crazy thing.”

He says he grew a bit because of it, started looking and thinking ahead a little more. Good friends helped some. Time did its healing.

Does one recover?

“Nah.”

Yet he came back.

“I don’t know that I’m back,” Petersen says. “But I think Margie and I are very strong and we’re both . . . we’re strong personally . . . yeah, we had each other and she’s terrific. But she was . . . it was bad.”

*

Petersen admits that the day represents a shameless manipulation of the media.

But if the writer thinks a trip to the ranch would build insight, then why not twist the request into a reason for shooting some clays, escaping the office, ducking phones and lunching on salmon, steak and Cabernet Sauvignon alongside Elizabeth Lake?

It is also Petersen’s excuse to play with a new toy--a 1996 Ferrari 355 Spider.

He points the $130,000 convertible toward the high desert northwest of Palmdale and the 3,000-acre Petersen Ranch with its trilevel cabin of peeled logs.

A ground squirrel darts into the road. Petersen jinks to avoid it. The squirrel reverses its scamper. Petersen again yanks the Ferrari away from the animal. This time the squirrel stays still and safe.

“Just shows you,” says Petersen to nobody in particular. “You’d better be sure of yourself. Or don’t do it.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Robert E. Petersen

Age: 68.

Background: Born in East Los Angeles, lives in Beverly Hills; a pioneer of Southern California car culture, owns Petersen Publishing, Petersen Aviation, and is a $15-million benefactor of Petersen Automotive Museum.

Family: Margie, his wife of 32 years.

Passions: Cars, motorcycles, hunting, shooting, fishing, boating and skin-diving. Also cooking, fine wines, wildlife art and wife Margie.

On Margie: “She shares what I do. Not so much that we’re on each other’s necks all day, but enough that when I get home we can have an intelligent skull session and decide how the day went.”

On Storm, his late black Labrador: “I cried my eyes out when he went.”

On millionaires with many and far-flung homes: “We like to be around places that we can use all the time.”

On employees who presented him with a motorcycle to celebrate the 45th anniversary of Hot Rod magazine--then sent it on a promotional tour: “They felt I might get killed if I rode it. Not that they think I am that good, but that the next guy might be worse.”

On owning a Lamborghini that scrapes on his driveway: “We rebuilt the driveway.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.