Cleveland Begins Singing a Different Tune : Cities: After years of hard times, officials are hoping new Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is a symbol of revitalization.

- Share via

CLEVELAND — Its downtown was once so vacant that it seemed an industrial desert, its finances so ruinous that it plunged into default, its river so polluted with flammable chemical sludge that it routinely spewed fire. Now this city is generating a different sort of heat, sparked by the unlikely catalyst of rock ‘n’ roll.

The official opening today of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum has seized Cleveland with the sort of euphoria that greets a World Series victory. Airline flight attendants welcome passengers to “America’s rock ‘n’ roll city” upon arrival. Staid steakhouse waiters are dressing up like rock stars.

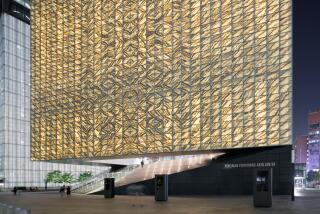

The hall, an angular glass-and-concrete tower designed by renowned architect I.M. Pei, juts out over Lake Erie like a monstrous guitar pick. Instead of the requisite highbrow concert hall or opera house, Cleveland’s leaders have put their faith in a temple of pop culture, hoping it will become as much a symbol of their striving metropolis as the World Trade Center is in New York or the Eiffel Tower is in Paris.

“This city is absolutely on fire,” said David Hoag, chief executive of the steel-making giant LTV Corp., a man not usually given to hyperbole.

If ever a city was on a roll, Cleveland is on one this summer. Construction cranes glide over the skyline, sure signs of a rebuilding boom in full swing. The Indians, the town’s long-dormant baseball team, are leading the American League, selling out every seat at their new stadium. The Cuyahoga River’s fires are a distant memory, replaced by cruise boats and a 1,000-slip marina. For a solid month in midsummer, the city did not register a single murder.

Yet there is unease amid the giddiness, worry that Cleveland’s rebirth will not spread to its poorest neighborhoods, worry that the city has gone too deep into debt, worry even about what kind of place Cleveland is becoming--that the downtown is turning into a playground for suburbanites who may spend their money there but contribute little else to the city’s future.

*

These questions arose even as the city struggled to make the rock ‘n’ roll hall a reality. Music industry figures flirted with Cleveland officials for nearly six years, holding out until the city agreed to front much of the construction cost. With cost overruns swelling the museum’s budget to $92 million, more than half of its funding has been paid by city and county taxpayers whose support has been, at best, grudging.

“If they’re going to be making money off us, they damn well better make sure some of it comes back here,” said Robert Lockwood Jr., a taciturn, white-bearded man of 80 who lives in the Hough, Cleveland’s poor East Side district.

Lockwood speaks from bitter experience. He is a bluesman, one of the unheralded musicians who cobbled the music on display inside the rock ‘n’ roll hall. Lockwood is the stepson of Robert Johnson, the legendary, long-dead Mississippi Delta drifter whose songs of demons, betraying women and aching blues were taken up by rock performers like the Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton and ZZ Top.

Rare 1930s-vintage photographs of Johnson line the display cases inside the hall, along with Janis Joplin’s psychedelic, rainbow-painted Porsche, John Lennon’s “Sgt. Pepper” uniform and Iggy Pop’s duct-taped shorts. Snatches of Johnson’s scratchy, 60-year-old recordings fade in and out amid the throbbing blur of rock, soul, disco, punk, grunge and rap music that swirls from state-of-the-art speakers hidden throughout the hall’s five floors of memorabilia.

*

But there is no mention of Lockwood, an influential musician in his own right. Still smarting after years of exploitation by promoters and record companies, Lockwood angrily spurned a request by the museum to donate a guitar for free. He is planning to sing one of his stepfather’s signature songs, “Rambling on My Mind,” as he rides a float today in a parade celebrating the opening of the hall. But like many in the city’s black community, Lockwood says he wonders if he will be truly welcome inside.

“I guess there’s a lot of excitement downtown,” he said. “I just wonder who’s getting the benefit.”

Critics of the city’s redevelopment strategy say that after 10 years of renewed life downtown, there are few signs of spillover into beaten communities like the Hough. City Councilwoman Fanny Lewis, who has represented the Hough for 15 years, wonders why her constituents have to make do with only 11 police narcotics officers patrolling 50 drug-infested city blocks and why city schools had to be taken over by the state earlier this year--a troubling reminder of Cleveland’s darkest hour, when it went into financial default in 1978.

“Life is good downtown, but it’s like pulling hen’s teeth trying to get money out here for our projects,” Lewis said.

Norman Krumholz, a professor of urban planning at Cleveland State University and the former top Cleveland planning official during its free-fall of the 1970s, said that more than 42% of the city’s residents lived below the poverty line last year and the city is still losing more population and jobs than it gains.

“How many tourist traps can we create in this country before every city is an amusement park?” Krumholz said. “Are we going to have real growth here, with real jobs and business expansion, or are we just standing around with our hands in each other’s pockets?”

The corporate and political leaders who guide Cleveland insist that not only the city’s 500,000 residents, but the entire northern Ohio region stands to gain from the 1 million tourists expected to stream into the rock hall each year. Already, the city’s convention reservations have risen by 50% for next year, city officials report.

Michael R. White, Cleveland’s popular black mayor, says the hall is the city’s “crown jewel,” the centerpiece of a marketing strategy aimed at refashioning Cleveland from its pathetic image as the “Mistake on the Lake”--a local lament about the city’s downward spiral--into the “Comeback City.”

“If a company can reshape its image, so can a city,” White said.

Investing in image can be a dangerous gambit. Detroit tried to recast itself as a “Renaissance City” in the 1970s, banking on the construction of a downtown office and retail complex as the answer to a 30-year flight of businesses and white residents. Today, Detroit’s downtown is a hard urban plain of parking lots and shuttered stores, the legacy of a growth campaign that never took off.

Cleveland’s boosters say there are real gains and real numbers behind their slogans.

There are three new hotels, and White hopes a “convention-sized” fourth hotel will soon join them. The construction of two massive shopping complexes, the Tower City Center and the Galleria, have helped bring 45,000 new jobs downtown since 1978, drawn legions of suburban shoppers and raised land values by 12% during the past three years, said Joe Roman, director of Cleveland Tomorrow, a consortium of the city’s corporate interests. And new apartments and renovated loft units have sprung up by the hundreds along the lakefront--a housing trend that city officials hope could ultimately lure up to 20,000 new residents.

“There’s real excitement to living downtown,” said Cindy Petkac, 28, a planner and resident of suburban Parma who hopes to move into the area’s first new apartment complex built in decades. “There’s Indians games, there are new bars springing up all over the Flats [a riverfront entertainment sector]. And now they’ve got the rock hall. People want to be a part of all that.”

Inside the museum, curators are already juggling an entire schedule of rotating exhibits to make sure “we don’t get stale,” said executive director Dennis Barrie. A veteran of the highbrow art world, Barrie has cultivated a taste for controversy. As the director of Cincinnati’s art museum, he was indicted--and later acquitted--for putting on a display of photographer Robert Mapplethorpe’s erotic portraits.

For the last two years, Barrie oversaw the difficult process of persuading rock artists to give up their own prized mementos so they could be put on display in the hall. Rock stars like Mick Jagger were at first openly contemptuous of the idea, but warmed to it as displays went up.

“Getting this building built gave us the credibility,” Barrie said.

Then the artifacts flooded in: Michael Jackson’s sequined glove--secure under glass. Axl Rose’s kilt. Big Joe Turner’s passport. James Brown lyrics written on Ramada Inn stationery. Run DMC’s laceless Adidas. Twisted chunks of Otis Redding’s crashed airplane. A photograph of Jackie Wilson posing with film director Alfred Hitchcock. And another, of bluesman Robert Johnson, dressed up in a pin-stripe suit in a Memphis, Tenn., studio.

And nothing from Robert Lockwood.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.