Call It Courage

- Share via

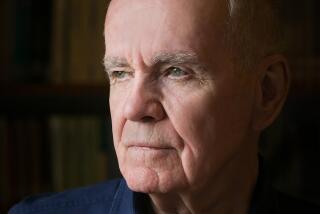

Henry Roth, who died Oct. 13, nearly lost his literary identity six decades earlier in the cross-fire between the Soviet Union and the independent mind.

In 1934, the 28-year-old American radical published his first novel, “Call It Sleep,” and found it praised as “promising” in most newspaper reviews. To Roth’s Marxist friends, however, the novel’s stream-of-consciousness narrative about Jewish immigrant families in New York City was counterrevolutionary and irrelevant. Roth, they said, had compromised his political principles by weaving his childhood memories into the worst kind of prose, the “febrile and introspective novel.” Who cared if the novelist brought the techniques of James Joyce to the insular ghettos of the Lower East Side?

Roth accepted the criticism and returned to his typewriter. This time, he resolved, he would produce something worthy of that “left-wing cultural movement.” He would write a novel about a laborer maimed in an industrial accident, a metaphor for the brutalities of capitalism. But the writer’s heart was not in his work and the manuscript sat lifeless on his desk.

And then, in 1964, a publisher whimsically reissued “Call It Sleep.” Critic Irving Howe remembered the book and took another look. His extraordinary rave appeared on the front page of the New York Times Book Review and the book went on to sell more than a million copies (the hardback first edition had 4,000 buyers). “Call It Sleep” was indeed a great, shamefully neglected work of art.

Still, Roth was to publish no more fiction for another three decades, making such literary mutes as J.D. Salinger and Ralph Ellison seem like mere amateurs. Not until 1994 did St. Martin’s Press issue his second novel, “A Star Shines Over Mt. Morris Park,” the first part of a projected series of books under the umbrella title “Mercy of a Rude Stream.” It was as if the writer had never been away. Once again he resurrected his childhood. Sidewalks and brownstones, parks and public schools rose up once more; people long dead spoke out with the force of youth. Roth’s intense, almost frantic recollection drew its inspiration from Joyce: He had manifestly set out to imitate the Master, with his autobiographical character Ira Stigman playing the part of Stephen Dedalus and New York City taking the place of Dublin.

In the second title in the “Mercy” series, “A Diving Rock on the Hudson” (1995), Ira again serves as Roth’s alter ego, now bewildered by his emergent sexuality, suffering various financial deprivations while his shadowy sister, sensitive mother and brutal father hover in the background. At the core of “A Diving Rock” is a straightforward confessional, as provocative as anything in the chapters of St. Augustine or Rousseau. Ira commits incest with his sister, and he does it more than once.

Those who cannot endure full frontal history argue that Roth’s writer’s block had one cause--the inability to confront this sexual transgression. But Roth’s silence was as much due to political correctness in its original form: to both the Old Left, with its notorious assumption that the difference between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. was merely a matter of initials, and to the right, with its tireless efforts to quash dissent and experiment.

Roth, nevertheless, survived them both. In “A Diving Rock,” he offers us poignant and poetic moments, terror-filled scenes and a story so complex that it had to be accompanied by two family trees and a glossary of Yiddish terms. “From Bondage,” the third installment in the “Mercy” series, will be published next spring by St. Martin’s Press.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.