Tucker Responds Testily to Challenges by Prosecutor : Courts: Under cross-examination at extortion trial, Compton congressman says secretly recorded FBI tapes did not reflect all the conversations he had with informant.

- Share via

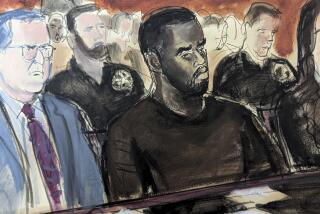

The extortion trial of Rep. Walter R. Tucker III turned testy Thursday as the Democratic congressman faced his first day of cross-examination.

Assistant U.S. Atty. Steven G. Madison, lead prosecutor in the case, took aim at Tucker’s claim that he was working as a consultant when he took $30,000 from a businessman seeking to build a waste conversion plant in Compton.

The government contends that Tucker extorted the money and solicited another $250,000 in bribes from businessman John Macardican while serving as Compton’s mayor in 1991 and 1992.

Macardican was working then as an informant for the FBI in an investigation of official corruption in Compton. He wore a concealed recorder and operated out of an office with hidden cameras.

Replaying portions of one secretly recorded videotape Thursday, the prosecutor pressed Tucker about his failure to object when told by Macardican that the money was in exchange for his vote.

After paying Tucker $2,000 in cash, Macardican is heard on the videotape stating, “That plus the eight [thousand] we agreed on should secure your vote.” The mayor stood up, shook Macardican’s hand and said, “We’ll be friendly, definitely.”

Reminding Tucker that he is an attorney and a former prosecutor, Madison asked: “Is there any reason why you couldn’t have said during this back-room meeting, ‘No, I can’t do that?’ ”

“I could have said a lot of things differently if I had known you all were taping the conversation,” Tucker snapped.

He said he never meant to agree with Macardican’s money-for-votes comment, adding that “it came out of the blue” and “went over my head.” But he said he set Macardican straight as the pair drove to lunch afterward.

The conversation in the car, though not taped, was monitored by two FBI agents who deny the congressman’s account, Madison said.

“Are you saying they’re lying?” he asked. “No,” replied Tucker after a long pause, “they’re mistaken.”

The prosecutor also challenged Tucker’s testimony that he “clarified” his business relationship with Macardican during an impromptu meeting in a parking lot outside the businessman’s Compton office.

During a luncheon meeting May 30, 1991, to discuss Macardican’s project, Tucker had agreed to accept $10,000 in cash from Macardican. The conversation was secretly recorded.

Although Tucker testified that he understood the money was intended for legitimate consulting work, he said he became concerned afterward and sought out Macardican a few weeks later in the parking lot where he “clarified” their relationship.

In his cross-examination Thursday, Madison suggested that the parking lot meeting never occurred.

He asked why Tucker did not telephone Macardican at his office right after their lunch and why he waited two weeks to confront him.

And he challenged Tucker to find any reference to the parking lot meeting in the nearly 30 hours of tapes submitted by the government as evidence in the case.

Tucker replied angrily that he did not make the tapes and contended that they did not reflect all the conversations he and Macardican had during their relationship.

The issue of a consulting arrangement is central to the defense case.

Tucker acknowledges that he received the $30,000 but maintains that $10,000 was a personal loan and the remainder was for advice he gave to Macardican on how to lobby the Compton school district, which owned some land he wanted to buy for the project.

Tucker also contends that the $250,000 fee he solicited from a Macardican associate--actually an undercover FBI agent--was for lobbying the school district on behalf of Macardican.

The government says all the money he solicited and accepted was extorted as a bribe for his votes on the proposal.

Madison also accused Tucker on Thursday of counseling Macardican on how to launder campaign contributions through friends and business associates, a charge Tucker denied.

The prosecutor sought to undermine the defense portrayal of Tucker as a naive and inexperienced politician who was led astray by Macardican, an overzealous undercover operative.

Madison noted that Tucker had worked in the political campaigns of his late father, Walter R. Tucker II, who was elected Compton’s mayor three times. The elder Tucker died in office in 1990; his son succeeded him in a special election.

Tucker’s past also came under fire. In 1986, he was dismissed as a Los Angeles County deputy district attorney for altering a record and lying about it to a judge in a case he was prosecuting.

He pleaded no contest to a reduced misdemeanor charge of altering a public record and was placed on summary probation.

When questioned about his conviction in a preemptive move by the defense, the 38-year-old Tucker characterized it as a “mistake” that he regretted and paid for.

But Madison pressed the defendant about his characterization, declaring that it was not a mistake but rather a willful and intentional crime.

In addition to the allegation involving the waste conversion plant proposal, Tucker is charged with extorting $7,500 from Murcole Disposal, Compton’s residential rubbish hauler, and with failure to pay income taxes on the alleged bribes and other payments.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.