Fury by Birthright : A vicious criminal lives a legacy of violence : ALL GOD’S CHILDREN: The Bosket Family and the American Tradition of Violence, <i> By Fox Butterfield (Knopf: $27.50; 389 pp.)</i>

- Share via

This fascinating book has a story to tell--about Willie James Bosket, “the most violent criminal in New York State history”--and a thesis to offer about the origins of the bloody strain that distinguishes America from less crime-ridden societies. In one sense, Bosket’s story is the perfect illustration of the thesis. In another, it proves only that the mind of any individual human being must remain a mystery.

Fox Butterfield, author of “China: Alive in the Bitter Sea” and member of the New York Times reporting team that published the Pentagon Papers, brought memories of his own childhood in the segregated South to bear on his interviews with Bosket, a double murderer by age 15 who is serving three 25-year-to-life sentences under New York’s version of the “three strikes” law.

Violence in the United States is not “a recent problem or a particularly urban bane,” Butterfield argues, “and in its inception had little to do with race or class, with poverty or education, with television or the fractured family. . . . Rather, it grew out of a proud culture that flourished in the antebellum rural South, a tradition shaped by whites long before it was adopted and recast by some blacks in reaction to their plight.”

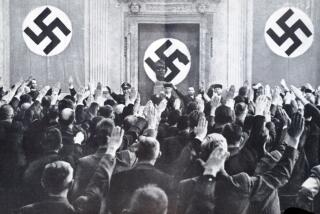

And if Southern violence, linked to a hair-trigger sense of “honor,” had a focal point, he says, it was “bloody Edgefield,” a region of South Carolina settled by touchy, belligerent Scotch-Irish, ravaged by guerrilla war between revolutionaries and Tories, brutalized by slavery and famous for its upper-class duels and lower-class brawls.

This was Klan country. Edgefield’s roster of political firebrands runs from secessionist Gov. Francis Pickens (who owned one of Bosket’s ancestors) to Gov. “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman to Sen. Strom Thurmond.

In the 1890s, as Southern whites insisted that upholding their honor justified violent acts (such as lynchings) above and beyond even Jim Crow laws, a new breed of “black badmen” arose willing to act outside the law in the interests of “reputation” or “respect.”

One of these was Bosket’s great-grandfather, Pud, who tore the whip away from a white landowner who had ritually beaten his sharecroppers at the start of each planting season. That was heroism, but Pud’s later efforts to establish himself as the baddest man around set a dubious precedent for his son, James, who also had a criminal record.

The Boskets moved to Augusta, Ga., and to New York, hoping to escape but finding that the culture of violence moved with them. It was outside, on the mean streets, and inside, in the Bosket men’s paranoiac rages and the Bosket women’s tradition of negligent parenting.

James’ son, Butch, was first institutionalized at age 9 after his mother dressed him in his best suit, gave him a quarter, put him on the subway and told him to get lost. He killed two men in Milwaukee, became the first U.S. prison inmate to become a Phi Beta Kappa, won his release after “superhuman efforts” at rehabilitation, molested his girlfriend’s daughter and died in a shootout with police in 1985.

Butch’s son, Willie, inherited his father’s intelligence and charm--and, in his mother’s perhaps self-fulfilling conviction, a propensity for evil. He, too, was in custody at age 9. “No reformatory or mental institution could hold him for long,” Butterfield says. “He assaulted his social workers with scissors and metal chairs, set other inmates on fire. . . . Psychiatrists prescribed antipsychotic drugs; they had no effect.”

When Willie was arrested for murder in 1978, he claimed to have “committed 2,000 crimes, including 200 armed robberies and 25 stabbings.” In 1988, he gravely wounded a prison guard with a “shank,” or homemade knife. His isolation cell is lined with Plexiglas to keep him from throwing excrement at his keepers. He calls himself “a monster created by the system” and given a “license to kill” because he can receive no harsher punishment.

Willie Bosket is ideal for Butterfield’s purposes because his family’s criminal history springs so clearly from Edgefield and slavery; less than ideal because a person so extreme and singular can’t be explained in any terms except his own.

“All God’s Children” comes up with some striking statistics on murder rates to show that “the South, not the Wild West, as popularly believed”--or the industrial North--”was the most violent region of the United States” in the 19th century.

But Butterfield’s theory that present-day urban gang members’ lethal reaction to being “dissed” echoes that of hot-blooded slave owners bred in the tradition of “seven centuries of fighting between the kings of England and Scotland” takes a bit of stretching to apply to California, where the racial mix is wider and the origins of violence surely more various.

Bosket is a more potent symbol of another trend: America’s return to punitiveness after a long period of reform that had gradually made treatment of criminals more humane.

At the model Wiltwyck School for Boys (which Willie’s father, Butch, had attended before him), the idealistic staff abandoned its no-drugs policy in Willie’s case because he couldn’t be controlled without them. Shocked by the “baby-faced killer’s” initial five-year sentence, the state of New York in 1978 passed the “Willie Bosket law” allowing murder suspects as young as 13 to be tried as adults. Other states followed suit.

“This was not a small matter,” Butterfield says. “The new law represented a sharp reversal of 150 years of American history . . . the first break with the progressive tradition of treating children separately from adults. It also marked a departure from the cherished American ideal of rehabilitation--the notion that kids could be changed and saved.”

Could Butch and Willie have been saved? The saddest parts of the book are the failed attempts, not just by bureaucrats and cops but by caring and gifted educators who had succeeded with youths just a little less volatile.

In the end, the Willie Boskets have beaten the system. Not knowing how to civilize them, we have let them coarsen us. Racism contributes: “Most white Americans instinctively see violence as a black problem,” Butterfield says, though “there is good evidence that . . . there is little difference in crime rates between whites and blacks.”

Modest measures that might help--and Butterfield suggests a few--get little support in an era of massive prison-building. “If more prisons was the sole solution . . . we should be among the safest nations on Earth.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.