On the Union Front : Look at Walter Reuther gives insight into the evolution and decline of American labor and liberalism : THE MOST DANGEROUS MAN IN DETROIT: Walter Reuther and the Fate of American Labor, <i> By Nelson Lichtenstein (Basic Books: $35; 592 pp.)</i>

- Share via

On a spring day in 1937, wearing a suit and vest with a watch chain, Walter P. Reuther walked to the top of an overpass that led into the Ford Motor Co.’s massive River Rouge auto plant near Detroit. Its 80,000 workers lived under a regime of ruthless foremen, informal cliques (from Masons to pro-Nazi Silver Shirts) and the notorious Ford secret police and spies known as the Service Department.

Despite this intimidating atmosphere, a few left-wing union organizers had persuaded thousands of Ford workers to join the United Auto Workers. Reuther, the leader of an aggressive, fast-growing Detroit local union, had recently helped conduct the great sit-down strike in Flint, Mich. That strike had forced the world’s biggest corporation, General Motors, to recognize the UAW and inspired tens of thousands of workers to form unions.

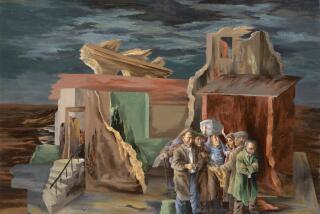

Thirty-year-old Reuther, then only one of several young leaders on the rise, decided that the UAW needed to establish a physical presence at River Rouge by publicly leafleting the workers. With witnesses and journalists in tow as they climbed the overpass, Reuther and three colleagues were suddenly surrounded by 40 men, who pummeled them bloody and kicked them down the stairs. One photographer escaped with dramatic photos, images of what historian Nelson Lichtenstein describes as “labor-capital conflict in its most violent and direct form.” The “Battle of the Overpass” was a disaster for Ford but catapulted Reuther to public prominence that lasted a lifetime.

Reuther was not simply one of the most important and widely recognized labor leaders in American history; he was also a key figure in shaping--for both better and worse--mid-century political liberalism. Lichtenstein, who teaches at the University of Virginia, has produced a compelling, meticulously researched biography of Reuther. Sympathetic, yet bluntly critical at key points, Lichtenstein’s portrait goes beyond biography to offer keen insights into the evolution and more recent decline of both American labor and liberalism. This is a very public biography with little attention given to Reuther’s psyche or personal affairs, in part because Reuther’s ascetic, disciplined life really was the union.

Born into an immigrant German socialist’s family of five children, two of whom--Victor and Roy--were also influential figures in UAW history, Walter Reuther grew up immersed in family dinner-table debates on issues of the day. Though entranced from an early age by skilled craftsmanship, he became a lifelong enthusiast of industrial mass production. During the auto boom of 1927, Reuther left his home in West Virginia and quickly found work in Detroit--eventually at Ford’s River Rouge plant--as a skilled toolmaker, the proletarian elite.

The Depression suddenly gave new relevance to his father’s socialism. In 1932, Reuther left Ford and, with Victor, toured a Europe facing fascist threats before spending nearly two years as craftsmen at the Gorky Auto Works in the Soviet Union. Reuther was appalled by the chaos he witnessed but in both letters and later speeches praised Soviet ambitions.

Soon after he returned to Detroit in 1935, he married May Wolf, another energetic young Socialist Party member, became leader of a union local, and led his first strike. The New Deal was in full flower and shaped Reuther’s lifelong politics. According to Lichtenstein, he emphasized two linked but sometimes clashing goals: “industrial democracy in the shop and mass purchasing power in the paycheck.”

At first Reuther worked closely with militants, including communists, and attacked red-baiting, which was often directed against him because of his Soviet trip. Vibrant debates and ideological faction fights filled the UAW’s first tumultuous decade, and Lichtenstein’s careful account reveals all major protagonists--communists and non-communists--as acting out of varied mixtures of principle and narrow ambition or deviousness.

Reuther was often lambasted as an opportunist, first by fellow socialists for working with communists, then by former allies for crudely exploiting anti-communism to consolidate power. After he narrowly won the presidency in 1946, Reuther’s drive for control suppressed some of the union’s rowdy but vital democracy. His crusade ultimately weakened the union, Lichtenstein contends, and Reuther soon discovered that the union’s greatest threat came from the right, not the left.

As a leader, Reuther was more willing than restive shop radicals to compromise with corporations to secure limited, interim victories. He hoped both to tap and to discipline rank-and-file combativeness. But by 1940 he had moved away from “factory centered militancy” to a greater reliance on the government as a counterbalance to corporate power.

During World War II, Reuther enthusiastically embraced the “‘corporatist” idea of labor, management and government cooperating to maximize war production. But business leaders rejected any tinkering with hallowed “managerial prerogatives.” Also, while both executives and communists urged discipline, wartime workers repeatedly broke the union’s no-strike pledge with wildcat strikes, often over workloads. Reuther tried to tiptoe an unsatisfactory middle path through this minefield.

After World War II Reuther championed vigorous government action to maintain full employment and expanded tripartite cooperation. He would have liked American liberalism to resemble Swedish-style social democracy, but the public mood turned more conservative and less sympathetic to unions.

Reuther’s political judgments in the postwar years were deeply influenced by his ever-closer ties to the Democratic party. Though he was a strong and early supporter of the civil rights movement, challenging racist elements of his own union, he often opposed black insurgencies--such as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party--that threatened the Democratic establishment. (He also ranged from slow and inept to unsympathetic and repressive in dealing with demands of black UAW members for more power in the union.) Later, even as his colleagues and their children turned against the Vietnam War, he defended Lyndon Johnson and the war, while carefully avoiding the extreme hawkishness of his archrival, AFL-CIO President George Meany.

Lichtenstein views Reuther’s life from the 1950s on as a “tragedy” of a man imprisoned “first by the poisoned legacy of an obsessive anti-communism, then by an alliance with an unreformed Democratic Party and finally by the transformation and demobilization of the UAW itself.”

Reuther died in a plane crash in 1970 on a visit to the nearly completed worker education center he had built at Black Lake in Michigan. At that point the decline of organized labor over the next quarter century was only dimly foreshadowed. But the recent election of a new, more militant AFL-CIO president, John Sweeney, may represent Reuther’s revenge against the legacy of his nemesis, Meany.

Now in many ways the balance of power between workers and employers in the United States is returning to what it was before the Battle of the Overpass. New strategies will be needed if labor is to revive itself, as well as new Reuthers, though many of his ideas--such as global unionism--remain vital. In any case, as Lichtenstein writes, one thing has not changed: “From his earliest days . . . Reuther emphasized that a sense of justice and solidarity underlies the very essence of the union idea.” Whatever his limits, that passion clearly governed Walter Reuther.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.