‘Balto’ Depicts Real-Life Heroics

- Share via

The Times recently published a letter claiming that the “true story” upon which the Amblin-Universal movie “Balto” was based was itself a fabrication created by the serum supplier as a “publicity stunt” (“A Different ‘True’ Story of ‘Balto,’ ” Calendar, Jan. 6). The facts state otherwise.

The Associated Press covered the diphtheria epidemic in Nome, Alaska, and the various attempts to speed antitoxin to its citizens from the day the story broke on Jan. 28, 1925, to the arrival of the dog-sled team under “Balto” and musher Gunnar Kaasen on Feb. 3. The Times need not have gone any further than the AP archives to realize how serious the situation actually was. The following is a telegraphed appeal from Nome dated Jan. 30, 1925, when it appeared the dog-team would arrive long after the available coffin supply had been exhausted:

“Help immediately. Help by airplane with antitoxin serum, in the appeal of Nome, not for the Sourdoughs but especially for the children, the young Americans of tomorrow. We do not want to ask Soviet Russia to send an ice-breaker with antitoxin, nor do we ask that the Shenandoah or Los Angeles be dispatched, but please get Uncle Sam to send an airplane from Fairbanks with two red-blooded men, who have volunteered to fly to Nome in four hours’ time in order to bring relief.”

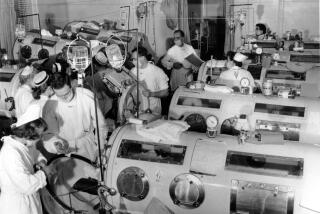

Unfortunately, an airlift from Fairbanks was impossible and as the dog-team relay was underway from the railhead at Nenana, the situation in Nome worsened. The letter in Calendar claims that vaccine promoters were embarrassed at the arrival of the antitoxin, yet the mayor of Nome, George S. Maynard, had convened a special health board, closed the schools and “engaged at public expense all the available nurses” to aid Dr. Curtis Welch, Nome’s sole doctor, in controlling the outbreak. Nome was quarantined. The Associated Press report from Jan. 31, 1925, under the heading “Epidemic Is Taking Lives,” shows what happened before the antitoxin arrived:

“Five persons have died from diphtheria, 22 cases have been reported, 30 persons are suspected of having the disease and 50 others have come in contact with diphtheria patients during the epidemic raging here. . . .”

The dog-sled team arriving on Feb. 2 brought with it 300,000 units of diphtheria antitoxin from what could be spared of existing stocks in Anchorage. The “manufacturer” was uninvolved and would stand to gain nothing whatsoever from any “publicity stunt.” The Calendar letter claims that the vaccine was faulty, yet it was merely frozen during its 674-mile trip from Nenana and perfectly usable once thawed. What the letter-writer describes as a “publicity stunt” at one time or another had the involvement of the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Surgeon General, the U.S. Department of Public Health, the U.S. Department of Justice, congressman for Alaska Dan Sutherland and 20 mushers driving more than 100 dogs.

It’s easy to nit-pick the Universal film “Balto” for its departure from the confines of history, but the movie serves to put the spotlight on the “indomitable spirit of the sled-dogs”; a spirit that enabled diphtheria antitoxin to complete a 20-day journey in just over five--still considered a record today.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.